One of the little things that anyone born in the last 60 years has come to take for granted is the ease and convenience of making a photocopy. Photocopy machines have become so ubiquitous since the early 1960s, they spawned a brand-new verb: “Xeroxing.” Before the advent of the photocopier, making multiple copies of a document was a bit more complicated. Of course, you could always handwrite a duplicate copy, but, hey, what are we 15th-century monks?

The Library of Virginia holds a couple of artifacts from circuit court clerks’ offices that illustrate two early copying methods utilized in those offices. By comparison, they’ll surely make us appreciate the luxury of our pocket computer-cameras and recognize how far we’ve come.

Edison Mimeograph Machine

Thomas Edison received the patent for “Autographic Printing” in August 1876 (U.S. Patent 180,857). A second patent four years later (U.S. Patent 224,665) concerned making the stencil using a metal stylus. Albert Blake (A.B.) Dick, a Chicago-area lumber businessman, licensed the patents in 1887 as part of his effort to move into the business machine market. Dick is credited with coining the term “mimeograph” by combining the Greek word mimỏs (imitation) and graph (to scratch). His business machine company, later known as ABDick, would be an industry leader through the late 20th century.

The user would scratch the text, using a metal stylus, into a waxed sheet (either mulberry paper or, later, nitrocellulose). Akin to screen printing, a roller was then inked and rolled over the stencil page creating a second copy. Both nitrocellulose and benzine, which was used to clean the equipment, were highly flammable, so smoking while mimeographing was not advised!

This Edison Mimeograph Model No. 1 by the A. B. Dick Company was purchased by the Chesterfield County Circuit Court Clerk’s office around 1890. It retailed for $15 (about $530 in 2024 dollars) and may have been used for producing copies of notices or other documents made in multiples. The kit still contains filled ink tubes, stylus, roller, and (empty) solvent bottles.

Elliott & Hatch Book Typewriter

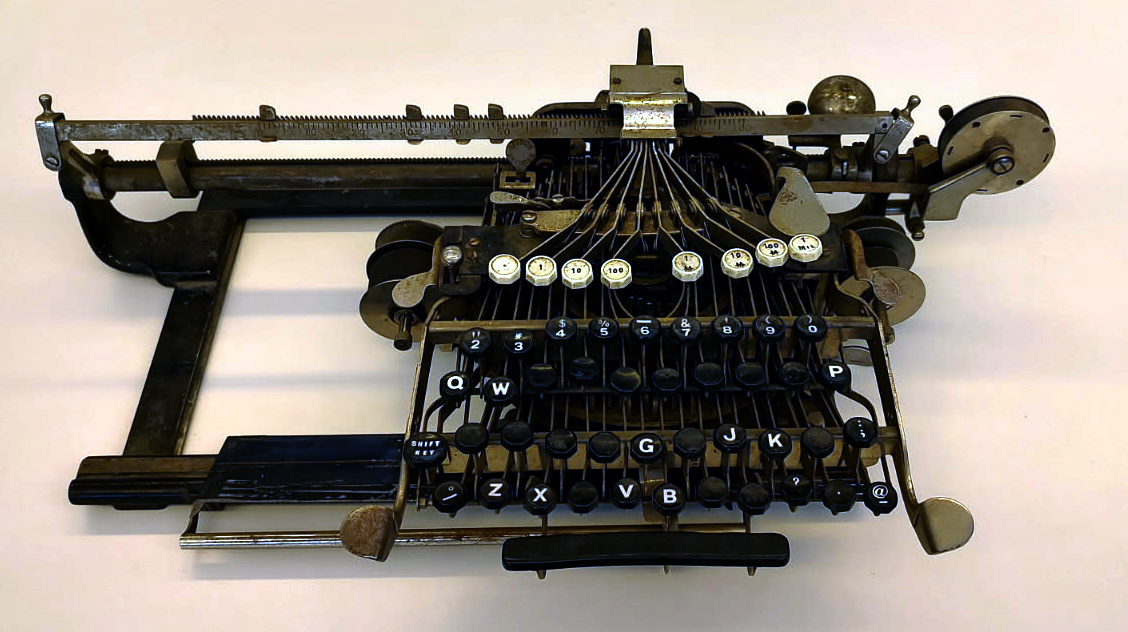

In 1996, a very unique-looking typewriter was transferred to the Library along with Accomack County court records. The machine is an Elliott & Hatch book typewriter from around 1900.

Elliott & Hatch formed sometime in the 1890s and very quickly marketed themselves across the nation, especially to local governments. The Chronicling America newspaper database returned articles indicating purchases of Elliott & Hatch book typewriters by government officials in Ohio, Iowa, Connecticut, Kentucky, Colorado, and other states.

The Elliott & Hatch machine could type horizontally, making it useful for record volumes such as deed and will books maintained by circuit court clerks. At the turn of the 20th century, the device cost between $175 and $200 (about $6,702 in 2024 dollars), so it was quite an investment.

In fairly short order, the Elliott & Hatch Company found themselves embroiled in controversy. Allegations of inducements to officials and other shady dealings began to surface. In 1901, the New-York Tribune told the tale of a “mysterious typewriter bill” for machines Elliott & Hatch book typewriters “furnished to the city in 1898 under most peculiar circumstances.” The invoice was for a whopping $22,000!

A couple of years later, in 1903, two men were indicted for their roles in a scheme to sell Elliott & Hatch book typewriters to postmasters across the country, whether they requisitioned them or not. George W. Beavers (head of the Postal Service’s salaries and allowance division) conspired with H. J. Gensler (a U.S. Senate stenographer and sales representative for Elliott & Hatch in Maryland, Virginia, and D.C.), and W. Scott Towers (superintendent of Station C of the Washington Post Office) to take $75 from every $200 sale as a kickback. Between 1898 and 1901, Gensler sold the USPS 193 machines for a total of $38,575 (approximately $1.47 million in 2024 dollars). Towers and Beavers were indicted in D.C. in October 1903.

The USPS scandal articles describe the Elliott & Hatch book typewriters as “not a success” and as “useless and an incumbrance” to postal staff. Despite these critiques and several lawsuits involving patent disputes, the company merged with the Fisher Book Typewriter Company in 1903 to form Elliott-Fisher. That firm acquired the Underwood Typewriter Company after World War I and, in 1927, became Underwood-Elliott-Fisher. Eventually, it became the Underwood Corporation (circa 1930), a name beloved by typewriter enthusiasts today.

Other technologies existed for reproduction but nothing compares to the ease of what we have today. So, the next time you get frustrated with your phone taking a blurry image or the Xerox machine jamming, take a moment to appreciate the fact that you don’t have to ink a roller, potentially explode when cleaning it, or horizontally type with an inferior contraption.