Editors Note: This post originally appeared in the former “Virginiana” section of Virginia Memory.

When we think of Capitol Square, it conjures up visions of Thomas Jefferson’s venerable Capitol on the hill, Alexander Parris’s elegant Executive Mansion, and Arthur S. Brockenbrough’s public privy. Well, maybe not the latter, but to the ordinary visitor of Capitol Square in the early nineteenth century it was equally important.

The early part of the nineteenth century saw the most significant amount of change to Capitol Square since its formation in the 1780s. In 1816, French architect Maximilian Godefroy was appointed to draw up a plan for the improvement of the “Public Square,” as it was often called. Since Godefroy’s plans do not survive, it is not known whether he first suggested a public privy on the Square. Governor James P. Preston, however, began granting various contracts based on Godefroy’s plan which included landscaping, a cast iron enclosure, a stable, and a public privy. Construction began on the privy, or necessary, in September 1818, when Arthur S. Brockenbrough, Superintendent of the Improvement of the Public Square, contracted William G. Goodson to complete the carpenter’s work and furnish the materials necessary for its construction. Located, appropriately, next to the newly constructed governor’s stable, the public privy was built a few hundred feet south of the Executive Mansion on the southeast corner of Capitol Square close to James Warrell’s museum. Brockenbrough certified that the work was completed on 25 October 1818, entitling Goodson to a payment of $225.

The following year, Brockenbrough wrote Governor Preston “estimating the probable cost of conveying the water under the public privy to carry off the filth from it.” In his letter, Brockenbrough enclosed his plan to construct a system of culverts running from Capitol Street on the northern edge of Capitol Square to Bank Street passing under the privy. Brockenbrough’s map stands as the only known record of the location of the privy. Despite Brockenbrough’s system of culverts, the Public Privy became more of a public nuisance according to the various overseers of Capitol Square. Adjutant General Claiborne W. Gooch reported to Governor Thomas W. Randolph in August 1820 on the need to purchase three casks of lime to throw into the privy stating that it was “absolutely necessary to the health of the citizens in its vicinity.”

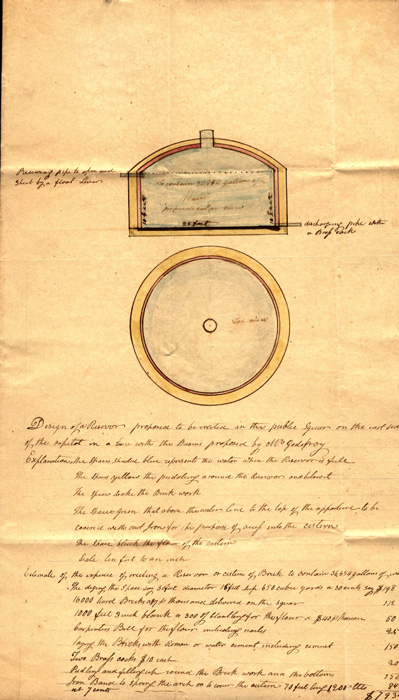

Captain Blair Bolling, Commandant of the Public Guard, assumed the duties of the privy as Superintendent of Public Edifices by an Act of the General Assembly passed in 1821. As Commandant of the Public Guard, Bolling repeatedly wrote the governor on the wretched state of the privy. He suggested conducting water from the spring on Capitol Square to the privy using wooden pipes at a cost of twenty-five cents per foot to keep water moving through the culverts. In his letter of 1 August 1826, Bolling wrote of the need to repair or replace the same pipes from the fountain between the Bell House and Capitol which served to convey water to a reservoir under the public privy and from a culvert into the James River. Shortly thereafter, Bolling noted that no water was flowing from the hydrant on the east side of the Capitol to the privy due to the deterioration of the pipes.

In March 1827, the old pipes were dug up on the Square and replaced with newly constructed iron pipes. In addition, a reservoir was built on the east side of the Capitol which, according to Bolling, would “remove the intolerable nuisance which has been annoying the citizens in the neighborhood of the Museum.” In May 1828, Bolling asked that the line of iron pipes be extended from the hydrant east of the Capitol to the public privy. Later, Bolling asked for an iron circulator at the hydrant to force water through the iron pipes to the privy. Bolling enclosed an estimate of repairs to the privy by Bosher & Brown in November 1830, which included seven new seats and seven bars above the seats “as to compel the person using it to sit down.” Bolling went so far as to propose alterations to Bosher’s plan for the privy seats to “prevent the filthy practice of getting upon the seats with the feet.”

Constant problems of cleanliness, disrepair, and particularly vandalism beset Captain Bolling and caused the ultimate demise of the public privy. In March 1828, Bolling wrote, “rude boys collect there, and…break and destroy everything about it and actually wage war against the person employed to keep it in order.” Bolling later declared:

“I am entirely at a loss to know what will be best to be done to prevent the abuse of that establishment for the fact that there are persons who frequent it who behave more like brutes than men and appear to put themselves to great trouble to destroy, or render the place unfit for the purpose intended.”

To combat the problem, Bolling suggested a locked iron gate for the privy with a key for each of the public offices at the Capitol. To the dismay of Captain Bolling, an act of the General Assembly provided another entrance into Capitol Square near the museum, prompting Bolling to suggest a lattice frame to conceal the privy. He amusingly wrote in May 1836 that since the opening of the new entrance, the privy had become “a place of common resort for persons of all descriptions whose olfactory nerves are capable of sustaining the shock.” In the same letter, Bolling reiterated his appeal for a lock and keys to the public officers at the Capitol.

Captain Bolling finally succumbed to his battle against the public privy upon his death in 1839. Bolling’s second-in-command, Lieutenant Elijah Brown, took up the fight recommending to Governor David Campbell its closing based on the fact that it was no longer used by the public officers of the Capitol. John B. Richardson, Bolling’s eventual successor as Superintendent of Public Edifices, too recommended the closing of the privy, despite another round of repairs, a lock, and a sign reading “Closed until the next meeting of the General Assembly.” Finally, on 28 October 1839, the Council of State advised Richardson to nail up the privy.

-Craig S. Moore, State Records Appraisal Archivist

(From the VA-Roots Listserv)

Your post intrigued me, especially the reference to a museum owned by James Warrell.

It makes you wonder if any of the exhibits remain, transferred to a currently existing facility. It sounds as if the Warrell-Lorton museum was practically next to the privy. No wonder ticket sales declined if it took all that legislstion and repair to keep the water flowing under the necessary. It looks to me like the museum was located where the parking lot for the Capitol Police now sits. I wonder where the refuse outlet to the James was? Probably just before the lock to the east on Canal St. – Must have been a real tourist attraction in the summer!

Thank you for some very entertaining posts.

According to the apocryphal grapevine (next to the apocryphal privy) Mann Valentine II got lots of pieces in his collection from the old Capitol Square Museum. Samuel Mordecai I think wrote about one exhibit which was a live snake. It met its demise when the prey they fed it bit the snake – who saw that coming- thus ended that exhibit.