While watching the February 2012 episode of NBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? featuring actor and Petersburg native Blair Underwood investigating his family history, Library of Virginia staff could not help but notice that one of the original volumes displayed on the show was not in great shape. The Amherst County Register of Free Negroes, 1822-1864, was used on the show to prove that one of Underwood’s ancestors had been a free person prior to the Civil War. The front and back covers of the volume had become detached from the spine, pages were loose, and overall it did not look like the book could withstand much handling without sustaining further damage to its fragile pages. This led to a reevaluation of the existing conservation priority for the 30 free Negro registers in the Library’s holdings. Previously it was thought that since all of the free Negro registers were microfilmed, the original volumes would not be handled by the public any longer, thus conservation money would be better spent on other items. However, the resurgence of interest in African American genealogy, the sesquicentennial of the Civil War and related issues, and interest in the registers for display in exhibits clearly indicated that a change was necessary. A conservation inventory was done for all of the volumes and the ones that require treatment will receive it over time and as funds allow.

So what is a free Negro register and why do they exist? In 1803 the Virginia General Assembly passed an act that required every free Negro or mulatto to be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the county clerk. The register listed the age, name, color, stature, marks or scars, and in what court the person was emancipated or whether the person was born free. A free person was required to carry a copy of this register on them in order to prove their free status. It was a criminal offense to not be registered, and a free person could be sold into slavery if they were unable to produce sufficient proof of their status. Enforcement of these laws was done locally and could be inconsistent. Times of great societal fear about a locality’s black population would often result in an increase in both registrations and prosecutions for being unregistered—for example, following Nat Turner’s uprising. The free Negro registers were thus both instruments of control over the free black population of the state but also a safeguard of an individual’s free status should it ever be challenged. The registers provide wonderful physical descriptions of free people that give the researcher a real idea of what someone looked like, information often hard to come by for other groups of the pre-Civil War era. They are extremely important records for genealogists and have been used by historians for a variety of avenues of inquiry.

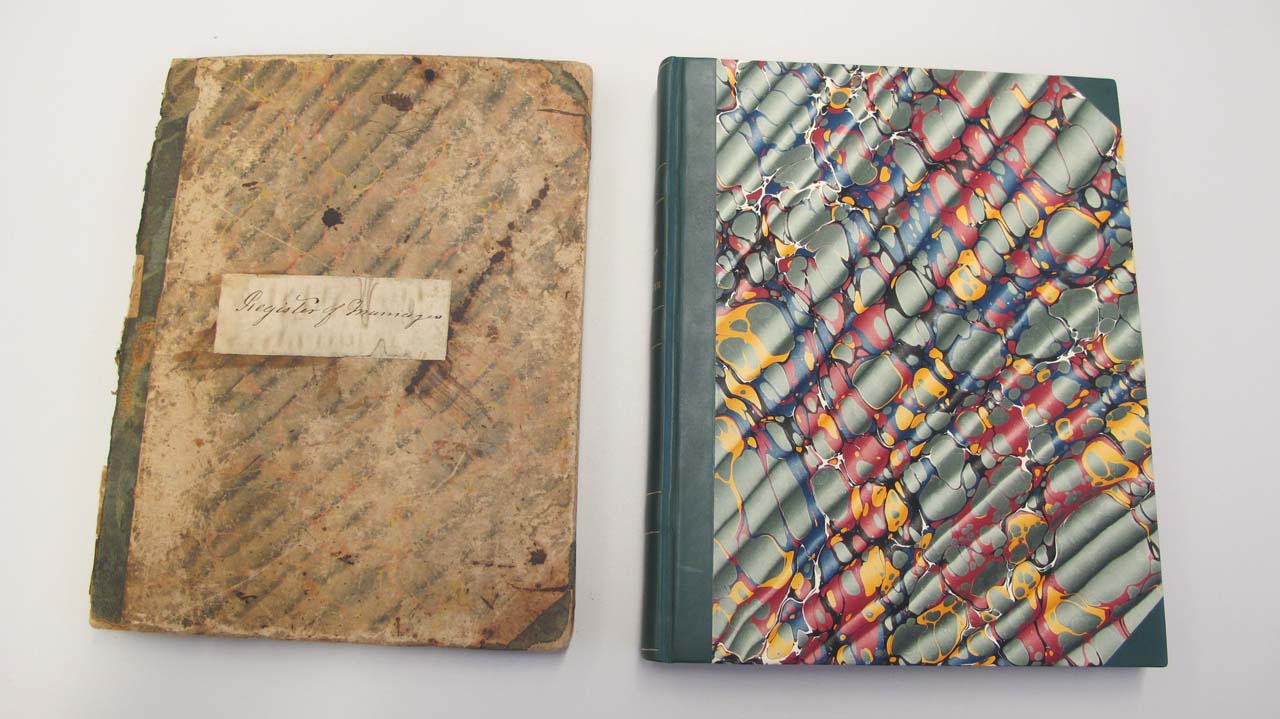

The first four volumes chosen for conservation were completed and returned to the Library of Virginia from Etherington Conservation Services in March 2013. Included among them is the Amherst County register from Who Do You Think You Are? The pages have been cleaned, mended, and deacidified. The original boards of the cover have been retained because they were still in good shape although they got a restorative touch-up with watercolor and pencil. The old leather bindings have been replaced with new leather. The other volumes are three registers from Amelia County that date from 1804-1835, 1835-1855, and 1855-1865. These registers all had broken bindings, loose or completely separated covers, and loose pages. As the pictures show, the conservators completely replaced all of the covers and bindings on the Amelia registers. The new bindings and board cover patterns were matched as closely as possible to the originals. All of the pages of the volumes have been cleaned, mended, deacidified, and resewn into their new bindings. The Amherst and Amelia free Negro registers are now ready for their Hollywood close-ups! These registers still will not be available to the general researcher since copies exist on microfilm, but their conservation will ensure that these important volumes are preserved for future generations, and, when they are needed for a special display purpose, that they are in a physical state to withstand such handling and exhibition.

Conservation of archival records, maps, and books is expensive and takes time to do properly. Treatment done right extends the life of the record by slowing down or reversing damage to paper, bindings, and leather while at the same time being reversible and not a permanent alteration to an item. Stay tuned for future conservation updates about free Negro registers and other interesting records within the Library of Virginia’s holdings.

The Library of Virginia welcomes donations to our general conservation fund in any amount. Interested in sponsoring a particular book or item? See suggestions on the Adopt Virginia History page.

-Sarah Nerney, Senior Local Records Archivist

What will it cost to restore one of the bookson Free Blacks?

Thanks for reading the blog and for your interest in the Library’s conservation efforts. It would cost between $1300-$1900 to restore one of the free Negro registers, depending on the volume’s condition and size. If you’re interested in sponsoring a particular item, see the Adopt Virginia History page here — http://www.lva.virginia.gov/involved/adopt.asp

Thanks for commenting!

The information about slavery seems to be never ending. I am anxious when Black American students do not have access to this knowledge about their heritage. I think it would make a difference in how they value themselves.

Fantastic! I am so happy this was done. Thanks for sharing.

I’m curious about the Moore families of this area.

I was recently in the Accomack County, Va, library and clerk’s office (from out of state) trying to find a slave trail. Some of the books were falling apart, unreadable and what was on the ancient Microfiche really didn’t help. The staff was very helpful though. There wasn’t even a bathroom in the clerk’s building!

It was a totally different story up the road in Somerset County, Md. Some of their documents even had metal covers and all were in great condition.

With slavery being so difficult to research as it is, having intact documentation should not be optional. It was appalling to see that no funding has been prioritized in Virginia for such historical preservation. Plus, research can take hours and a public bathroom in the bldg is a requirement, let alone for the staff!

For Maryland research I am able to even look up land records online for free. I have found quite a bit online in Virginia too but eventually a trip to the courthouse and library is required.

Ms. Norma,

Since 1992, the Virginia Circuit Court Records Preservation program, administered by the Library of Virginia, has provided over $20 million in grant funding for records conservation, preservation, and access. Circuit Court Clerks from Virginia’s any of the Commonwealth’s 133 localities can apply for funds to support item conservation, digital reformatting, and other preservation efforts. The program is outlined at http://www.lva.virginia.gov/agencies/CCRP/

As to restroom access, while we are sorry for your inconvenience, the locality is solely responsible for the facilities available at its building.