Anatomical dissection is a matter of course for today’s medical student. Those who selflessly donate their bodies to science are treated with utmost respect for the critical service that they provide to burgeoning doctors and surgeons. Medical schools in the 19th century had a more difficult time with this aspect of education and often had to turn to “anatomical men” or “resurrectionists” to procure cadavers for study by their students. Virginia schools had no legal means of acquiring bodies until 1884 when legislation established the state anatomical board and made the bodies of prisoners and the indigent available for study. An August article in Style Weekly piqued the interest of some Library of Virginia (LVA) archivists, which turned up some interesting archival records about Richmond’s own “anatomical man,” Chris Baker.

Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) professor Shawn Utsey has endeavored to uncover the thus-far unknown history of Baker’s work for the Medical College of Virginia (MCV). In that effort, he has combed the archives of MCV and the LVA as well as other sources. So far revealed is that from sometime after the Civil War until just after World War I, Baker worked as a janitor in MCV’s Egyptian Building. However, his duties went far beyond the tidying of the dissection room. With the tacit approval of the college, Baker and his cohorts (often including young medical students) trolled African American cemeteries, the Alms House, and other locales of the poor and anonymous to procure the newly deceased for study. For this service, MCV paid Baker up to $10 per body, depending on condition.

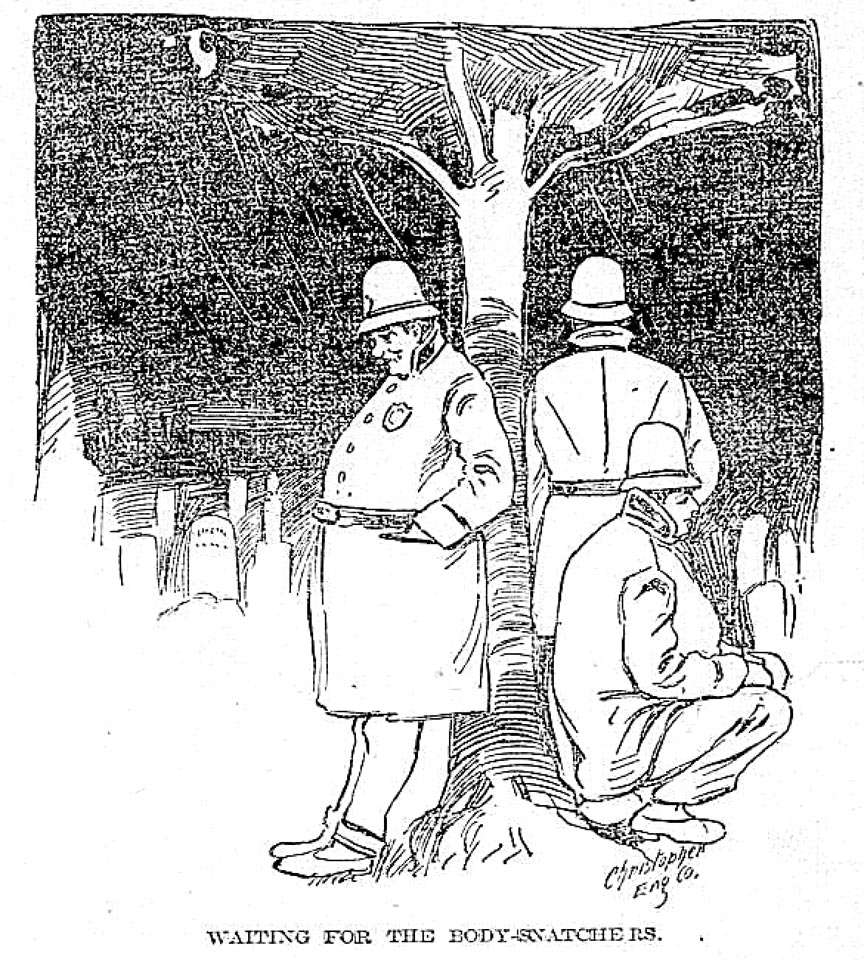

In December of both 1882 and 1883, Baker and others were arrested for disinterring corpses. The Richmond City Ended Causes, in the Local Government Records collection at the Library of Virginia, contain the indictments from 1882 for offenses at Oakwood and Sycamore cemeteries. Illustrating the unspoken approval of officials, Baker and his companions were convicted in Richmond court on 20 December 1882 and pardoned by Governor William Cameron the next day, a speedy exoneration indeed. In addition to the local court records and state pardon papers, numerous newspaper articles on Baker and body-snatching can be found in the Richmond newspapers of the period. Several relevant titles are part of the Library’s Virginia Chronicle database, which can be searched by keyword or phrase.

It is unclear whether Baker was a freedman or a slave owned by MCV. Some records indicate that his parents also worked at the college, but again it is unclear whether they were enslaved or free. In a strikingly similar case described in Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training (1998), the Medical College of Georgia purchased a slave named Grandison Harris to procure their bodies for dissection. Like Baker, Harris was somewhat respected by the white population, especially the medical community, but reviled by African Americans. In Richmond, the latter group looked upon Baker as a ghoul for his nocturnal activities. So much an outcast, Baker considered himself a prisoner of the Egyptian Building, fearing reprisal if he ventured too far beyond its environs.

Dr. Utsey’s efforts to uncover Chris Baker’s story will culminate in a documentary film in the near future. In addition to discovering revealing records in the archives, Utsey has interviewed several Richmond residents who recall being told cautionary tales about “Old Chris” and what would happen if he caught you out after dark.

The General Assembly enacted legislation in 1884 creating the state anatomical board and empowering it to procure bodies for dissection from the penitentiary, county jails and alms houses, and other public institutions holding corpses to be buried at government expense. Despite this new legal source of cadavers, Chris Baker was again thrust into the spotlight when MCV took possession of the body of executed prisoner Solomon Marable. The 1 August 1896 issue of The Richmond Planet recounts the efforts of a group of angry citizens, including publisher John Mitchell Jr., to reclaim the body, which had been transported to the college and packed in a barrel of salt for preservation. Included in the article are sketches made by Mitchell of the scenes that the group encountered that night.

Chris Baker’s clandestine labors, considered ghastly by our modern-day sensibilities, provided a valuable service to the medical profession. A formidable character, Baker was said to have ruled the dissection room and possessed considerable knowledge of human anatomy. One professor even referred to MCV in a 1898 newspaper article as “Chris Baker’s College.” Though his macabre errands required him to creep through the inky, gas-lit night of 19th century Richmond, shovel and bag in hand, the archival collections of the capital city have shed new light on Richmond’s “resurrectionist.”

-Vince Brooks, Senior Local Records Archivist

To whom it may concern,

I found your article tonight and could not sleep without atleast trying to ask about my family member.

My GGrandmother, died in Pulaski Co., VA. in abt 1907. It was passed down through the family that her husband, against his family’s wishes, donated her body to science in Richmond. I’ve never located a death record for her, through the State or County, and there are no burial records for her. Is it possible that the Medical College of Virginia or the Library of Virginia kept a record of her death or any record of my GGrandfather donating her body for science? By the way, my father also donated his body to science at MCV at his death in 1983. Would there be a record of him?

Thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to ask my queston. I just never thought of contacting MCV.

My GGrandmother was, Nancy Jane Dobbins Dickerson, died abt Jan 1907, in Pulaski Co., VA. My Father was James Jesse Brown, died 14 Oct 1983 in Richmond VA.

Best Regard,

Jessie Clarkson in Oklahoma

Jessie Clarkson,

Thanks so much for your question. We do not have the records of the State Anatomical Board, a possible source for answers, and I do not know where those records reside or if they still survive. It would be worthwhile to ask our reference archives desk your question about death records here at the LVA. The e-mail address is archdesk@lva.virginia.gov You should also ask your entire question of MCV. A logical starting place would be the Special Collections and Archives, Tompkins-McCaw Library, Virginia Commonwealth University. The general e-mail address there is libtmlsca@vcu.edu Best of luck in your search and thanks for reading the blog!

-Dale Dulaney

Archival Assistant

The Library of Virginia