This is the first in a series of four blog posts related to the “To Be Sold” exhibit which opens on October 27 at the Library of Virginia. Each post will be based on court cases found in LVA’s Local Records collection and involving human traffickers. These suits provide insight into the motivation of individuals to get into the business, as well as details on how they carried out their operations. Even more remarkably, these records document stories of enslaved individuals purchased in Virginia and taken hundreds of miles away by sea and by land to be sold in the Deep South. The following narrative comes from Norfolk County Chancery Cause 1853-008, Thomas Williams vs. William N. Ivy, etc.

In 1838, Thomas Williams and William N. Ivy formed a partnership “for the purchase of slaves to be sent to Louisiana.” Their plan was to first hire out the forced laborers for about a year to local businesses, then to divide between them the wages earned by the enslaved individuals and a free African American they employed as an apprentice. Once the hiring-out period ended, the individuals would be sold, or “disposed of” as Williams called it, for a profit. To finance their venture, Williams and Ivy received a loan of $5,000 from the Exchange Bank of Virginia at Norfolk. Ivy left for Louisiana to make arrangements for the arrival of the enslaved individuals, leaving Williams in Norfolk to purchase them.

On 30 October 1838, Williams purchased three enslaved persons: Jack, age 27, from James Freeman of Norfolk, Virginia, for $765; George, age 23, from Allen G. Buxton for $800 and Elizabeth (also known as Lizzy or Betsey), age 13, for $450 from John Gormley of Norfolk. On the day they were purchased, the three enslaved individuals were shipped to Louisiana on the schooner Choctaw and reached Louisiana in the latter part of November. Also put on the ship by Williams was the free African American apprentice–Mills Hamblin, age 16.

Williams purchased two additional enslaved men, William (Bill) White for $1,000 from William C. Burruss of Kempsville, Virginia, and William (Bill) Shepherd for $700. Both were placed on the schooner Pelican on 28 January 1839 bound for Mobile, Alabama. From there, they were shipped to the port of Franklin in Louisiana arriving in late February.

The four enslaved males and the free African American teenager were hired out to Daniel Sanford & Company, which had a contract with the Navy to cut timber located on Cypress Island. The enslaved men and Mills Hamblin had a difficult time learning the timber trade. According to Ivy, Hamblin was “totally unaccustomed to the business of timber getting and could never be usefully employed except as a cart boy.” It should not have been surprising to Ivy given that Hamblin originally had been apprenticed to learn the trade of farming, not timber. And, prior to being sold to Ivy and Williams, William White was an apprentice for a blacksmith. Consequently, the five earned lower than expected wages which cut into Ivy and Williams’ profit. The profitability of the partnership took another major blow with the death of the most valuable of the enslaved men, William White. According to Ivy, William White “unfortunately drowned” on 9 May 1839, when a boat he was in on Atchafalaya Bay capsized in a storm. His body was found two days later and was buried.

In the spring of 1840, “serious difficulties and embarrassments” committed by Ivy as manager of the Louisiana operations led to a lawsuit between him and Daniel Sanford & Company. Ivy lost the court case and was forced to sell Jack, George, and William Shepherd as well as the remainder of Mills Hamblin’s term as an apprentice. The men were taken 50 or 60 miles by steamboat from Cypress Island to the county jail in the town of Franklin where they remained 20 days until sold: Daniel Fisher purchased Jack and William Shepherd for $800 each. George was sold for $950 on 22 August 1840 to Martin Demaret, “a Frenchman.” Hamblin completed his apprenticeship term and returned to Norfolk.

Ivy’s mismanagement of the Louisiana operations brought an end to the short-lived Ivy and Williams partnership. Upon learning of Ivy’s legal troubles in Louisiana, Williams filed a chancery suit in Norfolk County against Ivy asking the court to settle the accounts of the partnership to determine what was owed to Williams. Both Williams and Ivy provided the court with documentation related to the purchase, transportation, hiring, and sale of the enslaved individuals. Exhibits filed in the suit include bills of sale, receipts, accounts, depositions, affidavits, and transcripts of cases involving Ivy heard in Louisiana courts. Despite the fact that they were not participants in the suit, the enslaved individuals had a prominent role in it. Surprisingly, the majority of the exhibits and testimony in the suit have to do with the 13-year-old enslaved teenager named Elizabeth. Her story will be told in next week’s blog.

Thomas Williams vs. William N. Ivy, etc., 1853-008, is part of the Norfolk County Chancery Causes, which are available for research at the Library of Virginia. The processing of this collection was made possible through the LVA’s innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP) which seeks to preserve the historic records of Virginia’s circuit courts.

-Greg Crawford, Local Records Program Manager

Header Image Citation

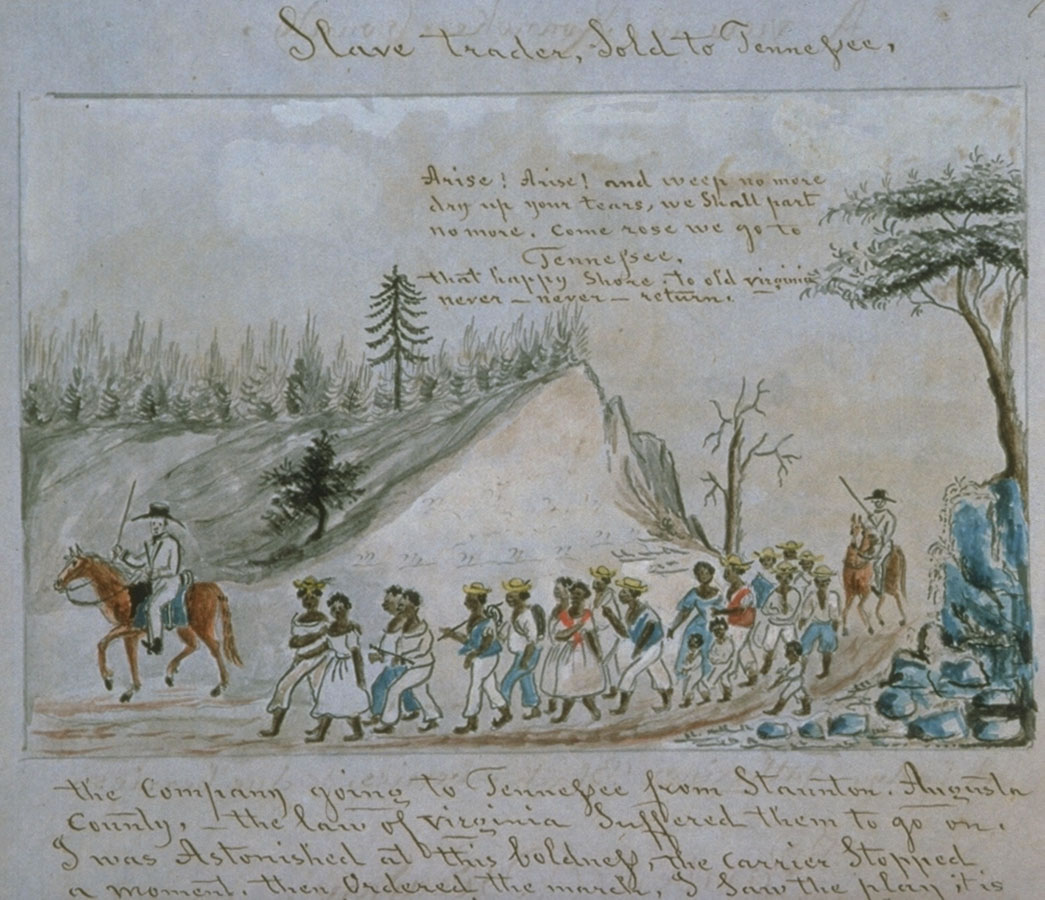

Illustration of Virginia slaves being sent South. Courtesy of/Posted by http://usslave.blogspot.com/2012_03_26_archive.html