In the late 1880s and early 1890s, Southwest Virginia was gripped with “boom” times as the Norfolk & Western Railroad opened up the region for development. Small towns and even previously non-existent ones exploded with growth seemingly overnight. Land development companies swooped in, mainly with northern capital, to carve up farmland into future cities. Montgomery County was no stranger to this concept as the “boom” swept through its borders. Central Depot at the far western edge of the county had been a small railroad community, but by the 1870s and 1880s, developers started devising ways to make it grow. The community would go on to become Central City as a fully incorporated town, then Radford, and then the independent City of Radford.

A group of chancery records from Montgomery County bear witness to the “boom,” or more accurately to its aftermath, as the bubble burst on dreams for development. These cases, W.R. Liggon vs. George W. Tyler etc., T.E. Buck vs. George W. Tyler etc., and Nancy M. Liggon etc. vs. George W. Tyler etc. (1897-056) and R.B. Horne etc. vs. George W. Tyler etc. (1897-057) give fascinating insight on the inner workings of “boom” times.

In this period of extraordinary growth for many towns, real estate speculation was the name of the game. Huge profits could be made by buying land, dividing it into lots, and reselling them. Each time the property sold, a profit could be made. Speculation was predicated on future development; however, the promised development did not always pan out. The bubble burst on the explosive growth of Southwest Virginia in 1893 as part of a larger nationwide panic, but cases 1897-056 and 1897-057 indicate the “boom” was cooling down in Radford as early as 1891. In the four suits filed against real estate partners George W. Tyler and George E. Cassel, the complainants sought to have deeds for the lots they purchased declared null and void on account of fraud so that Tyler and Cassel would be prevented from collecting further payments.

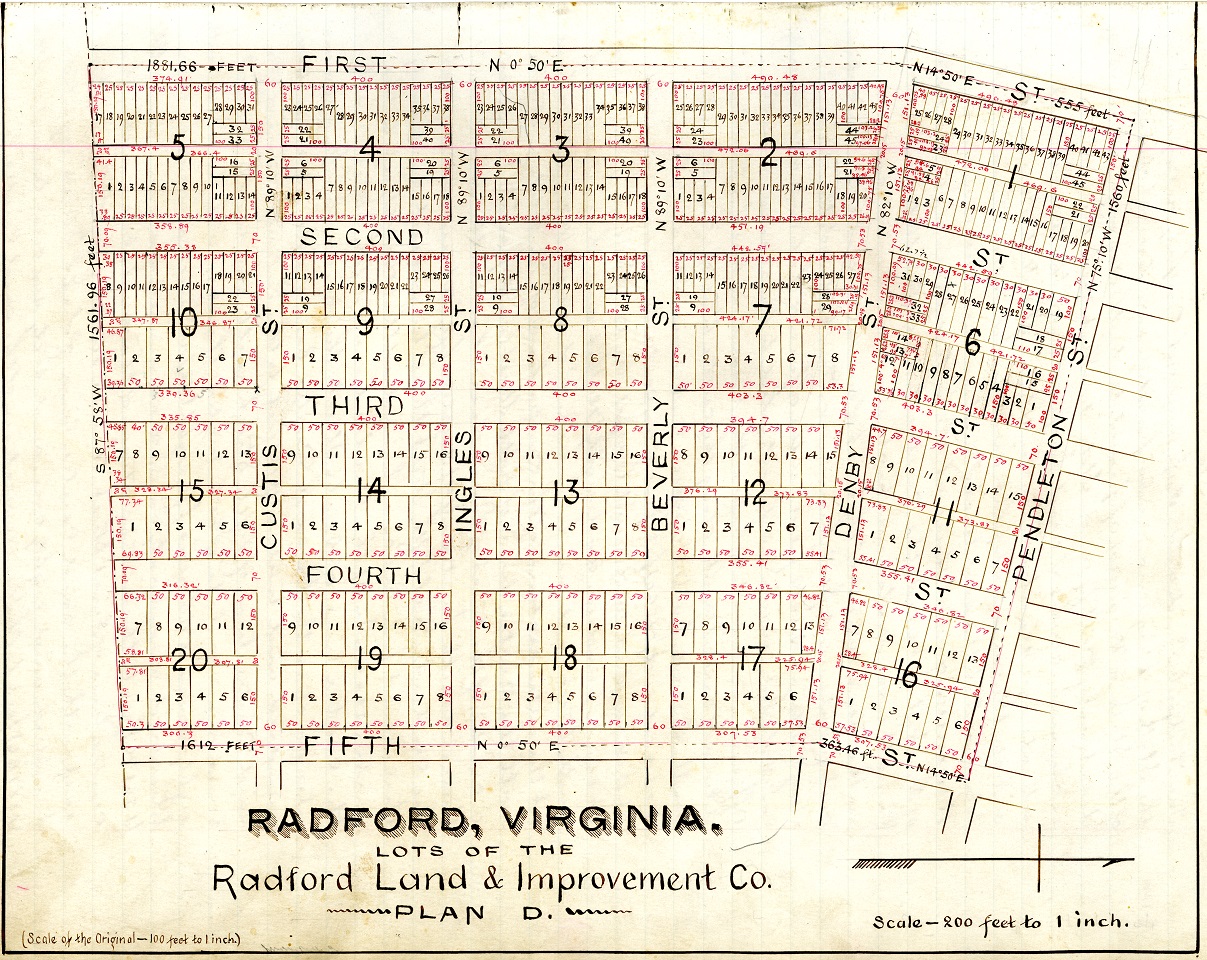

The journey made by the land in question in the suits shows how land speculation worked in the “boom” period. The deeds reveal that in 1890, the Radford Land & Improvement Company purchased 150 acres from William Ingles for the heavily inflated value of $33,750. The said company then divided the land up into a grid of streets, sections, and lots, calling it Plan D. William Ingles and other parties then purchased Sections 2 and 7 of Plan D for $16,000. Ingles then sold Section 2 to Tyler and Cassel for the sum of $23,333. Tyler and Cassel then sold over 40 lots in Section 2 for a total of $29,000, by Cassel’s account. All of this unbridled inflation was founded on the idea of tremendous growth and development. Unfortunately, for all parties concerned, the “boom” period came to a screeching halt. In Cassel’s own words, “the industry harvest is past and we are not saved.” The complainants were all left still owing on lots that were no longer nearly as valuable as when first purchased.

All of the complainants claimed that they purchased lots from Tyler and Cassel in Section 2 of Plan D with certain conditions being understood. First, that the said Tyler and Cassel would take care of the building restrictions placed on the land by the Radford Land & Improvement Company, which could leave a cloud over their title to the lots if left intact. Cassel and Tyler also promised buyers that they would construct business buildings in the section, which the buyers also believed would improve value. Second, all of the complainants attested that they were promised that new industrial concerns–such as an iron furnace that would employ many men, a new steel plant, and a nut and bolt factory–would come to Radford. Other improvements were to include a new rail line built along the Little River to access iron mines, and a streetcar system that would pass directly in front of Section 2. By the time the suits were instituted, these developments had not taken place, thus the claim of fraud.

Depositions from the cases provide interesting glimpses into Radford’s history and the functions of real estate speculation as witnesses spoke of the Radford Real Estate Exchange, which was part of the State Exchange. The account given by George E. Cassel showed that the Exchange’s goal was to sell land and also to induce industry to come to Radford. He mentioned how tracts at times were offered for free to interest manufacturers and promote more development. He also spoke of the fact that agents shared news with other members of the exchange to help spur growth. A fascinating concept was the way highly desired lots were handled. Agents had access to all lots to cover more territory; a chalkboard was on the wall of the Exchange to keep things in order. Two agents might sell the same lot, but the one who wrote it on the board first was the one who had the right to complete the transaction and earn a commission. The depositions reveal that lots could have a journey of many “owners” before finally being recorded. According to Cassel, “lots traded like stocks and bonds.”

At the conclusion of all these cases, the decrees show that only Nancy and Rosa Liggon resolved their issues with Tyler and Cassel. The rest of the cases were dismissed, with the complainants having to pay the defendants’ costs on top of what was still owed on the lots. These cases and many others like them show the pitfalls of “boom” times and real estate speculation.

The processing and indexing of the Montgomery County chancery causes, 1777-1912, which is currently underway, has been funded in part by a two-year grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). Additional information on this project can be found in an earlier blog post.

–Scott Gardner, Local Records Archival Assistant

Very Interesting! I am fascinated about the “chalkboard” on the wall of the Exchange!

Great post Scott Gardner. The “boom” played out in courts up and down the Shenandoah Valley. Thank you for sharing this story.