While processing some City of Richmond court records from the Civil War era, I came across the remarkable narrative of a mother named Martha Hobson. A search of Richmond newspapers on Virginia Chronicle and additional city records revealed more about her experience. It is appropriate to share Martha’s story during Mother’s Day week.

Martha Ann Hobson was born enslaved in the early 1820s. We do not know the name of the person who first enslaved her. At some point, she became enslaved to a free African American man named Richard C. Hobson. They lived together as husband and wife and around 1840, they had a son named Robert C. Hobson. Richard emancipated his wife and son in a deed recorded on 8 July 1850 in the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond. Soon after her emancipation, Martha registered as a “free black,” and the Hustings Court granted her permission to remain in the commonwealth.

Over the course of the 1850s, Martha’s husband used the income he earned as barber to acquire property in Richmond. According to the 1860 census, Richard Hobson held real estate valued at $3,300, which equals nearly $100,000 in today’s dollars. The Hobsons lived in the Second Ward (east of 22nd Street) of Richmond where their neighbors were lawyers, merchants, underwriters, and the city sheriff, all of whom were white.

Around 1860, anticipating the limited educational opportunities for their son in Virginia, the Hobsons used their accumulated wealth to send Robert to Boston to attend school. After a few years, Martha wanted to go to Massachusetts to visit him, as any mother would. However, it was now 1862 and the nation was in the midst of the Civil War. Travel by land or sea was nearly impossible, and so the Hobsons turned to the Confederate government for assistance. On 9 September 1862, they submitted an application to Confederate officials for a passport to allow Martha to go to Massachusetts and return to Virginia. Approval of such a request also involved negotiating an agreement with the Union army to permit her to cross enemy lines, twice. Remarkably, Confederate General John H. Winder, the provost marshal of Richmond and the man responsible for managing the capital city, approved the passport for Martha Hobson.

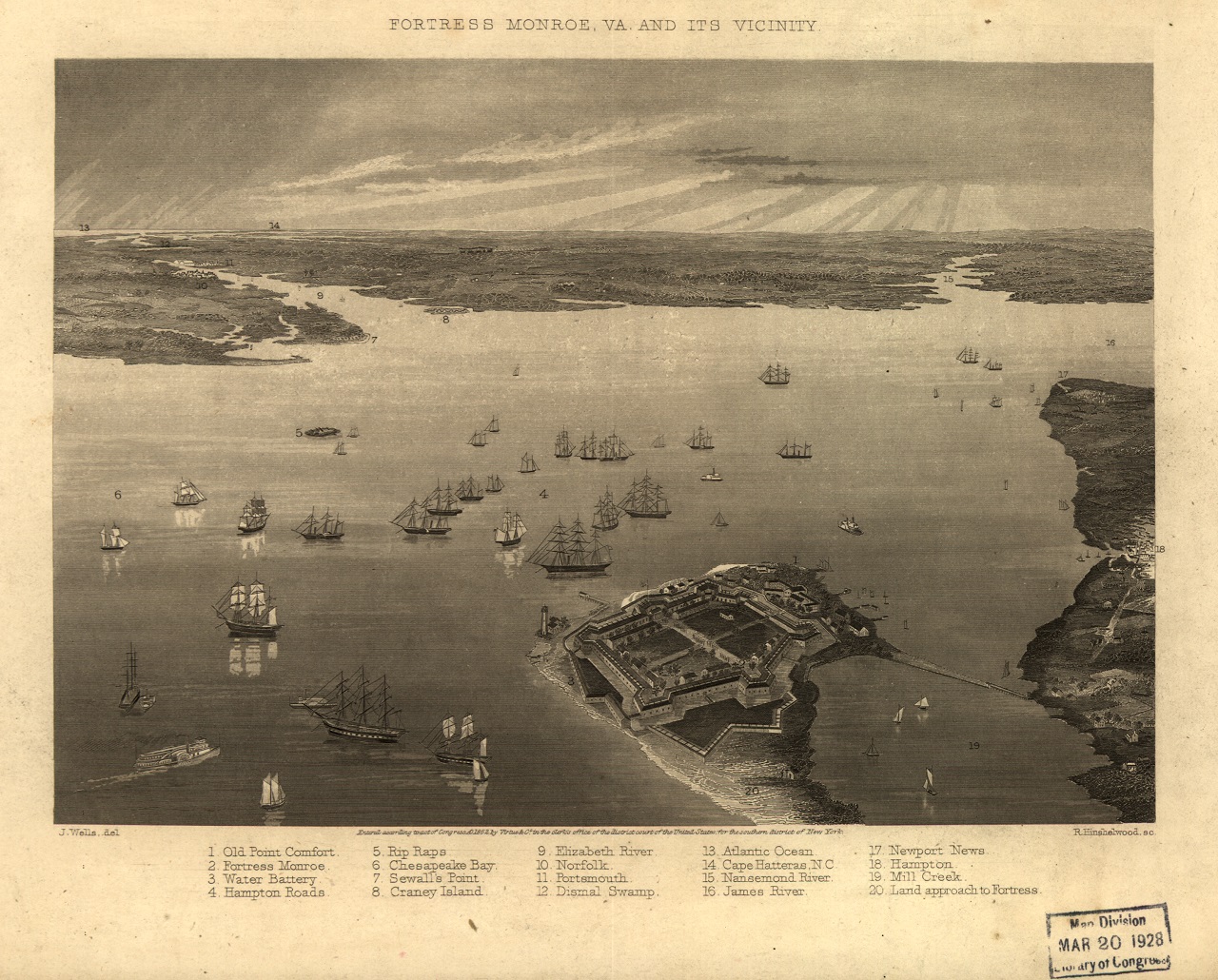

Martha traveled to Aiken’s Landing on the James River near Varina, where Union and Confederate forces regularly exchanged prisoners. She sailed on a Union boat under a flag of truce to Fortress Monroe in Hampton Roads, then under the control of the Federal Army. From there, she traveled to Massachusetts to visit her son. After an unknown period, Martha returned to Virginia, again under a flag of truce, arriving at City Point. There she met Confederate government official Robert Ould, the man responsible for prisoner exchanges. He permitted Martha to reenter the Confederate States and return to her home in Richmond.

There she remained peaceably until August 1863 when Joseph Mayo, the mayor of Richmond, learned of Martha’s trip to and from Massachusetts and ordered her arrest. Martha came before the Mayor’s Court where Mayo charged her with breaking a law passed by the General Assembly in 1857. That law made it illegal for free people of color to travel to a free state then return to Virginia. Mayor Mayo found Martha guilty, ordered that she pay the person who apprehended her one dollar and that she leave Virginia within ten days and never return. If Martha refused to comply with his judgment, she would receive twenty lashes across her back as punishment.

Martha and her husband immediately filed an appeal to the Richmond Hustings Court, which stayed Mayo’s sentence until the appeal’s hearing. Martha’s case went back and forth between the Hustings Court and the Mayor’s Court during the autumn of 1863. During that time, Richard Hobson reached out to the Confederate government to provide his wife with a passport to Massachusetts where she could remain with their son. This time, they refused the request. A reporter covering the trial for the Richmond Daily Dispatch acknowledged Martha’s plight. “To obey the orders of the Court … she must run the blockade – a feat not easily accomplished.”

As Richard Hobson frantically searched for a way for his wife to leave the commonwealth, Martha’s lawyer, John Howard, worked the courts to prevent her public whipping. He provided the court with several reasons why Martha Hobson was not guilty of any crime and had been “illegally & extrajudicially condemned to a severe and ignominious punishment.” The bulk of Howard’s defense rested on his contention that neither the Mayor’s Court nor the Hustings Court had any jurisdiction over the matter of Martha leaving and returning to Virginia. Under the Confederate constitution, the regulation of all intercourse with foreign nations rested solely with the Confederate States government. Howard argued that Martha left Virginia and returned under the authority of the Confederate government “of which the State of Virginia forms partes [sic] she is amenable to no other authority.” In other words, Confederate laws or regulations superseded any conflicting state law, even if that law was part of the state’s constitution.

In a response to Howard’s argument, Joseph Mayo said the 1857 state law had not “been repealed by the Legislature, which body can alone make or repeal laws.” He then proceeded to use the same states’ rights argument against the Confederate government that secessionists used against the United States prior to the Civil War: “I have yet to learn, that there is any Confederate authority in this Commonwealth that can by repeal, or otherwise abrogate any constitutional law of Virginia.”

The Hustings Court sided with Joseph Mayo. On 5 December 1863, it dismissed the rule that had delayed Martha’s lashing should she refuse to leave the state in ten days. Mayo declared his intention to whip Martha Hobson out of the commonwealth. On day nine, Martha filed an application to the Hustings Court for permission to remain in the Commonwealth. The court agreed to hear application—the following week. The court did not explicitly state whether her punishment would be delayed until it heard her application. Unfortunately, the records are silent on whether Mayo carried out her punishment or if Martha found a way through the blockade and left Virginia. According to the 1870 census, Martha and her husband Richard resided in Richmond along with their son Robert and his wife.

In 1872, an event occurred in Richmond that must have astonished Martha given her experience a decade earlier. Her son Robert led a parade of United States Colored Troops veterans, known as the Attucks Guard, through Richmond in celebration of George Washington’s birthday. At noon, Robert led the Attucks Guard to City Hall to greet Mayor A. M. Kelley. Unlike Mayor Mayo, who expressed contempt for Robert’s mother, Mayor Kelley publicly praised Robert and the members of the Attucks Guard for being “worthy soldiers.” Robert thanked the Mayor and the people of Richmond for their kindness. I would like to believe a mother was in the crowd watching with a heart full of pride for her son.

Martha Hobson’s astonishing story is one of many narratives of African Americans available on Virginia Untold. The scanning, indexing, and transcription of the records found on Virginia Untold were funded by Dominion Resources and the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) administered by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Virginia Chronicle is a historical archive of Virginia newspapers, providing free access to full text searching and digitized images of over a million newspaper pages made possible by funding from multiple National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) grants.

–Greg Crawford, Local Records Program Manager