In my work for the Civil War 150 Legacy Project, I recently came across the diary of Aquilla Peyton (1837-1875). A private in the Confederate Army, Peyton was a young man with a loving family living near Fredericksburg, Virginia, and an avid diarist with a spiritual nature and a naturalist bent. Peyton kept this particular diary from August 1861 to August 1863. His final days as a soldier were in December of 1862; in January 1863, he returned home and recommenced teaching school.

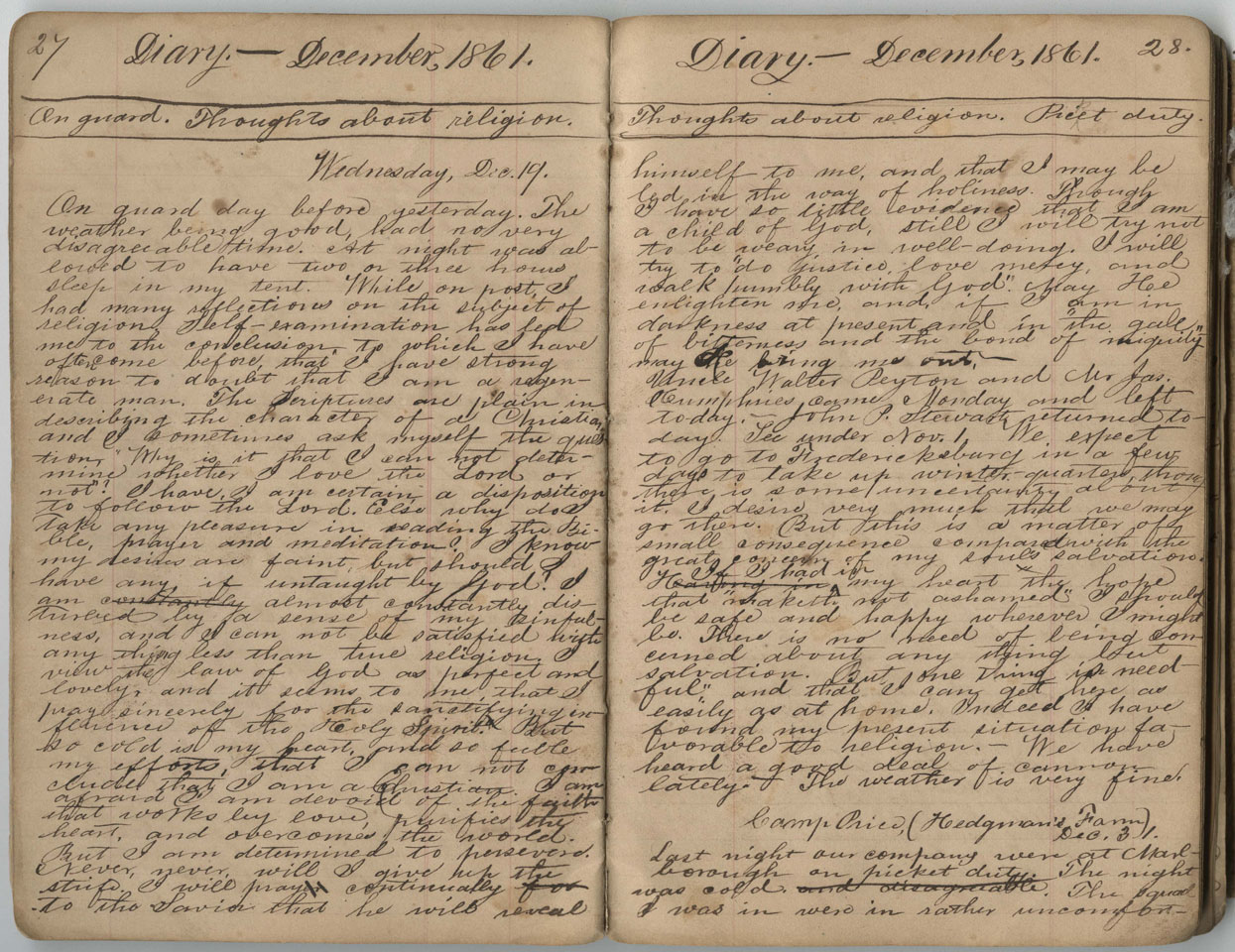

Peyton’s diary is quite long at 186 pages, and is teeming with quotes from the Old and New Testaments, daily logs on the weather and the changing of seasons, and achingly personal observations on the unworthiness of his character and his struggle to be a better Christian. On Wednesday, 19 December 1861, Peyton wrote:

I am

constantlyalmost constantly disturbed by a sense of my sinfulness, and I can not be satisfied with any thing less than true religion. I view the law of God as perfect and lovely, and it seems to me that I pray sincerely for the sanctifying influence of the Holy Spirit. But so cold is my heart, and so feeble my efforts, that I can not conclude that I am a Christian. I am afraid I am devoid of the faith that works by love, purifies the heart, and overcomes the world. But I am determined to persevere.

Despite his fears to the contrary, Peyton seems to be quite devout, with a profound knowledge of the books of the Bible—indeed his diary contains nearly a hundred short Biblical quotes, and longer multiple-chapter passages. His relentless self-scrutiny is an indication of the acuity of his mind, which is further revealed in the precision of his language. When at first he writes “I am constantly disturbed,” he immediately alters his words, stating instead that he is “almost constantly disturbed.” His need to be absolutely clear, completely accurate, and utterly transparent in his diary entries is quite touching.

Peyton struggles with his passions, and appears to be very conflicted and tormented regarding his “baser” desires. Rather than attempt to justify the quenching of his thirst and hunger as a necessary desire, Peyton refuses to operate under any scale of relativity, believing his daily actions must only and always exist to serve God.

I really make myself a great fool about my belly. Not only do I give way to needless anxiety about necessary food, but even when I have eaten enough I feel a disposition to indulge further, and am almost always on the look-out for something to please my appetite. This devotion to the pleasures of eating is a mighty hindrance to me to the performance of duty. What I desire to feel is comparative indifference to this matter; to have such a sense of the infinite superiority of spiritual food and drink, and such a hungering and thirsting after righteousness, as to care little about the quantity and quality of my food (2 September 1862).

This over-arching abasement of self in order that the love and service of the Creator remain paramount is foundational no matter the topic Peyton treads. Throughout his passages regarding the wonder of the natural world, he never ceases to attribute its elements solely to God, thereby requiring of himself that any enjoyment he feels be solely in connection to his worship.

To me it is the source of exquisite pleasure to be alone among the tall trees. The aspect of things around calms the mind, and brings again joyous sensations that were felt years ago. It is an agreeable consideration to me that man did not make the trees. He may own them, but there is a majesty and beauty about them that speaks of the mighty power and skill of God, and exalts them, in a sense, above man. I do love nature in all her aspects. I have thought that my fondness for her amounted almost to idolatry (2 September 1861).

This abiding devotion to God does not render Peyton myopic, however. His entries are resplendent with exclamations regarding his natural surroundings, covering the color of honeysuckle, the types of trees found in the woods in which his company camps, and the variety of berries he savors.

The woods near our camp have some sweet paths for those who are fond of lonely walks. I belong to that class. I love to be alone in the coolness and quiet of the green wood. “How strong the chain that binds our affections to earth!” thought I this morning, as I turned into one of these paths and thought how dear the old woods at home were to me, in which I have had so many pleasant rambles. “These woods,” thought I, “are fully as beautiful and pleasant as those at home, except in one essential particular: they are not at my home” (17 June 1862).

Peyton’s writings tend to remain focused on the personal and the spiritual; when he does write of his daily duties as a private in the Confederate army, he hovers around the material, physical aspects of his routine, rather than the militaristic or partisan particularities of life as a hungry, peripatetic soldier. Throughout, he holds an abiding loyalty to his home state:

The face of nature here is lovely now. It is sweet to view the fresh young foliage of the trees, and to hear the songs of the birds. But there is no superiority to Virginia’s charms of nature (2 May 1862).

He does speak of the “foe,” and the various incursions and skirmishes, but his focus on the nature of existence, the struggle to make life spiritually significant, and the beauty found in the everyday render him–to this reader–as a poet of the highest order. For me, his most beautiful passage is the following, a kind of timeless call to action–or to thought: “Was struck this evening with the thought that the troubles of life would be immensely lessened by living one day at a time, according to the precept, ‘Take no thought for the morrow’” (21 June 1863).

You can find Aquilla Peyton’s diary online at the Civil War 150 Legacy Project page on Virginia Memory.

-Jennifer Rogers, CW 150 Project Archivist

I have the original diary. I was given it by the Swecker/Zwecker part of my family. I am trying to find out how this “cousin” relates to the Sweckers.