Editors Note: This post is a modified version of an article that originally appeared in the former “Virginiana” section of Virginia Memory.

The following story was gleaned from a case book found in the Western State Hospital collection (Accession 41404). Included in this volume are approximately twenty pages of physician’s entries, as well as a copy of the commitment order, a letter to the court, and several Richmond Dispatch newspaper articles relating to Mrs. Anne E. Kirby. Some of the dates and information are conflicting, but I have done my best to present the story as accurately as possible, well aware of the sometimes questionable nature of 19th century journalism and the possibility of human error within the case book entries.

NOVEMBER 21, 1865…

A shot rings out in the middle of a bustling crowd at Richmond’s Second Market. A fish and oyster vendor staggers through Pink Alley, bleeding from the neck, only to die minutes later in the back of a wagon. Several stunned witnesses pounce on the shooter. Holding the gun is the victim’s young wife, Anne, the mother of his three children. What might have driven her to commit such a bold act in a busy public place? Was the murder in retaliation for her husband’s infidelity or was it merely the work of a mad woman? Depending upon what one believes, it may have been a little bit of both.

THE YEARS BEFORE…

Anne Collins’ life in the Richmond area began innocuously enough. She was born the child of Irish and English immigrants who arrived in Virginia when she was a young child. She was commonly educated and as a teenager found work as a nurse in the home of Reverend Dr. More. It was while employed by the Mores that Anne (also known as Annie) met a man named Robert Kirby. Mr. Kirby was older and already married to his second wife when he seduced and carried on an illicit relationship with Annie Collins. Annie was very young, naive, and in love with the older man. After realizing Robert had no intention of leaving his wife, Annie swallowed what she thought to be a lethal dose of laudanum (tincture of opium), a common sleep aid; she survived. When the overdose failed to get the attention she desired from Mr. Kirby, Annie climbed onto the Petersburg Railroad bridge over the James River, intending to jump. She was prevented from doing so and her suicidal episodes were written off as evidence of juvenile jealousy of Mr. Kirby’s marriage. Eventually though, after divorcing his wife, Robert Kirby married Annie Collins on December 19, 1861.

THE DAYS BEFORE…

By 1865 Mr. Kirby was a moderately well-known seafood vendor and barroom owner and his wife, an industrious twenty-one-year-old mother of three. By all accounts, they lived an average existence in the neighborhood of Broad and Seventh Streets. However, their short marriage had been a tumultuous one. Annie accused Mr. Kirby of physically abusing her. She also complained that Robert ignored her and their children in favor of other women. According to her neighbors, Mrs. Kirby regularly trolled the streets in search of her missing husband. During one search she arrived at the bakery owned by Mr. Augustus Liebhauser. There she was informed that Mrs. Liebhauser was not at home. The news threw Annie into a jealous rage as she assumed her husband was in the company of the baker’s wife. Mr. Kirby stayed out all night, reportedly because he was afraid Annie would kill him if he went home.

MURDER AT THE SECOND MARKET…

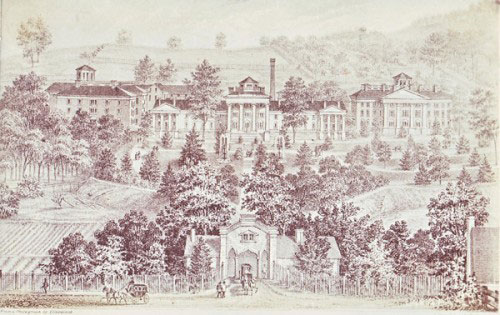

Between seven and eight o’clock on the morning of November 21, 1865, Mrs. Kirby arrived at her husband’s stall in the Second Market, located at the intersection of Sixth and Marshall Streets. She screamed at Mr. Kirby, scratched his face, and threw a chair at him. According to witness testimony, Annie abused her husband for some time before Mrs. Liebhauser opened the window to the nearby bakery. The baker’s wife peered out and made a gesture toward Annie—one witness attested that she put her thumb to her nose and twirled her fingers—which further enraged Mrs. Kirby. In the heat of the moment, Annie pulled out a pocket pistol and aimed it at Mrs. Liebhauser. She quickly turned to Mr. Kirby and exclaimed “I’ll shoot you, you son of a bitch!” Annie fired three shots, one of which struck her husband in the neck, severing an artery. Robert Kirby stumbled through the market and died in the back of a wagon. Annie Kirby was quickly overpowered by several witnesses and immediately taken to jail. Her case was eventually heard in Richmond’s Hustings Court, during which several doctors gave opinions of Mrs. Kirby’s level of sanity. Some believed she was completely insane and therefore not responsible for her actions. However, others suggested that Annie might be a “simulator,” faking her insanity to avoid punishment. The judge was not entirely swayed by either diagnosis. In early February 1866, upon a petition of the defense, the judge ordered Annie committed to Western Lunatic Asylum in Staunton. It was left to Dr. Francis T. Stribling, superintendent, to determine the true condition of Mrs. Kirby’s mind.

INSANITY OR SIMULATION?

Annie Kirby arrived at the asylum on February 6, 1866. Due to the notoriety of the case, Dr. Stribling took great care in monitoring and describing Annie’s actions during her stay. In the beginning, Dr. Stribling was convinced Annie was pretending to be insane. He and his staff played tricks on her, such as “accidentally” leaving a vial of laudanum, which actually contained a harmless substance, in her room to see if she would make another suicide attempt. She did not. (Annie later ingested the “laudanum” when it was offered by a nurse. However, she denied doing so upon the realization that the substance had not delivered the desired effect). The doctors and attendants also deliberately made remarks, within Mrs. Kirby’s earshot, about their belief that she was simulating. In one conversation, the attending physician remarked that Annie did not constantly move her hands as “real” lunatics were supposedly known to do. They hoped to trick Annie into proving her insanity, but she did not fall for their attempts at entrapment. Mrs. Kirby’s case record reveals that her behavior while committed was sometimes rational, but at other times completely nonsensical. Sometimes she admitted to being insane, agreed that she had killed her husband, and understood that she would face a murder charge if brought back to Richmond. At other times during her stay at the asylum she had to be force-fed, refused to dress herself, and did not pay attention “to the calls of nature.” She babbled incessantly about mermaids and singing trees and refused to believe Mr. Kirby had died at all, let alone by her hand. Needless to say, Mrs. Kirby’s psychological condition was not easily diagnosed and thus she remained a patient at Western Lunatic Asylum for more than a year.

THE PROGNOSIS…

In an August 1866 letter addressed to the court, Dr. Stribling wrote that in the beginning he believed Annie to be a simulator, as her “motive to feign was powerful.” Although she did have a motive, the doctor reported that Mrs. Kirby did not act on remarks that were designed to entrap her. Dr. Stribling pronounced her insane, as well as suicidal, and suggested that Annie required continued treatment at a lunatic asylum. On the surface it was a succinct diagnosis. However, the letter contained one very curious statement that cast a small shadow of doubt over his claims. Here Dr. Stribling admitted that Annie had indeed simulated while at the hospital, “probably believing herself not insane, and having a motive, she has attempted to place the mask of insanity over a mind already unsound.” Was Annie a crazy woman pretending to be a sane one, who was in turn pretending to be insane? Or was she merely skilled at confusing doctors? As Annie quietly settled into life at the asylum, the entries in her case book became less-detailed and more infrequent. The physicians considered the cessation of Annie’s erratic behavior as a sign that her insanity was cured. On May 9, 1867, Annie Kirby, who only months before was considered hopelessly insane, was released from Western Lunatic Asylum as “recovered.”

THE TRIAL & A SURPRISE…

After arriving back home, Mrs. Kirby was held in Richmond City jail to await trial. She spent little more than two months behind bars before she was released on bond due to an illness. The trial finally began during the first week of October 1867, nearly two years after Mr. Kirby’s death. The Richmond Dispatch covered the event in great detail. According to the reporter, several witnesses called attention to Mr. Kirby’s licentious behavior. Miss Adaline Jane (colored) and Mr. William L. Rose both claimed that Mr. Kirby and Mrs. Liebhauser were “criminally intimate,” and had been seen frequenting Vine’s assignation house, the modern day equivalent of a rent-by-the-hour motel. Mr. H.C. Rogers claimed that Robert Kirby was “just a man of that sort,” who ran around with other women. However, others testified that Mrs. Kirby had on several occasions publicly “abused” her husband. Mr. John Gentry testified that Annie had gone as far as to admit to him that she planned to shoot Mr. Kirby. Mrs. Kirby pled not guilty to the charge of first degree murder. No insanity defense was invoked because Annie chose to rely solely on the evidence of her husband’s brutality. On October 5, 1867, Annie E. Kirby was found guilty of second-degree murder and ordered to serve seven years in prison for killing her husband. According to the Richmond Dispatch, she was a lucky woman. Ten of the twelve jurors had held out for a first-degree conviction, but agreed to the lesser charge to avoid prolonged deliberation. Annie began serving her sentence on November 11, 1867, however, her jailhouse days were numbered. On November 23, Governor Francis Harrison Pierpont (provisional governor, 1865—1868) pardoned Mrs. Kirby of any wrongdoing, apparently swayed by a petition begging for her release. She was granted her freedom and reportedly left Richmond for Petersburg shortly thereafter.

144 YEARS LATER…

What we do not know about this story truly outweighs what we do. Did this young woman fool the doctors, the jury, and the Governor with a well-planned and clever ruse? Did jealous love drive Annie Kirby insane or did she kill her husband in cold blood? Annie’s story, as found in the Western State Hospital case book, ends with her pardon—but what happened afterward? Perhaps Annie left Richmond, died, remarried, or changed her name. Searches of the census reveal little conclusive evidence of Annie’s whereabouts after the scandal. We may never know all of the answers, but Annie Kirby’s story transcends time as it reveals how little has truly changed when it comes to love, jealousy, and the complexity of the human mind.

UPDATE!

“Murder at the Second Market” was first published in the former Virginiana section of the Virginia Memory web site in early 2009. Shortly after the story was featured, I was thrilled to receive an email from the great-great granddaughter of Annie E. Kirby herself! For many years Annie’s descendents had come up empty-handed when tracing her early history. As a result, the story found in the Western State Hospital records and various newspaper articles filled in many blanks for them. Luckily for me, the great-great granddaughter was able to share information about Annie’s life after her pardon, the point where my research had previously hit a dead-end.

According to family history, in 1872 Annie married a man named Henry Clay Rhodes and had four children with him. I checked the 1880 census and found Henry (“H.C.”) and Annie (“Anna”) living in the Monroe Ward of the City of Richmond (possibly Henrico County). Annie’s three teenage sons from her marriage to Robert Kirby were living with them as were all four of Henry and Annie’s young children. (It is from one of the Rhodes children that the correspondent is descended). The great-great granddaughter believes that Henry and Annie later divorced, a claim which appears to be confirmed by the 1900 census in which Henry C. Rhodes is noted as living alone and “divorced” in the Monroe Ward. In that same census, Anna E. Rhodes is found to be living as a “widow” with her daughter Mary in the Jefferson Ward of the city. Why she is listed as a widow is unclear. Annie’s exact date of death is unknown, but the great-great granddaughter believes that Annie died sometime between 1900 and 1910, as a conclusive “sighting” of her in the census records after 1900 has not been located.

Many thanks to Annie’s relatives for solving this archival mystery!

The Western State Hospital collection is open to researchers. However, it contains privacy protected information. Researchers should review the access and use restrictions prior to using this collection.

-Jessie Graham, Senior State Records Archivist

UPDATE Part Two! [3 March 2011]

Inspired by Jessie’s update, I conducted some additional research on Annie Rhodes in an underused non-archival resource: the Virginia Digital Newspaper Project. The Virginia Digital Newspaper Project (VaDNP) is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) and is an ongoing initiative to provide free access to text searchable digital images of historical newspapers. The NDNP has partnered with the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and an ever growing number of awardee states to provide this content, which can be found on the Chronicling America site.

The goal of the VaDNP is to digitize 300,000 pages of Virginia newspapers published from 1860 to 1922 by the end of 2010. Please click here to see a list of newspaper titles along with available dates that are currently online for searching. The Chronicling America repository and database is text searchable and provides full page images with crop, zoom, and print features. A brief history and a complete bibliographic record are also available for each title at the Chronicling America site. The Chronicling America repository has more than one million pages of digitized U.S. imprint newspapers.

A key word search on Annie Rhodes revealed the date of her divorce from Henry C. Rhodes (4 November 4 1901) and an attempt on her life by Lyman and J.R. Stultz (7 June 1900). I also discovered that Annie’s son William J. Rhodes killed a man. On 29 January 1900, Rhodes learned from his wife that W. Frank Barnett had visited their home and taken advantage of her. Incensed, Rhodes shot Barnett in the head; he died three days later. Rhodes was tried for murder and acquitted on 12 May 1900. The jury deliberated for only six minutes.

If you wish to learn more about these stories, please consult the newspaper articles listed below.

Annie Rhodes

“Wanted to Take Her Life,” Richmond Times, June 8, 1900, page 8, column 2.

“Thrust Pistol in Her Face,” Richmond Dispatch, June 8, 1900, page 1, column 4.

“For Threatening Mrs. Rhodes,” Richmond Dispatch, June 9, 1900, page 1, column 2.

“Sticky Day in Police Court,” Richmond Times, June 13, 1900, page 6, column 1.

“Hustings Court to Meet,” Richmond Times, November 5, 1901, page 6, column 6.

William Rhodes

“Bullet in His Brain, Frank Barnett Shot Down by W.J. Rhodes,” Richmond Dispatch, January 30, 1900, page 1, column 5.

“Result of Inquest,” Richmond Times, February 3, 1900, page 7, column 3.

“Rhodes Goes to a Jury,” Richmond Dispatch, February 4, 1900, page 11, column 4.

“Rhodes Hopes for Acquittal,” Richmond Times, March 21, 1900, page 4, column 6.

“Rhodes on Trial To-day,” Richmond Times, May 10, 1900, page 7, column 2.

“Rhodes Case this Morning,” Richmond Times, May 11, 1900, page 1, column 2.

“Tells Why He Shot – Rhodes Says He Killed Barnett for Wrongs to His Wife,” Richmond Dispatch, May 12, 1900, page 1, column 1 and continues on page 3, column 6.

“The Richmond Murder Trial,” Alexandria Gazette, May 12, 1900, page 2, column 2.

“Wm. J. Rhodes was Acquitted in Six Minutes,” Richmond Times, May 13, 1900, page 1, column 6 and continues on page 6, column 3.

“Rhodes Not Guilty,” Richmond Dispatch, May 13, 1900, page 1, column 4 and continues on page 19, column 3.

-Roger Christman, Senior State Records Archivist

(Originally posted on VA-ROOTS listserv 3/2/2011)

[This is from FamilySearch.org’s web site]

record title: Virginia Deaths and Burials, 1853-1912

name: Annie Rhodes

gender: Female

death date: 24 Dec 1905

death place: Richmond, Virginia

age: 59

birth date: 1846

birthplace: Va

race: White

marital status: Widowed

indexing project (batch) number: B06977-0

system origin: Virginia-EASY

source film number: 2033601

record title: Virginia Deaths and Burials, 1853-1912

name: Annie Rhodes

gender: Female

death date: 24 Dec 1905

death place: Richmond, Virginia

age: 59

birth date: 1846

birthplace: Va

race: White

marital status: Widowed

indexing project (batch) number: B06977-0

system origin: Virginia-EASY

source film number: 2033601

Thanks for the information Ann!

Thanks Ann! The Richmond City Death Certificates at the Library of Virginia are the source of Family Search’s information. Rhodes died from chronic diarrhea.

The information on FamilySearch.org’s web site is incorrect: Annie was not born in Virginia. After much research on behalf of my mother: Annie’s Great GrandDaughter. We have family information of Annie’s birth and death. The dates are correct. Thanks Kimberly

Annie E Rhodes’ G-Great Grand Daughter

You are correct—Annie was born in Ireland. We all know how notoriously inaccurate recordkeeping could be back then. Who knows who supplied her information for the death certificate.

I did a little nosing around and found some census records for who I think were her sons from her first marriage and they list their mother as being born in Ireland, which matches what I found in my research. Obviously, this isn’t totally reliable, either. Thanks for you comment. -Jessie

Those Kirby boys are my ancestors, including John, my ggrandfather.

I have information on Annie’s Kirby sons. The youngest, John, was my great grandfather.

I am the great granddaughter of Annie and Robert Kirby’s youngest son, John, born in 1865. The Kirby boys (also Robert and Thomas) apparently were disinherited by their mother and did not share in Robert’s estate. They moved to New York City and remained estranged from their mother. John came to Philadelphia where he married my ggrandmother, Jennie Ruby, and the family has been in this area ever since. We knew Annie killed Robert but could not find court records. This is good information.

Do you mind me asking how you got access to the records at Western State Hospital in Staunton, Virginia. My 3rd Great Grandfather and one of his sons were at this hospital and I would like to access the information for my family tree.

Ms. Howard,

The historical records of the Western State Hospital are housed here at the Library of Virginia. You can find information on the collection by viewing the finding aid at search.vaheritage.org/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi00937.xml

Keep in mind that some records have restrictions due to privacy laws. If you have questions about using the materials after reviewing the finding aid, please contact Archives Research Services at 804-692-3888 or archdesk@lva.virginia.gov.