Another presidential election year is upon us, and we are already bombarded with television ads touting the two candidates and proclaiming their positions on every issue from A to Z. Will 2012 be an election for the history books or will it be relegated along with other campaigns to the dustbin of history? You may remember the elections of 1800 (Jefferson’s “Revolution of 1800”), 1860 (the election that sparked the Civil War), 1932 (FDR, Hoover, and the Great Depression), and 1984 (Reagan’s “Morning in America”). But what about others? Quick, without Googling it—who ran against Teddy Roosevelt in 1904?

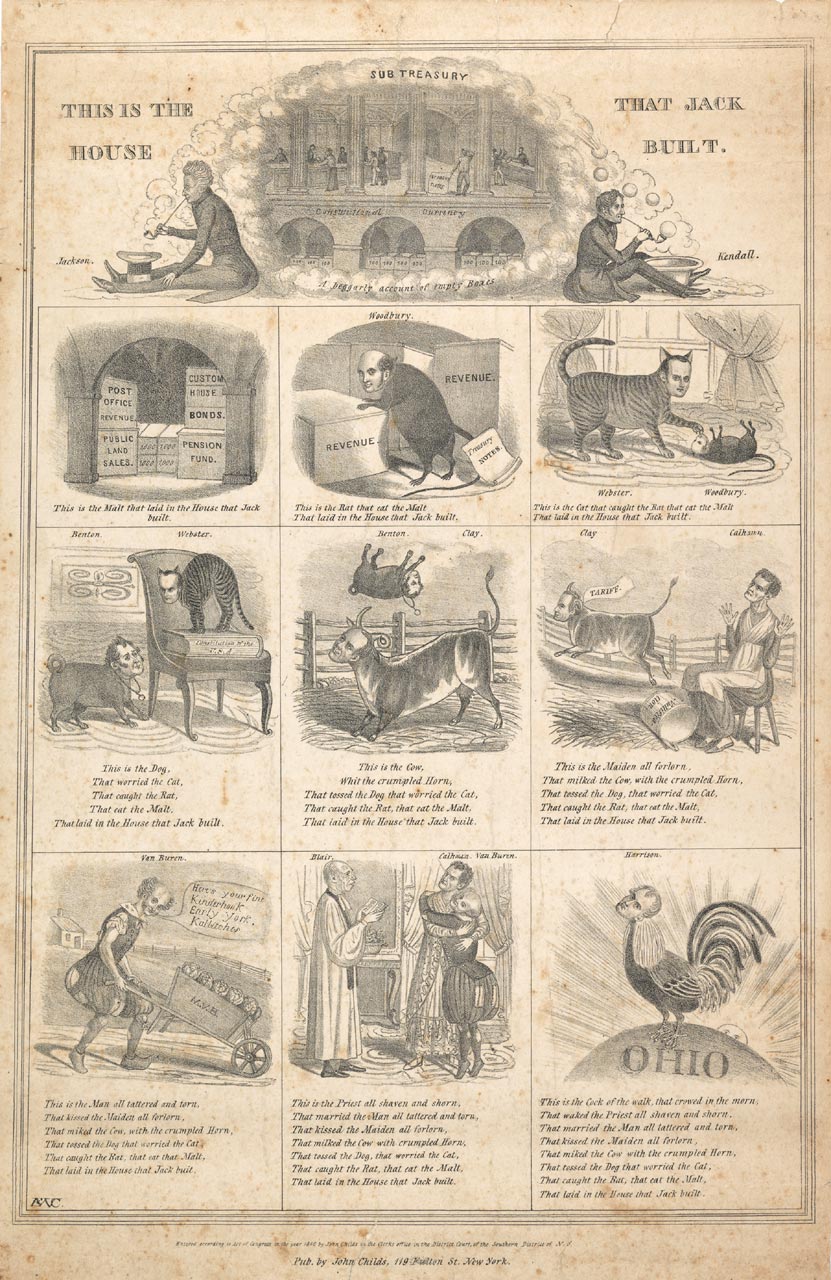

The election of 1840 mostly falls into the dustbin file. It is usually remembered only because of a catchy campaign slogan (“Tippecanoe and Tyler too!”) and the fact that the winner, second-rate military hero William Henry Harrison, served only one month before becoming the first president to die in office. Yet 1840 was a key election year, and a broadside found in the Library of Virginia’s collection reveals some of the issues at play. Entitled “This Is The House that Jack Built” (LVA accession 28192), this 1840 political cartoon by John Childs utilizes the nursery rhyme of the same name to illustrate the views of Harrison’s Whig Party.

Four years earlier, the Whig Party had formed in opposition to President Andrew Jackson, coalescing around Henry Clay’s “American System”—a tariff to encourage domestic manufacturing, federally funded internal improvements, and a national bank to regulate the national economy and finances. In 1840, the Whigs ridiculed the incumbent Martin Van Buren and the economic policies he inherited from Jackson. Their “commercials” were often broadsides like this one, which satirized the Jackson and Van Buren administrations’ financial and economic policies that the Whigs believed were responsible for the Depression of 1837 and the sluggish growth of the economy. While the references found in this cartoon are obscure to most modern readers, they were quite controversial at the time.

This sort of propaganda struck a chord, and the Whigs succeeded in 1840. With 80% of eligible voters casting ballots, Harrison was elected president and the party gained majorities in both houses of Congress. The American System seemed poised for passage. But on 4 March, the 68-year-old Harrison, hatless and with no overcoat, delivered a 105-minute-long inaugural address in the cold rain. He caught a cold which became pneumonia and died one month later, on 4 April. Vice President John Tyler, an anti-Jackson states righter, succeeded to the presidency. More loyal to states rights than to Whig philosophy, Tyler vetoed the Whig-passed national bank bill. The new president (“His Accidency”) defeated his own party’s goals.

The Whigs elected another military hero president (Zachary Taylor, “Old Rough and Ready”) in 1848 and remained competitive in elections until collapsing under the weighty issue of slavery in the 1850s. But the party never had another chance like 1840 – a chance, had Harrison lived, to alter the course of American history. Only after the Civil War did a party with a similar agenda to the American System implement it. Maybe all those uninteresting elections, which only come alive for us now in rare relics like “This Is The House that Jack Built,” had profound consequences after all.

“This Is The House that Jack Built” (LVA Accession 28192) is available for research at the Library of Virginia.

-Trenton Hizer, Senior Finding Aids Archivist