In November of 1852, William Makepeace Thackeray, still enjoying the considerable success and fame accruing from his novel of the previous decade, Vanity Fair, arrived after a two week voyage from Liverpool (on the Royal Mail ship “Canada”) in Boston harbor. Thackeray’s purpose, besides adventure, was financial gain, a cushion for his daughters from a life he suspected might be foreshortened. In fact, it was–He died ten years later at only 52.

The lecture route, somewhat planned and somewhat improvised, would take a leisurely southern direction, with an appearance in Richmond scheduled for the following February. Thackeray was accompanied by Erye Crowe, who acted as personal secretary, tour manager, amanuensis and, most importantly, good company during what promised to be a stimulating, but inescapably trying and lengthy journey.

The lecture route, somewhat planned and somewhat improvised, would take a leisurely southern direction, with an appearance in Richmond scheduled for the following February. Thackeray was accompanied by Erye Crowe, who acted as personal secretary, tour manager, amanuensis and, most importantly, good company during what promised to be a stimulating, but inescapably trying and lengthy journey.

Like Thackeray, Crowe was a skilled sketch artist. Unlike Thackeray, who abandoned art studies as a young man to sketch words as a journalist, Crowe, 29 years of age and about a dozen years the author’s junior, still aspired to be an artist. While Thackeray’s lectures and impressions of America inscribed in his letters now interest only scholars, Crowe’s oil painting, “Slaves Waiting for Auction”, derived from his drawing above, can still jab the conscience.

The work acts as centerpiece for the Library of Virginia’s exhibit opening later this month, “To Be Sold,” a close examination of Richmond as a distribution hub for the business of selling human beings.

Yet minus the intercession of a book and a newspaper, the painting might not exist at all. “I expended 25 cents”, writes Crowe in his memoir of 1893, With Thackeray in America, “in the purchase of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and was properly harrowed by the tale told by Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe.” He was joining a readership of some 300,000-the estimated copies sold the previous twelve months since publication. “But Thackeray declined to plunge into its tale of woe,” Crowe wrote, “judicious friends had dinned well into his ears the propriety of his not committing himself to either side of the Slavery Question, then a burning one, if he wished his career as a lecturer not become a burthen to him.”

So upon arrival in Richmond……while Thackeray was preoccupied with the social obligations that rapidly collect about such a well-known personage, Crowe, decided to explore.

“The 3rd of March, 1853, is a date well imprinted on my memory,” he wrote in With Thackeray in America, “I was sitting at. . .breakfast by myself, reading the ably conducted local newspaper, of which our kind friend was the editor. It was not, however, the leaders or politics which attracted my eye, so much as the advertisement columns containing the announcements of slave sales, some of which were to take place that morning in Wall Street, close at hand, at eleven o’clock.”

Our archival holding of this decade includes the four major papers serving Richmond at the time but, regrettably, a few missing issues prevent us from claiming with complete confidence that this indeed was the ad delivered to Crowe’s curiosity. Just the same, let’s say, if not certain, we’re reasonably sure.

The artist in Crowe realized the visual possibilities of the slave auction setting, “Ideas of a possibly dramatic subject for pictorial illustration flitted across my mind; so, with small notepaper and pencil, I went thither, inquiring my way to the auction rooms.” He didn’t have far to go–The commercial area where slaves were bought and sold, then called Wall Street, was within easy walking distance of the American Hotel (click to enlarge map).

Crowe visited more than one auction house and at his last stop, sketched what he saw inside. “I got to the largest end store,” he wrote, “I thought it might be possible to sketch some of the picturesque figures awaiting their turn. I did so. On rough benches were sitting, huddled close together, neatly dressed in grey, young negro girls with white collars fastened by scarlet bows, and in white aprons. The form of a woman clasping her infant, ever touching, seemed more so here.”

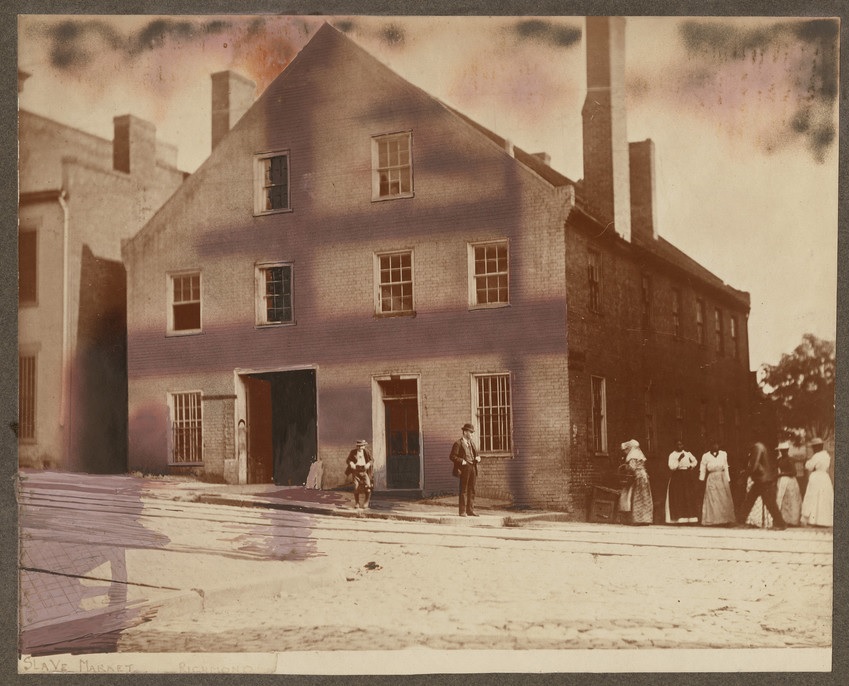

Site once used as a slave auction house in Richmond, Virginia shortly before its destruction.

A New Yorker, who had witnessed the scene explained that Crowe, “began to take a sketch, and had proceeded quite far before he was noticed by anyone but myself. At last he attracted some of the attention of the bystanders, until full twenty or more were looking over his shoulder. They all seemed pleased with what he was doing, so long as the sketch was a mere outline, but as he began to finish up the picture, and form his groups of figures, they began to see what he was about.” What some likely suspected Crowe was “about” was a political act in sympathy with northern abolitionists. To Crowe’s considerable relief, he departed unscathed and the incident was unaddressed by the local press and forgotten.

“Crowe has just come from what might have been and may be yet a dreadful scrape,” Thackeray wrote in a letter to friends posted from Richmond, “He went into a slave market and began sketching; and the people rushed on him savagely and obliged him to quit.”

Thackeray was relieved that the incident didn’t attract undo attention so his lectures (looking back to the politically distant 1700s) at the Athenaeum could continue without distraction.

The Library of Virginia’s exhibit “To Be Sold” opens to the public Monday, October 27.

p.s. While assembling our own map, we discovered an interactive map of Richmond’s slave market done by the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond.