The Prince George County chancery causes are filled with numerous divorce cases involving cheating spouses and adulterous affairs, but in the case of Thomas P. Kelly vs. Josephine Kelly, 1893-001, there is also a bit of baby daddy drama. The divorce suit involves Norfolk native Thomas Kelly, who had been for many years enlisted as a machinist in the United States Navy. During the year 1888, Thomas Kelly was stationed on board the monitor fleet lying at anchor at City Point in Prince George County. There he met Josephine Hodges, who was sixteen years of age. As Kelly would later testify in the chancery cause, their relationship began as a friendship and culminated in intimacy. Kelly confessed that he had sexual intercourse with her on or about the 17th day of June 1888 and also with more or less frequency from that date until he was transferred with the fleet to Richmond in October of the same year.

About the first of January 1889, Thomas was informed that Josephine was pregnant and that her condition was attributed to him. Her friends and her mother’s friends, including the pastor of her church, made repeated and urgent endeavors to have Thomas agree to marry her, but as there had been no promise of marriage and no undue advantage taken by him, he refused to comply with their wishes. Finally it was urged that the suggested marriage would not only save the girl from ruin but would relieve his child from the stain of illegitimacy. Thomas finally gave in and they were married on the night of 5 January 1889. A few hours after the marriage, Josephine was in labor, and about 9 or 10 o’clock the next night she delivered a son, who was named after his father, Thomas P. Kelly. Thomas was at first greatly surprised the child would be born so soon, but supposing that its birth was prematurely brought on by the excitement of the marriage, he dismissed from his mind all thoughts suggesting improper conduct on the part of his wife and cared for her and his child “with all the tenderness of which he was capable, giving freely of his time, attention, and money to provide for their welfare and comfort.”

Although its mother and father were both fair, the baby’s coloring was dark, but Thomas Kelly did not have his attention drawn specially to the baby’s appearance until sometime after its birth because his duties with the navy kept him away from home most of the time. Thomas visited his wife and son on 5 November 1889 and was struck with the fact that the child had grown very dark in color, which caused him great uneasiness and aroused his suspicion. In discussing the matter with his wife, “she bullied him into quietude by her positive assurance that the child’s peculiar complexion was due to the fact she had taken large quantities of medicine before its birth.” Thomas, not doubting her statement, went back to his port of duty and did not return again to City Point, where his wife and his child had always resided, until 18 January 1890.

Upon his return, Thomas found the “child was blacker than ever, its lips were grown thick, its nose flat, and its hair having the unmistakable wooly kink – altogether showing plainly that Negro blood flowed in its veins.” Thomas, though shocked at the evidence which was presented to his own eyes, hesitated at first to communicate to his wife the connections he was making. But the more he tried to down the thought, the firmer hold it had upon him, and in his desperation, he stated to his wife that he was satisfied the child was not his. “A scream followed and amid tears of anguish” his wife confessed to him that he was not the father and that the real father was an African American named James Laundy. (However, a deposed witness identified the father as “General Sherman,” whose real name was thought to be William.) Josephine admitted she had sexual intercourse with another man on 11 April 1888 – the same confession being afterwards made to her mother and to other members of her family. In an instance the “whole scheme of deception” became apparent to Thomas Kelly and “in righteous indignation” he immediately left his wife and refused to recognize the marital relation existing between them. After separating from his wife, Thomas was informed by many people living at and near City Point that they had for some time believed that the “child was begotten by a Negro, but in consequence of the delicate nature of the case did not feel justified in expressing their opinions to him.”

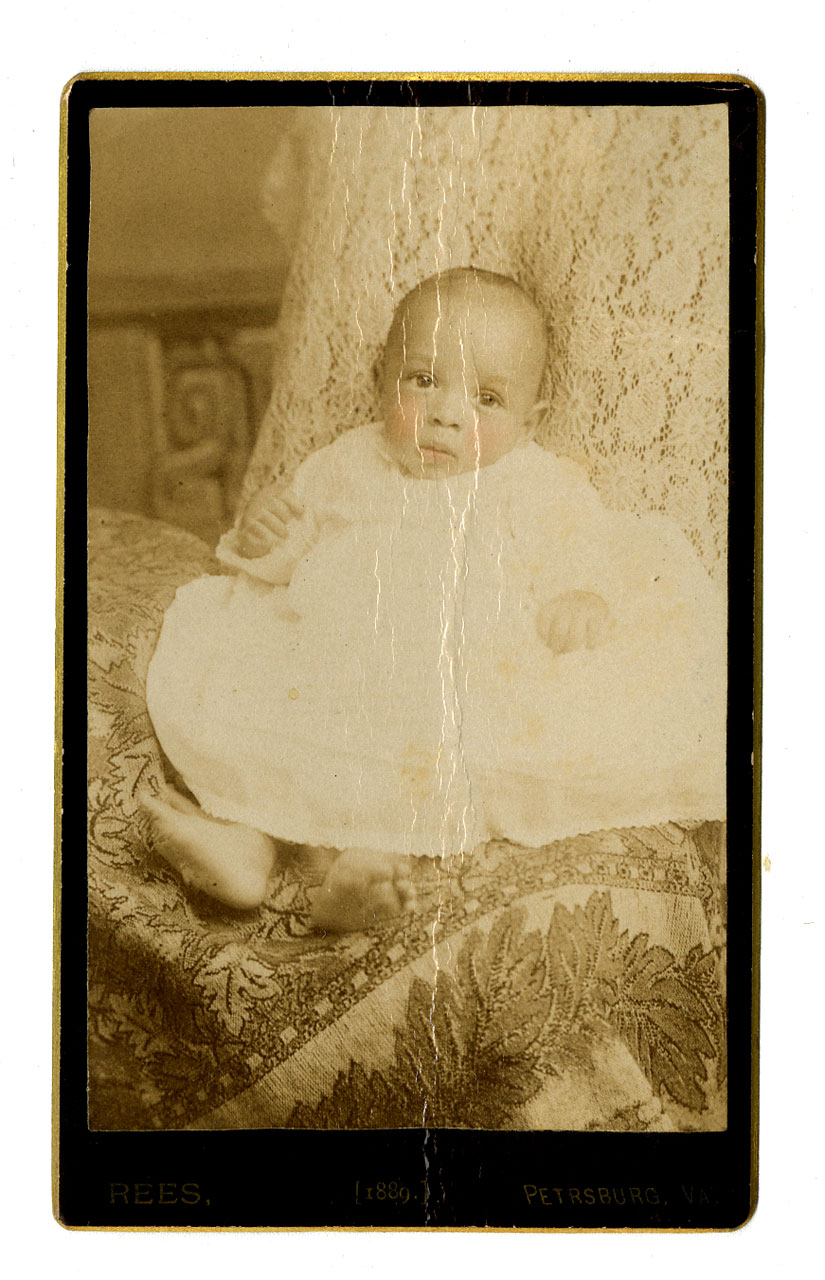

In his bill for divorce filed in 1890, Thomas Kelly charged that at the time of his marriage on 5 January 1889 his wife was with child by some person other than him and that he believed that such other person was a Negro. As evidence to support his claims, Thomas submitted a photograph of his wife’s son. Thomas also claimed that after he left his wife, she had disposed of her child to certain African Americans in the city of Petersburg with the understanding that they would rear him as their own “thus emphasizing the grievous wrong which she perpetrated on her unsuspecting husband” in an attempt to hide her own disgrace. Thomas turned to the courts seeking the relief afforded by divorce stating that “the road of affliction had been laid heavily upon him and that his cup was full of bitterness,” but in 1893, for reasons not stated in the case, he requested that the divorce suit be dismissed.

The Prince George County chancery causes are currently closed for processing. Because of reductions to the Library of Virginia’s budget in recent years, the pace of the agency’s digital chancery projects will necessarily proceed more slowly. Please know these projects remain a very high priority for the agency and it is hoped that the initiative can be resumed in full when the economy and the agency’s budget situation improve. Please see the Chancery Records Index for a listing of the available locality chancery collections.

-Sherri Bagley, Local Records Archivist

What a great post Sherri! Maury Povich would be proud.

Thanks for posting.