Editor’s Note: This post originally appeared in The Delimiter, the Library’s in-house on-line newsletter. It has been shortened and edited slightly.

This week Out of the Box would like to spotlight the records of the Virginia Prohibition Commission, 1916-1934 (Accession 42740). The collection contains 203 boxes of paper and two volumes spanning nearly 20 years. The records provide valuable insight into enforcement of Prohibition laws in Virginia, as well as a glimpse into significant societal changes occurring at that time. Yet, this valuable resource was nearly lost to generations of researchers. In 1938, a bill was submitted to the House of Delegates seeking to destroy the records; however, the editors of the Richmond Times-Dispatch and citizens of the community strongly protested that these records should be preserved.

A bill was eventually passed transferring custody of the records of the Prohibition Commission to the State Librarian “to preserve such of the records and papers as he may be of the opinion should be preserved for historical or other interest.” The Library of Virginia processed this collection in 2010.

The Virginia Prohibition Commission was created in 1916 by an act of the General Assembly to enforce the Virginia Prohibition Act, which went into effect on 1 November 1916. This law did not restrict individuals’ ability to manufacture alcoholic beverages, or “ardent spirits,” for their own use, but did restrict the sale and transport of said goods. In 1918, laws concerning Prohibition were clarified and altered under the Mapp Prohibition Act, which now outlawed the manufacturing of spirits. When the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1919, the role of the Prohibition Commission changed yet again. The Commission afterwards operated in conjunction with federal officials, although the main responsibility for enforcing Prohibition laws remained with the Commission.

The Commission’s records provide a glimpse into this fascinating period in American history. The Inspectors’ Reports series contains evidence of the work done in the field by the full-time and volunteer inspectors throughout the state. It is through these records that the changing role of the inspectors can be seen. From 1916 until the Mapp Act went into effect in 1918, the main responsibility of the inspectors was to monitor railways and waterways to uncover smuggling of “ardent spirits” into Virginia.

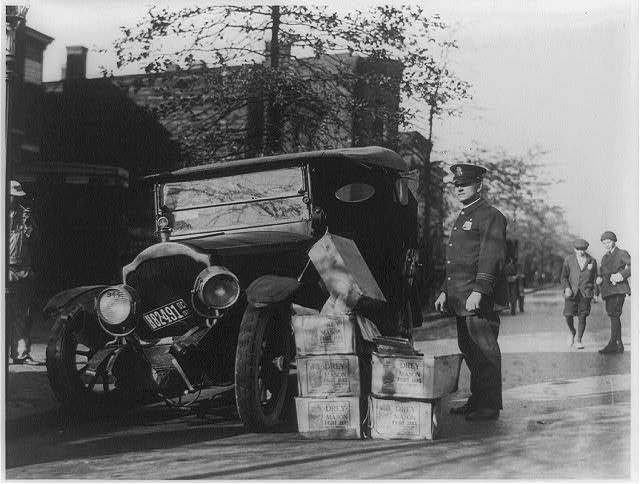

Once the Mapp Prohibition Law took effect in 1918, the role of the inspector changed, becoming the prototype of the “revenuer,” pursuing lawbreakers attempting to produce alcohol. For many years, the names of individuals arrested for Prohibition violations were published in the Commission’s annual report, along with the fines imposed, and amount of jail time, if any. In 1926, Don Early was arrested in the suburbs of Galax for “selling extracts for beverage purposes” – the report stating that Early was hiring teenage boys to purchase cases of vanilla extract at a wholesale grocer in Galax. He was fined $50 and costs. Mrs. Ola Rickman was arrested for possessing a still and mash in 1930 in Botetourt County. According to the report, “this still was in a secret basement there being a box over a trap door leading from a room in the house.” Rickman was released on $500 bond with a court date to follow. Further, Mr. R. V. Johnson of Richmond was arrested for possession of stills and liquor on Epps Island in Charles City County in 1928. The estimated value of the goods seized was $5,000 and included two wood and steam stills, 500 gallons each; one 10-horsepower upright steam boiler; eight 500-gallon fermenters, and four large boats. Also found in the raid were 9,000 gallons of mash and 155 gallons of “ardent spirits.” Johnson was immediately incarcerated in the Henrico County jail. In addition to highlighting the types of violations the inspectors uncovered, there is evidence in the reports of new technologies being used in the building of stills, and techniques used to evade inspectors. For example, the value of the seized goods in the case of Johnson is very high, due in large part to his use of a steam boiler. In another report, there is mention of a vehicle employing a “smoke screen device” in an attempt to elude inspectors.

The Transportation Permits series yields a surprising wealth of information on the medicinal use of alcohol and shifts in business practices and society. Prior to the ratification of the 18th amendment, Virginians could, for 50 cents, secure their own transportation permit for the acquisition of medicinal whiskey – with an accompanying prescription. While the majority of the reports contain stock requests for “ardent spirits” for mechanical, medicinal, sacramental or scientific purposes, some requests provide atypical justifications for needing alcohol. Among those who applied for permits was Confederate veteran W. C. Sanders of Wytheville. Major Sanders was wounded in 1864 at Piedmont in Augusta County, sustaining a chest wound that penetrated his lungs and exited his back. Initially thought to have sustained a mortal wound, a local citizen, Mr. Crawford, observed that Sanders was still alive. According to an account in the Richmond Journal, Crawford “poured into the Major half a pint of mountain whiskey, which stimulated his heart and lung action and led finally to his recovery.” Major Sanders wrote regularly until his death to the Commission for a transportation permit for his medicinal whiskey, and enclosed a photograph for the Commissioner, detailing his story.

Medicinal whiskey or other spirits also could be obtained from the Prohibition Commission itself. In October 1918, a prescription for medicinal rye was sent to the Commission for the treatment of influenza, during the flu epidemic. There are many references in this series to the flu epidemic, since the treatment was often whiskey (or rye, in this case), which necessitated securing a transportation permit from the state. Requests from women for alcohol to use in their medical practices in the mid-1920s are evident. One businesswoman requested permits for using alcohol in baking and making preserves.

Upon passage of the National Prohibition Act in 1919, the issuing of permits became subject to federal regulations. Those opposed to Prohibition were vocal, as evidenced by the letter received by the Commission in 1919 from Dr. F.C. Tice. Dr. Tice writes “As the curfew hour for all time approaches and I expect to practice for at least ten years yet, I am more than perturbed at the prospect from a medical standpoint.”

Defiance of the law often came from unlikely people. In 1924, Dr. J.W. Witten of Tazewell County, a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, responded to a letter from the Commissioner (obviously a personal friend) “Come up and help me drink this it ought to be good, been two years getting it.” According to the permit, Dr. Witten received 1½ gallons of whiskey for medicinal purposes.

The end of Prohibition came in stages, with the legalization of the sale of beverages containing not more than 3.2 % alcohol by weight in April 1933. At that point, beer became legal and the quantity of transportation permits requested increased dramatically. Requests for transportation permits were even composed on stationary provided by the breweries, such as the one from Perkins Cut Rate Drug Store in South Boston. The permits were issued for 50 cents – and every permit stated the items being transported were for medicinal purposes. After the repeal of the National Prohibition Act in December 1933, the Prohibition Commission continued to function, regulating the transportation of alcohol within Virginia, until March 1934 when the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board was formed.

The Virginia Prohibition Commission Records are open for research and can be accessed in the Archives Annex Reading Room at the State Records Center.

The Archives Annex Reading Room is open on Wednesdays and Thursdays, 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM and 1:00 PM to 4:30 PM. The building is closed during the lunch hour. Researchers should consult with the Archives Reference Services staff about materials housed there and call 804-692-3888 in advance to schedule an appointment. Researchers must register to use the room and follow the same policies as govern the use of materials in the Archives and Map Research Rooms at the Library of Virginia. State Records Center Directions

Laura Drake-Davis, former State Records Archivist

One Comment