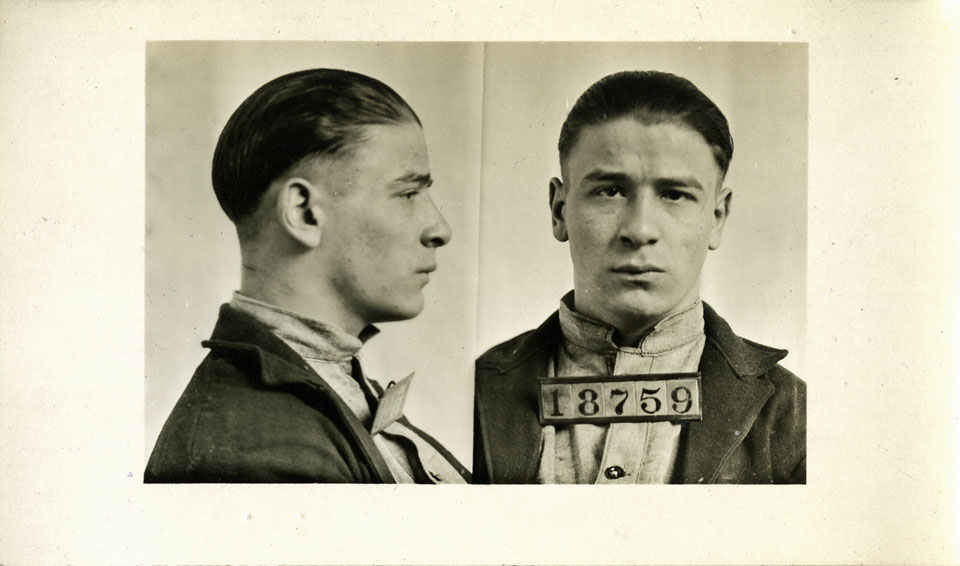

This is the latest in a series of posts highlighting inmate photographs in the records of the Virginia Penitentiary. Benjamin Liverman, the “Boy Bandit,” the subject of this week’s post, was first arrested at the age of ten. By the age of 17, he had a lengthy criminal record. His life of crime and the beginning of his reformation began in Norfolk in 1923 when he was convicted of robbery and sentenced to 53 years in the penitentiary.

Benjamin Liverman was born Donatto Siravo on 28 February 1905 in Fall River, Massachusetts. The son of Italian immigrants, Siravo did not have a good home life. According to the Massachusetts Department of Corrections, Alfred Siravo, Donatto’s father, worked as a weaver in Fall River. He was “quick tempered and very emotional and is blamed for much of the [couple’s] marital troubles.” In September 1915, Siravo, only ten years old, began his life of crime when he was arrested in Fall River for trespassing. Over the next six years, Siravo, still a minor, was arrested nine times and served time in the Lyman School for Boys and the Shirley Industrial School. He escaped the Shirley Industrial School on 9 January 1922 and made his way to Norfolk, Virginia, by November 1922. Over the next two months, Siravo, using the alias Benjamin Liverman, committed at least 15 crimes of burglary, robbery and attempted robbery. He was caught in February 1923, convicted in March 1923, and sentenced to 53 years in the Virginia Penitentiary.

As Virginia Penitentiary Superintendent Rice M. Youell later noted, Liverman’s lengthy sentence made him “very bitter and determined to escape if there was any way possible for him to do so.” It didn’t take Liverman long to try. On 14 July 1923, Liverman disappeared from the print shop where he was employed as a linotype operator. Penitentiary officials, believing Liverman was hiding, conducted a thorough search of the prison but did not find him. Not convinced that Liverman escaped, Youell posted extra guards and kept the searchlights on all night. Youell also patrolled the prison wall area for part of the night. After three nights, Youell set a trap. He turned off the search lights with the hope that if Liverman was hiding in the Penitentiary, he would try to escape during the night. The extra guards remained. Liverman took the bait, and much to the chagrin of Youell, successfully escaped sometime in the early morning of July 17. Liverman had hidden himself in the mud and water underneath the floor of the carpenter’s shop. With the search lights off, Liverman used a rope and ladder from the shop and scaled the wall. His freedom was short-lived. Liverman was recaptured at the home of his girlfriend in Petersburg later that day.

Liverman remained “very bitter” for several years. He was punished in September 1923 for “impudence” to Superintendent Youell and for attempting to escape by sawing the bars in his cell in September 1926. After this escape attempt, Liverman became a model prisoner. “He has thoroughly cooperated with the authorities in every way,” Youell wrote the Governor’s Office in 1932. Due to his good behavior, Liverman became a trusty in charge of the clothing shop. He was not guarded or locked in the cell building at night. Liverman wrote about his reformation in a 1929 letter to Frank Bane, commissioner of public welfare. “I was only a boy when I got into trouble,” he wrote, “and boy’s [sic] do not realize the things they do. They do not take things seriously. I am a man now and I have an altogether different outlook on life.” Governor John Garland Pollard agreed. “In view of the excellent prison record of this young man for the last seven years,” Pollard wrote on 7 June 1933, “…and upon the recommendation of the Commissioner of Public Welfare and the prosecuting attorney,” Pollard granted Liverman a conditional pardon. Liverman returned to Massachusetts where he accepted employment with his family’s bakery in New Bedford.

What became of the “Boy Bandit?” Had he truly reformed? It appears he did. In the 1940 United States Census, Donatto Siravo (i.e. Liverman) was married with a daughter and worked as a salesman. He died in 1950 in New Bedford.

Mug Shot and Prisoner Register

Benjamin Liverman Pardon File, part one

Benjamin Liverman Pardon File, part two

-Roger Christman, LVA Senior State Records Archivist