You have no idea how awfully much I hated to leave you…Even if I can’t hear from you just now I feel sure you are thinking of me a little, aren’t you darling? Because you must know that you are dearer, and sweeter to me than life itself and I do love you.

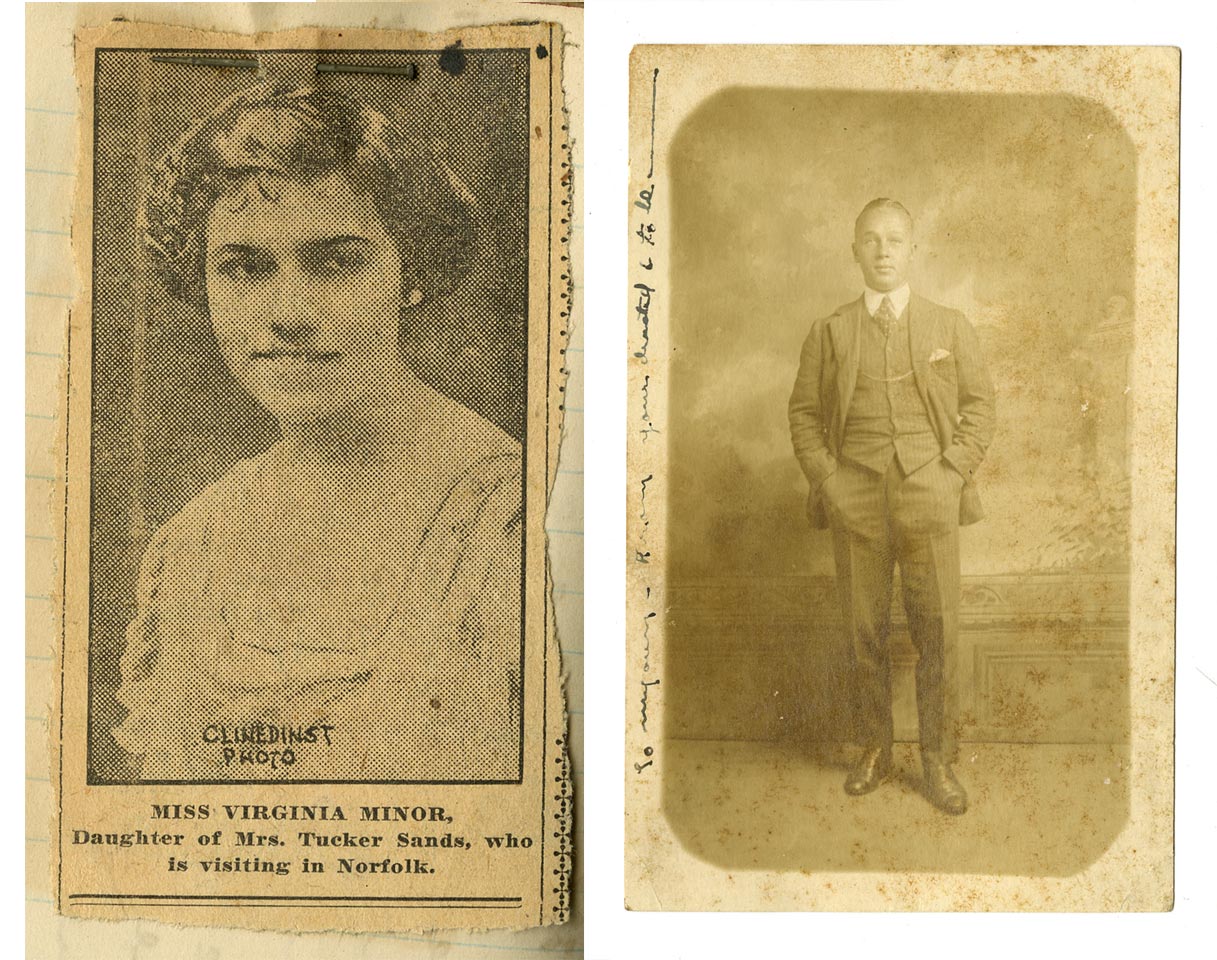

So wrote Robert B. Roosevelt, Jr., to his sweetheart, Virginia Lee Minor, on 18 March 1919. The letter is the first in a collection of correspondence kept by Virginia that now forms the better part of the Virginia Minor Roosevelt Jones Papers (Acc. 45319) at the Library of Virginia. Almost all of the letters were written by “Bob” to his “Miney,” and reveal a man consumed with love for his eventual wife. Sadly, they also show him struggling against an addiction that threatened his marriage before it even began, and ultimately contributed to his death.

So wrote Robert B. Roosevelt, Jr., to his sweetheart, Virginia Lee Minor, on 18 March 1919. The letter is the first in a collection of correspondence kept by Virginia that now forms the better part of the Virginia Minor Roosevelt Jones Papers (Acc. 45319) at the Library of Virginia. Almost all of the letters were written by “Bob” to his “Miney,” and reveal a man consumed with love for his eventual wife. Sadly, they also show him struggling against an addiction that threatened his marriage before it even began, and ultimately contributed to his death.

Roosevelt was the first cousin once removed of President Theodore Roosevelt, the son of Robert B. Roosevelt (1866-1929) and Lilie Hamersley Roosevelt (b. 1882). It is unclear how he met Virginia, but by the time this correspondence commenced, the two had entered into a seemingly new but already intense long-distance romance (he was living in New York City, she in Washington, D.C.).

The above quote is typical of the frequent declarations of devotion found throughout Bob’s letters. But another recurring theme first reveals itself in a relatively innocent-sounding statement in his 19 March 1919 letter. “Virginia the worst thing I have done since I left you was to take a glass of beer, and please forgive me,” he wrote. “I can just hear you saying that now.” What initially seems like a pre-emptive defense against a girlfriend’s lighthearted correction slowly reveals itself to be more serious, as similar statements begin to pile up in successive letters.

“I am tired, so tired of that life, but we all have to go through that stage,” he writes on 22 March. On 17 April, he begs–“Miney excuse me for acting like such a perfect child. I know you tried to make me do what is right, and you always have…I feel so badly about making certain things hard for you and I do hope you will forgive me.” A few days later (22 April) he professes himself to be “so awfully blue, and so sad, lonely, and depressed and God you don’t know how it hurts me, when I think of my sweet little Miney, saying she wished she were dead, and I thought you felt we both had such a wonderful future to live, just you and I.”

He constantly reassures her that she is the only woman he wants, and worriedly asks about her interactions with other men. At times when he does not receive a letter from her, he becomes almost despondent: “I hoped you were really sincere in every thing you said dear, but its [sic] awfully hard to believe it now…Its [sic] an awful life dear for me here, and you are the only ray of sun light in my whole life. Your love means all to me Virginia and I crave for it” (22 March 1919). In another letter, he notes that she had been engaged in the past, and fears that her love for him would die as it had for the other man.

Roosevelt speaks often of working to make himself worthy of her, and to enable their eventual marriage, as he did on 18 June 1919:

Really dear if I didn’t love you so awfully much, and didn’t think you really cared a lot for me, I would feel life wasn’t worth living. For I feel I’ve seen and been through too much of it, and I am damn tired of it to be truthful, I mean the so-called social life…I realize dear it is a damn shame that we are so happy together and that we have to be separated, but on the other hand try and look a little into the future, you realized when I was with you that we couldn’t get married under the existing conditions, and I am doing the only right thing by you…I often wondered where I would be now if I gave way to all my feelings as you put it. I guess more than probably in jail…

He mentions being followed by a doctor, and continually asserts that he will avoid alcohol, even while admitting to a few slips here and there: “I did go on a little party dear, but at no time did I not know everything I was doing…I only wish you could be around me when I didn’t know it and see me and my actions when your [sic] away” (9 July 1919).

Allusions to his drinking problem are paired with references to money troubles. He tries his hand at a couple of different jobs and plays the stock market in hopes of making enough money to be able to marry—“It certainly is a wonderful incentive to work like hell” (16 July 1919). He indicates in his 29 July letter that they will marry in December. But by early October he is headed down to Eastland, Texas, to try and make his fortune in the oil business.

A 3 October 1919 letter from Roosevelt’s mother encourages him on his way: “Now Bob you have your chance to prove all the good that’s in you, and there is plenty. My faith in you has never waivered. I know that you will succeed. Drink is the big temptation for you to fight, and you have to beat it, so start in and refuse to touch a drop. It has done you so much harm…I am very proud of you having the courage to go off as you have done and my daily prayer is for you and your success.”

At this point, there is a gap in the letters from Bob to Virginia, although some postcards sent by him to her from Texas are pasted into a small scrapbook she kept. The next letter is from a friend, congratulating the couple on their October 1920 marriage, which took place in New York City. Here again the record goes silent until mid-March 1922, when the letters from Bob to his wife (and new mother of son Robert Jr.), pick up again.

Writing from an address listed in the 1914 Medical Directory of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut as the Charles B. Towns Hospital for the Treatment of Drug Addiction, Alcoholism and Nervous Diseases, Roosevelt is making overtures to his now estranged wife: “Now dear be sensible and have a long talk with me when my head is absolutely clear and let us try to come to an agreement of some sort” (17 March 1922).

The next letter, postmarked 20 March 1922, shows Roosevelt angry and hurt, believing that his wife is lying to him about why she has not come to spend more time with him. “If you would lie to me about little things I have no reason to believe you wouldn’t lie to me about seeing other men or taking lunch and going out with them,” he writes. “If your thru [sic] with me for God sakes be woman enough to admit it, but we can’t go on this way and you must realize it.” Another letter, written later that night after again trying to call her and being told she was not in, is similarly reproachful and requests that she show his letter to his mother: “Maybe you can fool her better than your husband with an explanation.”

Things seem to have been smoothed over by the time he composes his 24 March letter. There is no mention of the recent unpleasantness, only renewed hope for the future: “Honey dear I too want a home somewhere for a wonderful loyal little wife whom I still adore and I want our child to be proud of his Father and I know you do too. We will both work together Miney and we will gain it back every little bit.” The next day’s letter assures her that “I really love you in my funny selfish way, but I will try not to be so selfish any more dear.”

The last letter from Bob to Virginia, postmarked 30 March 1922, describes a trip with his mother to Bayshore, New York, to begin cleaning out the home he and Virginia shared before she moved out. Two days later, he would be dead. A partial newspaper clipping in the collection notes that Roosevelt had been found on a New York City street late on the rainy evening of 31 March 1922, semiconscious and bleeding from the eyes, ears, and nose. A Dr. Gould (Roosevelt’s personal doctor) is quoted by the newspaper as saying that “he could not add to the police report that Roosevelt received his injuries in an ‘unknown manner while in a partly intoxicated condition.’ He said the injuries were so severe they could not have been inflicted by bandits or in a brawl. He said he believed Roosevelt had been run over by an automobile which sped away without halting to investigate the extent of his injuries.”

Virginia’s last letter to Bob, the only one found in this collection, is postmarked 31 March 1922. It is not known whether it reached Bob before he went out that fateful night, but likely echoes other letters he had received from his wife in the days leading up to his death:

Its [sic] too bad we couldn’t have been happy in the little home it was very sweet and cozy, but now the only thing to do is to try and start all over again and see if you cant [sic] make something of your life and make others happy who love you, that is if you really and truly want to do so.

Write me just what you are doing don’t deceive me any more please dear I would always rather know the truth no matter how hard it is.

Good bye dear. With lots of love, Miney.

The Virginia Minor Roosevelt Jones Papers (Acc. 45319) are open to researchers at the Library of Virginia.

-Jessica Tyree Burgess, Senior Accessioning Archivist

I would like to come and read these letters and try to find helen jones if she is still aliive I am a first cousin of robert roosevelt .am interested in the family history.

How interesting! Thanks for getting in touch. You are certainly welcome to come and take a look at the letters any time during our regular business hours (Mon-Sat, 9-5). Just go to the archives reading room at the Library of Virginia and request Accession 45319. I’m sorry I don’t have any information on Helen Jones, but I wish you luck in your family history research!