In some cases, failing extravagantly can work in favor of your cause. Go big or go home, as it were. John Brown was an American abolitionist who supported the use of violence to end slavery. A descendant of 17th century Puritans, Brown’s strong Calvinist beliefs would provide the moral inspiration for his battle against slavery. As we saw on The Abolitionists on PBS last Tuesday, Brown made a pledge in 1837 that would steer his actions in the coming decades: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!”

Unlike most white, well-educated, religiously-motivated abolitionists, Brown did not believe in solely non-violent means to end slavery. After the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850, Brown founded a militant anti-slavery brigade with the Biblically-inspired name “League of Gileadites.” Their mission was to prevent the recapture of escaped slaves by any means necessary. Rising tensions in Kansas compelled Brown to go to the aid of the anti-slavery settlers there, including five of his adult sons. Pro-slavery forces known as “Border Ruffians” interfered with voting, imprisoned abolitionists, harassed free settlers, and eventually seized the town of Lawrence.

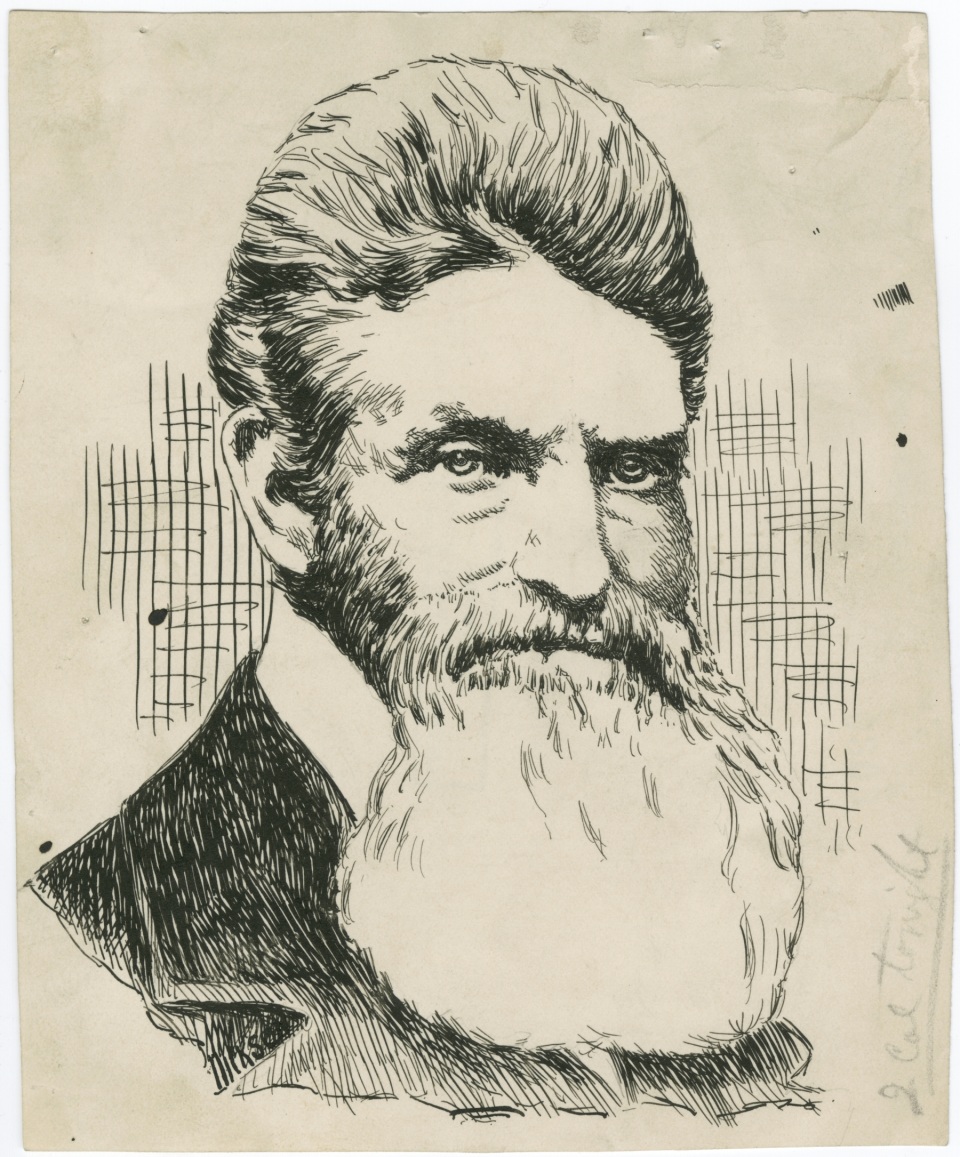

This photograph shows a rather more dapper John Brown than the later images and drawings, in which he appears disheveled and heavily bearded. He moved his large family ten times between 1825 and 1855, during which he was a devoted abolitionist and member of the Underground Railroad. As a failed businessman, Brown worked odd jobs while advocating for the end of slavery.

Photograph of John Brown, circa 1850. Portraits Collection, Prints and Photographs, Library of Virginia.

On 24 May 1856, Brown led a small group of armed men against their pro-slavery neighbors at Pottawatomie Creek, killing five. This catalyzed a civil war in Kansas, and created the public image of “Osawatomie Brown”—a nickname awarded for Brown’s heroic, if unsuccessful, defense of an anti-slavery settlement—as a recipient of both admiration and hatred.

This engraving from Frank Leslie's Weekly shows the Storming of the Engine House at Harper's Ferry. When the town's militia surrounded John Brown's force, they made their last stand at the railroad engine house, afterwards known as John Brown's Fort. Ten of Brown's men were killed, including two of his sons, and seven with captured and tried with Brown.

Frank Leslie's Weekly, Oct 29, 1859. Special Collections, Library of Virginia.

Brown raised funds based on his new-found notoriety, trained his men, and planned their next move—the Raid of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. On 16 October 1859, John Brown led 18-men—13 whites and five blacks—into Harpers Ferry. The plan was to seize the 100,000 rifles in the federal armory, arm local slaves, and march south, fighting only in self-defense. Brown’s men seized the armory with little trouble. However, things went awry when a free black man working as baggage master attempted to warn an incoming train of the danger at hand. Sadly, he was shot by Brown’s men. After the death of the baggage master, Brown allowed an eastbound to leave Harpers Ferry and spread word of the raid. Rather than the army of freed slaves for which they hoped, the pro-slavery forces began to gather. When the town’s militia surrounded John Brown’s force, they made their last stand at the railroad engine house, afterwards known as John Brown’s Fort.

On 18 October, United States Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee stormed the engine house. Ten of Brown’s men were killed, including two of his sons, and seven were captured and tried with him.

Media coverage of the failed raid showed the idyllic town of Harpers Ferry, where order was swiftly restored by federal troops, and portrayed John Brown as a fiery-eyed idealist, sympathetic in his advanced age and unshakable faith. Severely wounded and taken to the jail in Charles Town, Virginia, John Brown stood trial for treason against the commonwealth of Virginia, for murder, and for conspiring with slaves to rebel. On 2 November, in a mere 45 minutes, a jury convicted him and sentenced him to death. Brown readily accepted the sentence and declared that he had acted in accordance with God’s commandments. Responding to persistent rumors and written threats, Henry A. Wise, governor of Virginia, called out state militia companies to guard against a possible rescue of Brown and his followers. On 2 December 1859, Brown was hanged in Charles Town.

After the execution, Brown became a divisive figure in national politics. Southerners rejoiced in putting down a violent rebellion while Northerners tolled church bells for a martyr and won more converts to the abolitionist cause. Governor Wise, whose records are housed at the Library of Virginia, received multiple threats from enraged, anonymous citizens which can be viewed on the Abolitionist Map of America as well as the Library of Virginia’s Death or Liberty exhibit. Publications such as Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly replayed the drama in American households. Broadsides for vigils or community organizing demonstrate the far-reaching effects of John Brown, better seen through the use of mapping technologies on the Abolitionist Map of America. These events polarized the nation, making John Brown’s campaign a success in the long view.

This broadside asked all true Christians to pray for John Brown, who was to be hung next month for righteousness sake, and doing justly with his fellow man, his country and his God. Unlike other armed revolutionaries, Brown inspired empathy through his highly spiritual writing from his jail cell and published in the Northern press. Many identified Brown's decision to die as a martyr to the cause--he had opportunity to escape and did not take it--as Christ-like in its display of conviction. Published in Somersworth, New Hampshire.

Treason Broadside, 1859 November 4. Gov. Wise Executive Papers, Library of Virginia.

The moral conflict between freeing slaves and the shocking violence Brown committed continues to make him a compelling historical figure. How would we react to this type of principled violence today? Freedom fighter or terrorist?

-Sonya Coleman, Digital Collections Assistant

Editor’s Note:

To learn more about the Library’s involvement with the Abolitionist Map of America, see Sonya’s previous blog post.

To learn more about records related to John Brown’s raid at the Library, see John Brown’s Raid: Records and Resources at the Library of Virginia.

Just can’t stand to read about this vicious man who placed himself in the status of “God”! Otherwise, I absolutely love your site!!!!!

Really. So Despite the Times “Allowing” or “Condoning” Slavery, as a Human Being it’s Paramount that one must Do what is Right. God Status ? How about Generals’ on the Civil War Battlefield “Ordering” Men – Boys – To their Death knowing it’s Suicide – Or Murder ? If Trying to Free other Men is placing yourself in that position – So be it. Think of this, YOU may be the closest to God – Or Christ – that some people may EVER have. Doing what’s right will be the prevailing belief

His soul is marching on! https://soundcloud.com/user660132316/glory-glory-john-brown-tribute

John Brown used extreme measures with hopes of resolving an extremely oppressive social issue. He was regarded by many of his time as a mad man, but he lived by strong convictions of justice, freedom and human rights. When John Brown talked with another anti-slavery advocate, William Lloyd Garrison, he posed a simple question: How many slaveholders have freed their slaves after 20 years of abolition work? While championing nonviolence towards a brutal class of people (slaveholders), an entire generation of enslaved Afrikans continue to suffer an extreme disregard of their humanity, many suffering instant death for minor infractions of insubordination, or even hints of insubordination. Either Afrikan life has value or it doesn’t. If only white life have value, then John Brown was wrong. But if ALL life has value, then John Brown is to be commended for pushing the envelope, which also accelerated the struggle around slavery and its abolition.