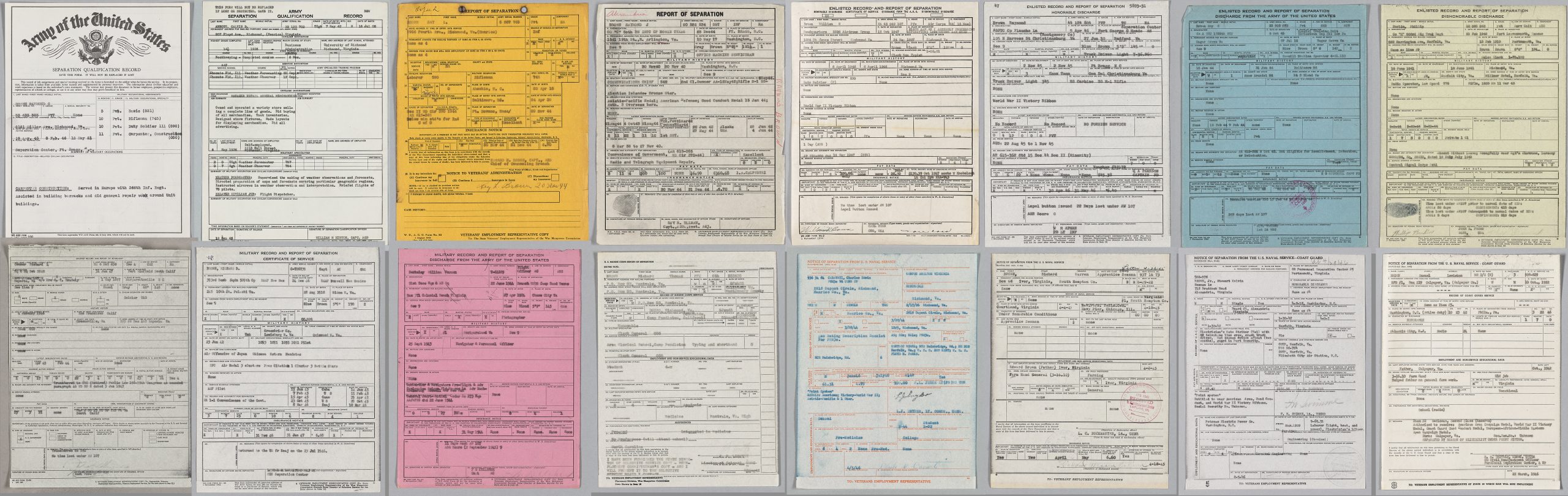

My internship is with the Digital Initiatives & Web Presence division of the Library of Virginia, a department responsible for the Library’s digital collections and web projects. I specifically work with the collection of World War II Separation Notices, consisting of approximately 270,000 separation records of those having served in World War II. The bulk of my work consists of organizing the metadata – the digital files that exist now that the thousands of papers have been scanned and uploaded onto the server – and ensuring that items like soldier’s names, identification numbers, and cities are properly transcribed so that they can be searchable by the public. I also am lucky enough to help with the digitization lab, combing through items in the library’s stacks and public floors for media like microfilm, blueprints, and historical documents to digitize. Digitizing these documents is important for public access, with uses ranging from raising public awareness to student research to genealogy.

As a student of Middle Eastern studies and advocate of devoting research into one’s heritage for the sake of collective memory and personal exploration, I was determined to find a way to make this internship about 1940s American soldiers… connect with me, a Middle Eastern American 20-something-year-old woman who admittedly doesn’t know much about the military.

Interning with Digital Collections

From my first day of working with the separation notices, I made it known to my supervisor, Lauren, that my personal goal is to find immigrant stories, preferably of people of color, in these records. We both knew that not only would it be a difficult find but it would stick out like a sore thumb. Amidst a sea of thousands of American names, not as many as I expected would be classified as Black (“Negro” in the documents), only a couple handfuls would be listed as female, and 2 in 3,500 would be a blatantly “foreign” name.

As of the time I am writing this, five weeks into my ten-week internship, I have gone through approximately 3,600 soldiers’ files and found two names that I confirmed were either immigrants or children of immigrants. I unfortunately won’t be getting into the story of one of the two names, Carlos Roesler Bell of Brazil.

The second family name is what led me to my research here today: Boyajian. The suffix of -ian immediately gave away that this was likely a name of Armenian origin, and a quick search proved this correct. Brothers Noober George Boyajian and Sam Boyajian were born in Richmond, Virginia, to parents of Armenian origin, and fought in the U.S. Army during World War II. Their separation notices revealed some background information, such as their birth years being only a few years apart, their addresses being the same household, and their documented race matching one another’s, but not matching their last name. Of the limited categories available, “White/Negro/Other,” the Boyajians were classified as “White” by the census even if other Americans might not have seen them that way.

In this post, I will be exploring the history and nuances of Middle Eastern/Armenian migration to the United States that led to families like Boyajian in Richmond.

Immigration or Servitude?

Middle Eastern and North African immigration to the Americas can be traced back to the 16th century, with Moroccan Estebanico Azemmour (enslaved by the Spanish at the time) being a part of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition to the Gulf of Mexico in 1528.1 Azemmour was one of four survivors of the expedition, significant as one of the first Arabic-speakers in the Americas. In 1619, records reveal an individual with Middle Eastern roots in America, with a John Martin the Armenian, or John Martin the Persian, from Isfahan among the first in Jamestown. British State Colonial Papers and the Court Book of the Virginia Company of London reveal that Martin came from London as Virginia colonial Governor George Yeardley’s servant, then becoming a tobacco farmer after Yeardley’s death.2 Two more Armenians are documented as having been brought from Turkey afterwards to introduce silk production. However, these (specifically the Armenians), are isolated immigrants (or rather, servants who were then able to benefit via assimilation and settler-colonialism), and it wasn’t until two centuries later that groups from the region began immigrating to America.

The late 1800s saw the start of Middle Eastern migration to America, with most coming from the Ottoman Empire’s Greater Syria: present-day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. A combination of escaping politics, economic crises, and religious persecution led to this migration. Immigrants found work predominantly in the Northeast and Midwest,3 until the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 severely limited the number of immigrants allowed to enter the country, favoring those of Western Europe and explicitly excluding those from Asia.4 This saw a drop in Middle Eastern immigrants until some exceptions were made to the law after World War II.5

How Armenians Arrived in Richmond

”The burden of deciding where to go was placed on young Manuel Vranian who was the best schooled of the group. His elders set down certain requisites; they wanted a location south of New York with more temperate weather, but not too distant to make the cost of travel prohibitive. In later years Manuel Vranian explained it this way: "I took a map of the United States. There was a large area south of New York but the name "Virginia" appealed to me. So I chose Richmond since it was the capital and the largest city in the state."

Kaye Brinkley Spalding"Immigrants in Richmond, Virginia: Lebanese, Armenians and Greeks, 1900-1925" (Master’s Theses, University of Richmond, 1983).

Preceding the Johnson-Reed Act there was a peak of another ethnic group of the Ottoman region finding itself in the U.S.: the Armenians. Initially immigrants in search of opportunity (many of whom came at the hands of Protestant missionaries), the Armenian population in the U.S. consisted of refugees from massacres like the Hamidian and Adana in the 1890s-1920s. The Armenian Genocide saw Turks of the Ottoman Empire kill up to 1.5 million Armenians by its end in the 1920s, leading to even more of the population being displaced. Approximately 54,000 Armenians immigrated to America between 1899 and 1917, many of whom travelled to the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic (New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Pennsylvania), Midwest (Illinois, Michigan), and West (California).6 However, Armenians also found themselves in cities like Richmond, Virginia.

| Ward | Lee | Madison | Jefferson | Clay |

| Total Population | 49,081 | 40,758 | 41,946 | 39,882 |

| Black | 20,601 (41.97%) | 15,097 (37.04%) | 13,009 (31.01%) | 5,334 (13.37%) |

| Foreign-Born White | 1,305

(2.66%) |

1,194 (2.93%) | 1,107 (2.64%) | 1,031 (2.59%) |

1911 Redistricting: Numbers show that each ward in Richmond in 1911 had over 30%-40% black and foreign-born white populations, besides Clay with a total of about 15%.

In 1911, four wards existed in Richmond after the gerrymandering of Jackson Ward: Lee, Madison, Jefferson, and Clay. Each ward had between 39,000 and 49,000 residents, with approximately 1,000 being foreign-born whites from each. Immigrants like Lebanese, Armenians, and Greeks settled from the Ottoman Empire to Richmond, in no particular ward. While some wards were more popular among each group, (Jefferson for the Lebanese, Lee and Madison for the Armenians, and Madison for the Greeks), assimilation seemed to have taken precedence over building ethnic community quarters.

Many of Richmond’s Armenians of the early 20th century found themselves settling here from New York via train, often living near lower Main Street as the train station was there. A 1910 U.S. Census survey showed that most of the Armenians in Richmond were mostly unmarried young men, 35% of which were skilled workers, with a majority of them literate. After World War I, however, the population varied with mainly women (52%) and children (21%). This is likely due to the fact that after 1909, most of the Armenians coming to Richmond were orphans brought by relatives here, including some to be married. Armenian children attended Richmond Public Schools and learned Armenian at home until a school was established in the 1930s. Meanwhile, an Armenian church was not established until 1956, unlike Lebanese and Greek churches.7

By 1920, about 30% of Armenians in Richmond owned real property, likely with help from Richmond Syrians, one of which was married to a Richmond Armenian. This connection led to financial stability in the community, in which many Armenians worked occupations such as confectioners, barbers, grocers, and fruit salesmen, with women often assisting in family stores.

Middle Eastern Americans in WWII

By World War II, about 13% of the U.S. military was comprised of ethnic minorities, the majority consisting of African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese Americans, Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, and Puerto Ricans.8 About 30,000 soldiers are estimated to have been Arab American, while about 18,500 were Armenian.9 Largely unable to serve during World War I because they were “ineligible” due to Turkish citizenship, Armenian Americans played a significant role in World War II and were awarded medals, like Richmonder Ernest Dervishian’s Medal of Honor.10

Armenian American soldiers also held a unique point of view during the war: often the offspring of survivors of genocide, they saw fellow Armenians as prisoners and slave laborers in Germany.11 This drew a connection between what the previous generation of Armenians endured during World War I and the same ideology affecting them in World War II.

Citizenship and Racial Classification of Armenian Americans

1909 saw Ottoman-born Armenians in America being granted citizenship for the first time, namely in a successful attempt at proximity to whiteness. Caught in the blurred definition of the “yellow race,” it often took court hearings with attempts at stretching the boundaries of whiteness to justify citizenship for Armenians.

Navigating and expanding the law held significant power over the status of early Middle Eastern immigrants in America – similar to the status of early freed Black Americans, albeit with the advantage of being able to fall under the definition of white for the former. However, this did not prove to be advantageous when navigating social status: Armenians remained outcasts, often referred to as “dirty black Armenians” or “low-class Jews.”12 The nuances of racial classification of the Middle Eastern and North African diaspora in America today are rooted in these early court cases. The American dilemma of identifying whiteness remains, with this diaspora in particular still being categorized as white today – affecting prospects for resources and benefits for a minority community.

Why Research This?

The story behind how families like the Boyajians originated in America is not just a preview into the hidden stories of American war history, but also part of the narrative of migration, U.S. racial categories, and survival. These glimpses into the stories of and laws against early immigrants can inform prevalent issues regarding immigration and xenophobia. This history reveals how communities like the Armenians and others of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region were blended into America’s story, usually without public knowledge. Researching these names and lives reveals the gaps in our history and reminds us of the responsibility we have to be fully informed of the past that once again repeats itself.

This blog post is dedicated to my fellow Middle Eastern Richmonders, a population I grew up thinking consisted of me and only me but now find ever-growing as a result of displacement – rooted in colonization and dictatorships, greed and borders. A population I find mild comfort in no longer feeling alone in, but more so heartbroken over the evils that have led us so far from our homelands. This research provides evidence that displacement of those of the “third world” is far from a 21st-century problem, and (unfortunately) something that can connect both old and new communities in America today. From the Indigenous who have been here for tens of thousands of years (yet are now displaced on their own land), to the African Americans forced here for hundreds, to the Latin Americans and Middle Easterners recently seeking refuge, and many more. I hope we can continue to leverage our similarities to advocate for the rights of all oppressed people, while simultaneously learning from and engaging with our differences.

Footnotes

[1]“Early Arab American Collections: Early Arab Communities in the United States,” New York Public Library, last updated Feb 3, 2025, https://libguides.nypl.org/c.php?g=1387989&p=10277963.

[2] Robert Mirak,“Torn Between Two Lands: Armenians in America,” Hadjin, last updated September 15, 2011, http://www.hadjin.com/TORN_BETWEEN_TWO_LANDS_Armenians_in_America.htm.

[3]Raymond Habiby, “Middle Easterners,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, last updated August 15, 2024, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=MI007.

[4] “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations: The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act),” Office of the Historian, accessed August 8, 2025, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act.

[5] Becky Little, “Arab Immigration to the United States: Timeline,” History.com, last updated May 28, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/arab-american-immigration-timeline.

[6] M. Vartan Malcom, The Armenians in America (The Pilgrim Press, 1919), retrieved from https://archive.org/details/cu31924032752200.

[7] Kaye Brinkley Spalding, “Immigrants in Richmond, Virginia: Lebanese, Armenians and Greeks, 1900-1925” (Master’s Theses, University of Richmond, 1983), https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1032.

[8] “Minority Groups in World War II,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed August 8, 2025, https://history.army.mil/Research/Reference-Topics/Minority-Groups-in-World-War-II/.

[9] James H. Tashjian, The Armenian American in World War II (Boston: Harenik Association, 1952).

[10] G. W. Poindexter and John G. Deal, “Ernest Herbert Dervishian (1916–1984),” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia, 2016, http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Dervishian_Ernest_Herbert.

[11] Gregory Aftandilian, “Armenian-American Soldiers as Liberators Against Nazism,” International Journal of Armenian Genocide Studies 10, no 1 (2025): 1-17, https://doi.org/10.51442/ijags.0062.

[12] Aram Ghoogasian, “How Armenian-Americans Became ‘White:’ A Brief History,” Ajam Media Collective, August 29, 2017, https://ajammc.com/2017/08/29/armenian-whiteness-america/.