In 1902 Louisiana became the first to pass a statewide statute requiring mandatory segregation of streetcars, followed by Mississippi in 1904. That same year, Virginia authorized, but did not require, segregated streetcars in all of its cities, leaving it up to companies to decide whether or not they would segregate their services. On April 17, 1904, the Times Dispatch printed the article “Separate the Races” on page seventeen of its Sunday edition, in which the Virginia Passenger and Power Company outlined a new set of rules. The Company surely hoped its new policy to enforce racial segregation on its cars would go unnoticed by Richmond’s populace. Instead, the company’s new regulations led to a citywide boycott of its services and most likely hastened its financial demise.

“This company has determined to avail itself of the authority given by a recent state law to separate white and colored passengers,” read its statement in the Times Dispatch, “and to set apart and designate in each car certain portions of the car or certain seats for white passengers and certain other portions or certain seats for colored passengers. . .The conductors have the right to require passengers to change their seats as often as may be necessary for the comfort and convenience of the passengers and satisfactory separation of the races.” White riders were to sit in the front of cars, while black riders were to sit in the back, but because there were no permanent partitions on the cars, conductors had the authority to assign seats as the ebb and flow of black and white riders shifted.

This gave conductors the power to play a “bizarre game of musical chairs with passengers.”[1] The company’s new regulations also gave conductors the authority to arrest or forcibly remove anyone who did not comply with its policies. “If passengers refuse to move their seats or their positions in the car in accordance with the reasonable, proper and courteous demand of the conductor” the article explained, “they should be arrested by the conductor or removed from the car.”

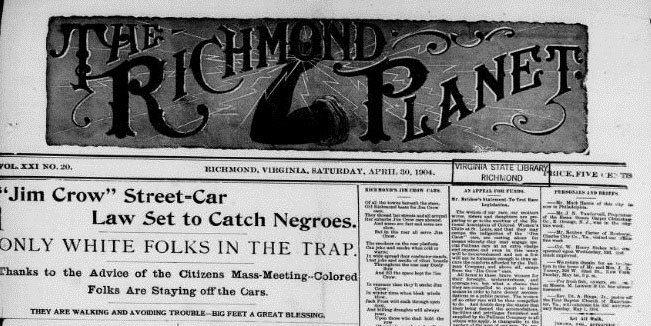

As more and more states in the South passed laws mandating segregated streetcars, most major southern cities experienced some form of protest from the African American community. On April 19, 1904, two days after the company’s announcement, a mass meeting was held in Richmond to protest the new streetcar rules. Taking the lead at the meeting was John Mitchell, Jr., the “fighting editor” of the weekly Richmond Planet. The front page of the April 23 issue of the Richmond Planet reported on the meeting and pointed out that “the law passed by the recent legislature with reference to the street-cars did not require that the separation be made.

It was left to the street-car companies entirely. They could put it into effect or they could decline to do so. . .There was no general demand on the part of the white people for this law. . .it was the arbitrary act of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company.” Not only was segregation demoralizing and unfair, but people feared a potential abuse of power by white conductors. While the Virginia Passenger and Power Company’s statement asserted that the “successful carrying out of this law depends largely upon the judgment and goodness of the conductors, whose duty it is to enforce it,” the St. Luke Herald explained, “the very dangerous power placed in the hands of hot headed and domineering young white men. . .would certainly provoke trouble.”[2]

At the meeting, attended by several distinguished men and women in Richmond’s African American community, Mitchell advocated peace between the races. He also expressed concern that the company’s new policies were being enacted not to quiet racial strife, but to incite it. “He [Mitchell] showed that under the provisions of the law that the white boys and ill-mannered men. . .were empowered to carry revolvers and if they shot down colored men, they could not be punished for so doing.” Mitchell felt the only way to avoid such abuse of power and potential conflict was for Richmond’s African American community to “to stay off the cars” and boycott the streetcar system. The meeting ended with a resolution that the citizens of Richmond “enter our solemn protest against the enforcement of this law by any and all public service corporations, recognizing as we do that the enforcement of the law in question is left to the option of such companies.”[3] And so, on April 19, 1904, a boycott of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company began.

The racial divide on the streetcar issue is clearly discernible in the local newspaper coverage of the time. White run newspapers throughout the South tended to ignore protests against segregation, while African American newspapers continually re-enforced the need to protest. “Local white papers had every reason to de-emphasize—even ignore the boycotts,” explained Meier and Rudwick, ”Neither in Memphis nor in Atlanta did the daily press even mention the ones in their own cities. And where the local dailies reported the beginnings of a boycott, almost invariably the editors seem to have decided, after a certain point, that continuing discussion was no longer in the public interest.”[4]

This was certainly the case with the Times Dispatch (T-D). After the initial changes in policy were made by the streetcar company, the T-D ran a surprisingly even-handed article “The Negroes Will Walk” on April 20, 1904. “For nearly three hours last night,” the T-D reported, “six hundred or more negroes of all trades and many factions, in mass meeting assembled, discussed, deliberated and counseled over the new laws that go into effect today, and with wild enthusiasm declared . . .that the black man shall desert the streetcars of Richmond. . .and plod his daily way along as best he can.”

The T-D also reported that the protest was not an “ominous disturbance” but a “calm, but positive, assertion by these negroes to refuse to accept the terms offered them by the company in return for their fares.” The Richmond News Leader‘s report of April 20 claimed that the result of the meeting was that “only a small percentage of negro patrons of the Passenger and Power Company walk today.” It went on to say that the protest had only succeeded in creating factional lines within Richmond’s African American community, with men like Mitchell on one side and those ready to acquiesce on the other.

After these articles, however, very little was reported on the front pages of the Times Dispatch or the News Leader on the boycott. “From the beginning,” writes Ann Field Alexander, author of Race Man, “the transit company took no official notice of the boycott, and the white press downplayed its significance. . .the testimony of the white press was unreliable, however, and back-page articles occasionally belied front page news.”[5] The occasional editorial appeared on the subject as well. On April 20, 1904 the editor of the Richmond News Leader wrote on the subject, saying segregation was “as necessary as it is natural. It is one of the safeguards against the breaking down of the barrier between the races. . .which is the worst horror Southern white people can imagine.”

Mitchell’s Planet, on the other hand, ran a front page story on the streetcar boycott in nearly every issue until the Virginia Passenger and Power Company finally went out of business late in 1904. Week after week, articles in the Planet encouraged the African American community to continue the boycott and strongly urged people to keep walking. Using his newspaper as a mouthpiece, Mitchell worked tirelessly to maintain momentum against the growing menace of complete segregation. The Planet’s May 7, 1904 issue reported, “The street-car situation remains unchanged. Few colored people are riding in the ‘Jim Crow’ department.” The front page of May 14, 1904 stated that the “street-car situation here remains the same. Eighty or ninety percent of the colored people are walking.” The June 11, 1904 issue published words to the “Jim Crow Street-Car Song” and on August 20 an article titled “Equal Rights Before the Law” showed just how unequal Jim Crow was. The article explained that a white man who didn’t know the streetcar rules had been forgiven of his Jim Crow offense, while Addie Ayres, the maid of local actress Mary Marble, was arrested and fined ten dollars when she declined to move after a conductor ordered her to do so.

Although momentum for the boycott slowed during the stifling summer months, the Planet’s continued efforts to sustain it may have helped hasten the bankruptcy of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company. On July 23, 1904, the Planet ran the story “The Street Car Co. Here Busted.” By December 3 of that year, the Planet reported that the “Virginia Passenger and Power Co., better known as the ‘Jim Crow’ Street Car Company continues to have no end of trouble and it now seems that the entire system will be sold at auction.” While the boycott probably did contribute to the company’s collapse, it blamed its failure on the 1903 conductor’s strike, not acknowledging the effects of the boycott. After the local streetcar system was taken over by new management, the policy to segregate continued. In 1906 the Virginia legislature passed a mandatory law “to provide separate but equal compartments to white and colored passengers.” Passengers and companies who failed to comply would be guilty of a misdemeanor and fined. Sadly, Mitchell’s courageous and persistent fight to end segregation ended with Jim Crow even more firmly entrenched in Virginia.

Footnotes

[2] August Meier, Elliot Rudwick, “The Boycott Movement Against Jim Crow Streetcars in the South, 1900-1906,” The Journal of American History, Volume 55, Issue 4 (Mar. 1969): 761.

One Comment