This is the third in a series of four blogs related to the “To Be Sold” exhibit which opens on October 27 at the Library of Virginia. Each post will be based on court cases found in LVA’s Local Records collection and involving human traffickers. These suits provide insight into the motivation of individuals to get into the business, as well as details on how they carried out their operations. Even more remarkably, these records document stories of enslaved individuals purchased in Virginia and taken hundreds of miles away by sea and by land to be sold in the Deep South. The following narrative comes from Lunenburg County Chancery Cause 1860-026, Christopher Wood, etc. vs. Executor of William H. Wood.

From 1834 to 1845, Richard R. Beasley and William H. Wood were business partners “engaged in the trade of negroes [sic], buying them here [Virginia] & carrying them to the South for sale.” It was a partnership that was renewed every twelve months. Over the next decade, other individuals such as Robert R. Jones invested in the partnership but Wood and Beasley were the primary participants. The enterprise was funded by the personal capital of the partners, as well as loans from banks and private individuals. For example, in 1838, Beasley invested $5,800 and Wood $2,343 and they borrowed $6,905 from the Bank of Virginia and private individuals for a combined total of $15,048. In 1844, the total investment by the partners was $27,213 with over $24,000 invested by Beasley alone.

The partnership generally operated in the following manner: Beasley purchased the enslaved individuals in Virginia and Wood managed the transportation and selling of the individuals in the towns of Natchez and Port Gibson, Mississippi, and in New Orleans, Louisiana. The business proved to be very successful, bringing in large profits to the partnership. In 1836, Beasley and Wood purchased in Virginia 19 enslaved males, 12 enslaved females, and one child at a total price of $27,601 and sold them in Port Gibson, Mississippi, for $43,626. Expenses for transportation, clothing, food, etc., were $1,955, leaving a net profit of $14,070 to be divided among the partners. In 2014 dollars, that would be almost $303,000. (I used the Federal Reserve Bank Consumer Price Index (Estimate) calculator for this figure) The partnership experienced great losses following the Panic of 1837. However, beginning in 1840, they were once again enjoying huge profits until Wood’s 1845 death, which ended the partnership. William H. Wood died in Gainesville, Alabama, while transporting enslaved individuals to sell in Mississippi.

Following Wood’s death, Beasley became the administrator of his estate. As such, he was responsible for settling all of Wood’s debts, which were substantial. He was forced to sell enslaved individuals, land, and crops to satisfy Wood’s creditors. Consequently, very little of Wood’s estate remained to be inherited by his heirs. They were not happy with the small amount left to them and sued Beasley for mismanagement of the accounts. They accused him of not disclosing profits from the partnership that rightly belonged to Wood, as well as illegally using funds from Wood’s personal estate to pay debts owed by the partnership. Wood’s heirs sued, asking the chancery court of Lunenburg County to review the partnership’s accounts in order to determine a fair settlement.

Both sides filed depositions and exhibits including correspondence, receipts, and contracts that offer an inside look into the business of trafficking enslaved people. In a letter to William H. Wood dated 24 January 1845, Beasley praised him for the profit received from a recent sale of enslaved individuals. Aside from the sale of one family which he thought was “too cheap,” he was “perfectly satisfied.” He went on to write about the “brisk” market in Virginia noting that 450 to 550 enslaved girls were selling for $350 to $450 each. He also gave his thoughts on the immediate future of the human trafficking market and the impact cotton and tobacco prices would have on prices that enslaved individuals were sold for.

“I don’t think the market can be glutted with cheap negroes [sic]. Though I am still of the opinion that negroes must fall though the last accounts of cotton it was firm & rising. If that continues the next new negroes will be brisk and probably will rise in the New Orleans market. They [Negroes] may be scarce here in consequence of tobacco’s rising. It’s selling from 8 to 11 dollars. That may have a tendency to make negroes a little scarce for a while. I think the trade will be great next year. I want you to go for every dollar.”

Beasley offered Wood some advice on when was the best time to get “every dollar.” He advised that Wood should strike quickly, as soon as the local planters brought their cotton and wheat to New Orleans to put on the market, and to sell the enslaved individuals for cash only. He was not to wait too long because the planters were “more apt to disappoint you after they have sold their cotton and wheat” and would want to purchase on credit. Beasley warned Wood: “Even you don’t go for credit.” This warning was given for good reason. A deponent in the chancery suit recalled a conversation with Wood in 1844 asking for his advice on getting into the business. Wood advised him not to “as there was nothing to be made at it.” Wood informed the deponent that he was owed somewhere between $10,000 and $12,000 for enslaved individuals sold to Southern planters on credit (approximately $279,000 in today’s dollars).

As Beasley pointed out in his 24 January 1845 letter to Wood, the price of forced labor was dependent on the price of cotton. In a letter to Beasley dated 15 December 1844, Wood wrote from Gainesville, Alabama, that he recently sold “Martha & her children [at a] price $1,000 less than they ought to have sold.” This was also the case with the other enslaved individuals he sold. The reason? The falling price of cotton. He told Beasley, “to think of negroes maintaining the former prices when cotton was worth eight cents is the heighth [sic] of folly I think.” Beasley pressured Wood to send him money made from a recent sale. Wood agreed to do so but pleaded with Beasley not to use the money to purchase more enslaved individuals in Virginia. “(T)hey must come down from one hundred to two hundred dollars … four hundred is as much as ought to be paid for [enslaved] men.”

Lunenburg County Chancery Causes, 1860-026, Christopher Wood, etc. v. Executor of William H. Wood

The documents filed in the chancery cause also bear witness to the experiences of the individuals who were sold by Beasley and Wood. A deponent named George C. Hatchett was asked about the sale of a woman owned by William H. Wood. Hatchett stated, “He kept the negro [sic] woman 8 or 10 months, when he told me, that he should carry her South, because two negro men were claiming her as a wife, and he [Wood] feared she might cause some disturbance.” Next week’s blog will endeavor to tell the stories of some of the enslaved men and women bought and sold by Beasley and Wood.

Christopher Wood, etc. vs. Executor of William H. Wood, 1860-026, is part of the Lunenburg County Chancery Causes, which are available for research at the Library of Virginia. The processing of this collection was made possible through the LVA’s innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP) which seeks to preserve the historic records of Virginia’s circuit courts.

Next week: Hester Jane Carr’s Story

Header Image Citation

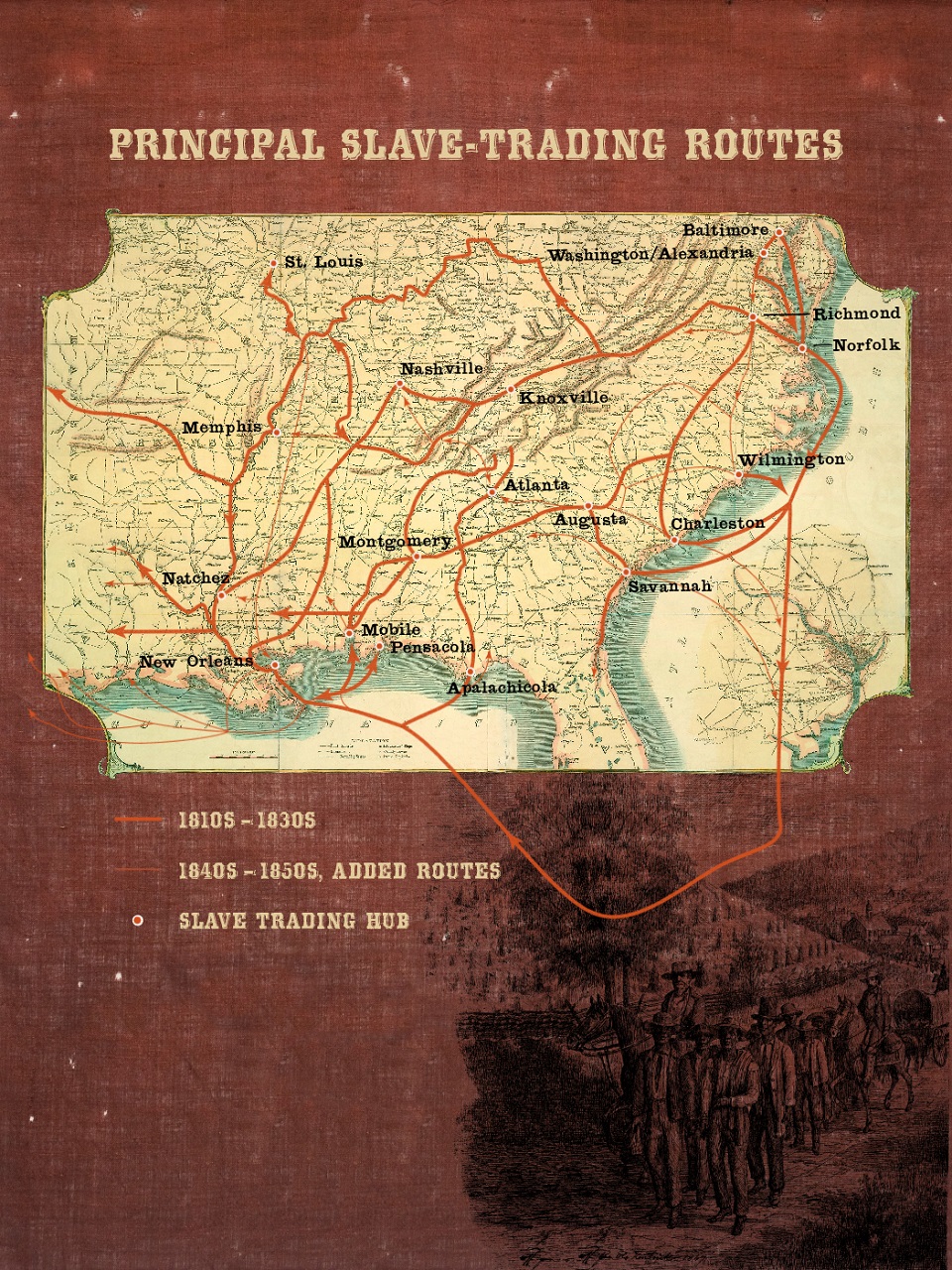

Principal Slave Trading Routes, 1810-1850 ca. Provide in part by Calvin Schermerhorn and the University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab.

If Beasley and Wood in 1836 paid $27,601 for slaves in Virginia and sold them for $43,626, with expenses of $1,995, their net profit was $15,070 — not $41,670 as stated in the article. Using the same Federal Reserve Bank Consumer Price Index used in the article to calculate today’s worth, their profit would be $324,188 in 2014 dollars.

Mr. Paterson,

Thank you for the corrections. As history majors, math is not necessarily our strong suit. 😉 We appreciate the double-check and have made the corrections.

Hi,

I am researching my dad’s family. I think I found my great great grandfather Tom Dodson on Ancestry on a slave manifests from 1807-1869. It shows he arrived in New Orleans Dec. 22, 1838 on the Isaac Franklin, The co-signee of the property was Richard R. Beasley. The port of departure was Norfolk, VA. I found Beasley on your website showing Beasley was in slave buying business with William Wood. If this is my great great grandfather he ended up in Fayette County, Texas.

If you can give me direction on how to research where he ended up and/or how and when he was bought it would help me

Debra Pendleton

Ms. Pendleton,

I consulted a colleague who offers the following advice:

“Historic New Orleans has online site called Lost Friends – http://www.hnoc.org/database/lost-friends/search.php – containing ads written by former slaves looking for family members.

As far as finding when and how he was bought, that’s tougher. Slave traders typically purchased slaves at auctions. They were private transactions that would not necessarily be recorded in a local court unless there was a law suit between the parties.”

You might also consult a professional genealogist with extensive experience researching African Americans in the pre-Civil War era.

Best of luck in your research.

Its a shame the Lunenburg County court records aren’t digitalized yet on the Library of Virginia Chancery record site.

The Lunenburg Co. chancery causes are available on microfilm through inter-library loan (ILL) at no charge (from the Library of Virginia). You may request the desired reels through the ILL desk of your local library.

Not sure the Beasley in this blog is related to the Beasley I’m looking for, but…I am researching my gg grandparents Green or Greenhill Jones and Elmyra or Myra Jones (Prince Edward County, VA). Both may have been owned by a D. A Beasley (according to the Prince Edward County Register of Cohabitation records, 1866). How can I find info on D.A. Beasley (or Beazley)?

Thank you for your inquiry. If you are within driving distance of the Library of Virginia, we suggest visiting our research rooms. Our collections contain numerous published and manuscript sources on Prince Edward County that may be useful to your research. To get a sense of the variety of materials that we hold, you may wish to search the online catalog at https://bit.ly/2s4PlJt. If you are not within driving distance, some printed and microfilm materials can be requested via inter-library loan through your local public library.

After searching the catalog, if you have questions about resources that you find, please contact the Archives Research Services staff at 804-692-3888 or archdesk@lva.virginia.gov.

Thanks for reading Out of the Box!