Recently I stumbled upon one of the more interestingly-worded government documents that I have ever encountered. Housed in the papers of Confederate soldier G.B. Lamar, Jr., of Georgia, was a leather-bound “passport” dated 1867. But this wasn’t just any ole’ passport–embossed in gold letters on the book’s cover were the words:

Hand Book of Loyalty.

Passport for Any-Where.

Being a holder of a passport myself, and thereby glancingly familiar with the process of attainment and the general requirements of such, I couldn’t believe that such fanciful language could accompany something heretofore seen as banal and utterly devoid of hyperbole or flights of fancy. But–here it was! A passport to anywhere!

One might argue this is just a statement of the obvious, for a United States passport is, clearly, a document allowing one to travel “anywhere.” Yet the language trumpeted on Lamar’s leather cover hints at possibility and adventure in a way that my prosaically blue passport vehemently does not.

To open the book is to be confronted with yet more extravagant jargon, for it announces these intentions:

To produce the most

Soothing Feelings of Patriotism

In the Shortest Space of Time.—Works like Magic.

It turns out this was not a passport per se, but a wryly humorous book for former Confederates who had, perhaps reluctantly and out of pure necessity, sworn their allegiance to the United States after the war.

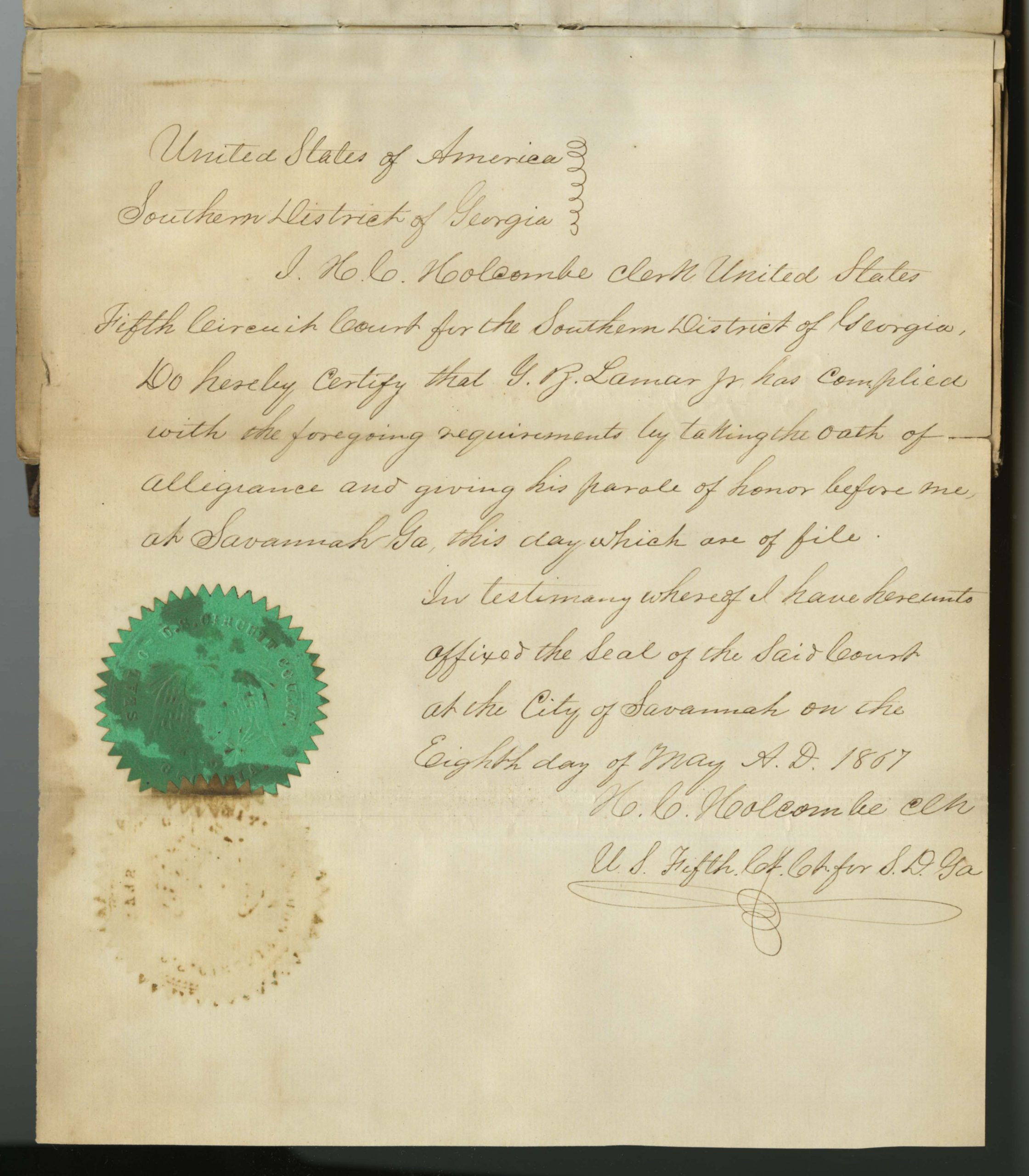

Inside, Lamar had pasted several copies of certifications and signatures–his oath of allegiance to the government of the United States and his pardon of honor. These papers were indeed a required “passport” of sorts in the post-war South, but not the type with which we are familiar today.

Be that as it may, my curiosity was piqued and I began researching the history of the passport in the United States. The term itself is of French origin, and refers to a literal “passing through a port.” The earliest versions of the U.S. passport were issued in the late 18th century, yet the modern passport requirement for traveling U.S. citizens did not begin until 1941. However, for periods during the Civil War and World War I they were temporarily mandated for any travel; in the former case they were often used for travel domestically. As might be assumed, the average traveler or passport holder during the 19th century was male and white. Women were “allowed” to travel, yet their documents generally held the name of their fathers or husbands. Leading up to and during the Civil War a “special passport” was issued to free persons of color, however I am ignorant of the acceptance of such papers in the various Confederate states.

Where exactly did G.B. Lamar, Jr., go after the war? It’s likely he just went back home to Georgia. Alas, this “Passport for Any-Where” probably did not help much if he had dreams of visiting parts unknown, exotic, arctic, or tropical…even Canada. Perhaps we’ll never know…

The G.B. Lamar Papers, 1859-1867, were scanned as part of the Civil War 150 Legacy Project, and can be accessed by searching keyword “Lamar” on the project’s page on Virginia Memory.

-Jennifer Rogers, CW150 Project Archivist

Note: Some information used in this article was found in Galliard Hunt’s The American Passport: Its History and a Digest of Laws, Rulings and Regulations Governing Its Issuance by the Department of State (1898).