Television and copy advertisements for prescription drugs are a common sight these days. But the obsession with finding the latest and greatest cure-all is nothing new. At the turn of the twentieth century, before the discovery of antibiotics and other wonder drugs, consumers were desperate to find palliatives for problems ranging from the common cold to cancer. The search for the perfect panacea combined with the huge number of newspaper readers made newspapers the primary medium for shrewd concoction makers to hock their potions. The medicinal advertisements below are from the Alexandria Gazette, the Daily Times (Richmond, Va.) and the Free Lance (Fredericksburg, Va.) of 1899-1911 and represent companies which were successful thanks, in part, to convincing and pervasive newspaper advertising campaigns. All images are from Chronicling America, a digital repository of historic newspapers. Original and microfilm copies of these papers can also be found in the collections of the Library of Virginia.

Ely’s Cream Balm, manufactured by the Ely brothers of Owego, NY, was a popular remedy for catarrh, “an Inflammation of the mucus membranes in one of the airways or cavities in the body.” The Ely Brothers started producing Ely’s Cream Balm, a compound similar to today’s Vicks VapoRub, in Owego in the early 1860′s. They moved the company to New York City in the early 1890′s and it was later sold to Wyeth in the mid 1930′s. In this ad from January 1, 1910 in the Alexandria Gazette, an illustrated head appears with congestion-causing ailments written all over it.

In bold, capital letters, the ominous words CATARRH and HEY FEVER appear at the top and bottom of the afflicted head. It calls itself a “reliable remedy” that “cleanses, soothes, heals and protects the diseased membrane resulting from Catarrh.” In the days when quackery medicine was the norm, Ely’s Cream Balm probably did seem a reliable remedy for stuffy noses. The cost for a bottle of Ely’s: 75 cents.

In 1883, Meyer purchased all interests of the partners and the company became A.C. Meyer & Co. While newspaper ads claimed that Dr. Bull’s was gentle and affective for children, The Great American Fraud: Articles on the nostrum evil and Quackery reprinted from Collier’s (October 1905) asserted that Dr. Bull’s original formula contained morphine (later replaced by codeine) resulting in several deaths.

In these ads from the Alexandria Gazette of 1900, the safety of Dr. Bull’s is continually emphasized. A picture of a young mother giving her little girl Dr. Bull’s reads “A child’s stomach and brain are not to be trifled with. Some medicines cure coughs but injure otherwise—perhaps permanently. Dr. Bull’s is harmless, sure and quick.” Another ad shows a proud grandfather with his brood of vigorous grandchildren, “It may save your life some day-it has saved lots of others. . .it can’t hurt even the smallest or sickest child—and it cures.” Well, maybe not.

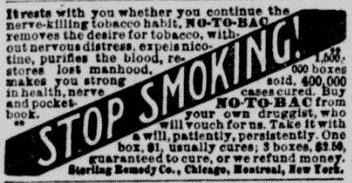

Sterling Remedy Company was founded by H. L. Kramer to market No-To-Bac, a remedy to help quit smoking. “No-To-Bac removes the desire for tobacco,” said its newspaper ads, “without nervous distress.” Apparently No-To-Bac also expelled nicotine, purified the blood, and even restored lost manhood. In 1905, three boxes of No-To-Bac sold for $2.50. An unfortunate side effect of No-To-Bac, however, was that it caused severe constipation, so Kramer’s company developed the product “Cascarets” to counteract the problem. Cascarets Candy Cathartic went on to become much more successful than the No-To-Bac product. In 1906 William E. Weiss and Albert H. Diebold, makers of the pain reliever Neuralgine, purchased the Sterling Remedy Company and changed the company’s name to Sterling Drug, which operated until 1994.

In 1879 businessman Zeboim Cartter Patten and a group of friends established the Chattanooga Medicine Company in Chattanooga, Tennessee. The company’s first two products, Black-Draught, a senna-based laxative, and Wine of Cardui, a uterine sedative, were wildly successful and continued to sell well into the twentieth century. According to legend, Wine of Cardui originated among the Cherokee Indians. Advertised as a “Woman’s Tonic,” it supposedly helped backache, headaches, dizziness, difficult menstruation, leucorrhea, and any general female disorder.

Cardui ads commonly used testimonials to show the product’s effectiveness. “In a Bad Fix” reads one ad from a 1910 issue of the Alexandria Gazette, “I suffered greatly with ailments due to the change of life and had three doctors, but they did no good, so I concluded to try Cardui. Since taking Cardui, I am so much better and can do all my house work.” Cardui was a 38-proof patent medicine, so its medicinal powers might have been due to its high alcohol content.

In 1868, the US Patent Office granted a patent to Dr. Samuel Pitcher of Barnstable, Massachusetts, for Pitcher’s Castoria, a laxative compound of senna, sodium bicarbonate, essence of wintergreen, taraxacum, sugar and water. In 1871, the Centaur Company, formed by Charles Henry Fletcher, purchased the rights to Pitcher’s Castoria and renamed it Fletcher’s Castoria. The product was heavily advertised on billboards in cities during the late nineteenth century. Fletcher’s Castoria ads were also a mainstay in newspapers at this time and remained so well into the twentieth century.

This ad, from the Free Lance July 8, 1911, assured the user that it was “The Kind You Have Always Bought.” “What is Fletcher’s Castoria?” the ad asks, “Castoria is a harmless substitute for castor oil…the children’s panacea-the mother’s friend. Genuine Castoria always bears the signature of Char. H. Fletcher.” The Centaur Company was acquired by Sterling Drug during the 1920s.

As a young physician, James C. Ayer created a Cherry Pectoral for pulmonary complaints which became a popular remedy in the 1850s. In 1855, James and his brother, Frederick, joined forces to become J.C. Ayer & Co. and amassed a fortune producing medicinal products out of Lowell, Massachusetts. Key to the company’s success was its affective and ubiquitous newspaper advertising. Ayer’s Sarsaparilla, one of the company’s signature remedies, claimed to have all sorts of curative powers but was actually just herb flavored water similar to root beer.

In this ad, a robust older gentleman holds a bottle of Ayer’s Sarsaparilla in his hands. The ad reads: “Either as a Tonic or Blood-purifier, Ayer’s Sarsaparilla has no equal!” The price for one bottle was a dollar, but the ad claimed it was “worth five dollars of any man’s money.”

In 1882 Milton K. Paine, a pharmacist from Windsor, Vermont, began bottling his Celery Compound, an all-purpose panacea containing celery seed, red cinchona, orange peel, coriander seed lemon peel, hydrochloric acid, glycerine, simple syrup, water and alcohol. Paine’s Celery Compound was a big hit with consumers and was later marketed by the Wells Richardson Company located on College Street in Burlington, Vermont. Paine’s Celery Compound advertisements were printed regularly in newspapers at the turn of the century. The product’s ad campaign employed elaborate illustrations and convincing testimonials of its healing powers. In this ad from May 5, 1899 of the Free Lance, Miss M. A. Armstrong, a government “microscopist” who has painstakingly studied the compound, “heartily recommend[s] it” and gives it her “highest endorsement.”

It promises it can restore vigor and health explaining that, “The use of Paine’s compound makes all the difference between impure, sluggish blood and tired nerves and healthy, energetic bodily condition—between sickness and health.” With claims like that, how could anybody resist trying it?

For centuries mineral water has been touted for its medicinal benefits. “The principles of hydrotherapy have occupied a time honored position in man’s arsenal against disease and infirmity,” writes Arthur Wrobel, author of Pseudo-Science in 19th Century America, “Hydropathic remedies have enjoyed a continuum in the annals of medical practice from antiquity to the present.(p. 74)”

Otterburn Lithia and Magnesia Springs Water, manufactured in Amelia, Virginia, claimed to be the “Greatest known water for Dyspepsia, Indigestion, Kidney and Liver troubles.” In a study done by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1905, the composition of Otterburn water had been determined not to differ “materially from the advertised analysis. However, it is a misnomer to call it a lithia water, as it would take approximately 1,000 liters to give a full medicinal dose of lithium.”

And then there’s exercise! Fresh air and vigorous exercise were promoted for good health in 1905 just like they are today. This ad for Adam’s Book Store from the May 4, 1899 edition of the Free Lance shows a young man riding a bike “prolonging his life” through “healthy sports and exercise in the open air.” Apparently Adam’s Book Store not only sold bike wheels, but baseball and tennis goods as well. What books were for sale, however, were not mentioned in the ad.

For a history of Cascarets Candy Cathartic, visit the Candy Professor Blog