This is the first in a series of four blog posts concerning post-Civil War Virginia and the lives of freedpeople after Emancipation. The posts precede the Library of Virginia exhibition Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation opening 6 July 2015.

Black assertions of personal, political, and economic autonomy and freedom after the Civil War ran headlong into white resistance. Southern whites, embittered by the war and desperately clinging to an antebellum model of race relations, violently attempted to enforce labor contracts, social mores, and claims to political supremacy. Local and state records, newspapers, broadsides, engravings, and federal records on microfilm in the Library of Virginia’s vast collection reinforce the frequency and brutality of violence in this turbulent period.

Before the Civil War, Virginia whites of all classes exerted repressive control over enslaved people through legal codes, harsh punishments, slave patrols, pass systems, and the threat of sale. Whites were especially fearful of slave rebellions. Emancipation and the occupying Federal army took away that control, and white fears of retribution became palpable.

Whites openly talked of an impending “Race War,” and attempted to disarm African Americans and re-arm whites. In Louisa and Culpeper Counties, the confiscation of arms from African Americans prompted officials of the Freedmen’s Bureau to order the weapons returned. Adjutant General William H. Richardson wrote to Governor Frances Pierpont in support of an Elizabeth City County petition to send arms to white residents.

“On the last anniversary of American Independence a body of Negroes mounted and armed with United States Sabres [sic] and pistols, paraded through the streets of the City of Richmond, and I am credibly informed that a system of nightly drill is kept up by them at more than one place in the City. Who can foresee what may be the end of this state of things? If there are any who desire the massacre of the whites by the blacks, that may, and probably will occur to a partial extent as one result, but if it does, the utter annihilation of the Negroes will as certainly follow it, as the night succeeds the day.”

Richardson’s prediction of violence would certainly come true, but not because of African American aggression. Whites reacted violently to even the simplest assertions of basic rights. In 1866, African American residents of Norfolk celebrated the passage of a national Civil Rights Act. One of the earliest Black newspapers, the True Southerner (available at the Library on microfilm) reported that “threats had been made in different parts of the city by white citizens that the colored people should have no celebration on this occasion.” The parade proceeded with marchers carrying banners including one that proclaimed “The Ballot Box Free to All.” The procession was pelted by rocks and bricks and soon the accidental discharge of a weapon caused a fracas between marchers and a city police officer that resulted in several casualties. Major F. W. Stanhope of the garrisoned 12th Infantry Regiment anticipated possible violence and quickly quelled the affray but violence continued through the night as armed bands of whites attacked blacks—at least two were killed and others seriously injured. The regiment came under fire from well-organized units of former Confederates “dressed in rebel gray.” Stanhope asked his superiors to declare martial law due to the inability—or unwillingness—of city officials to control “these people and their prominent hostility to the rights and privileges of the Colored Population.”

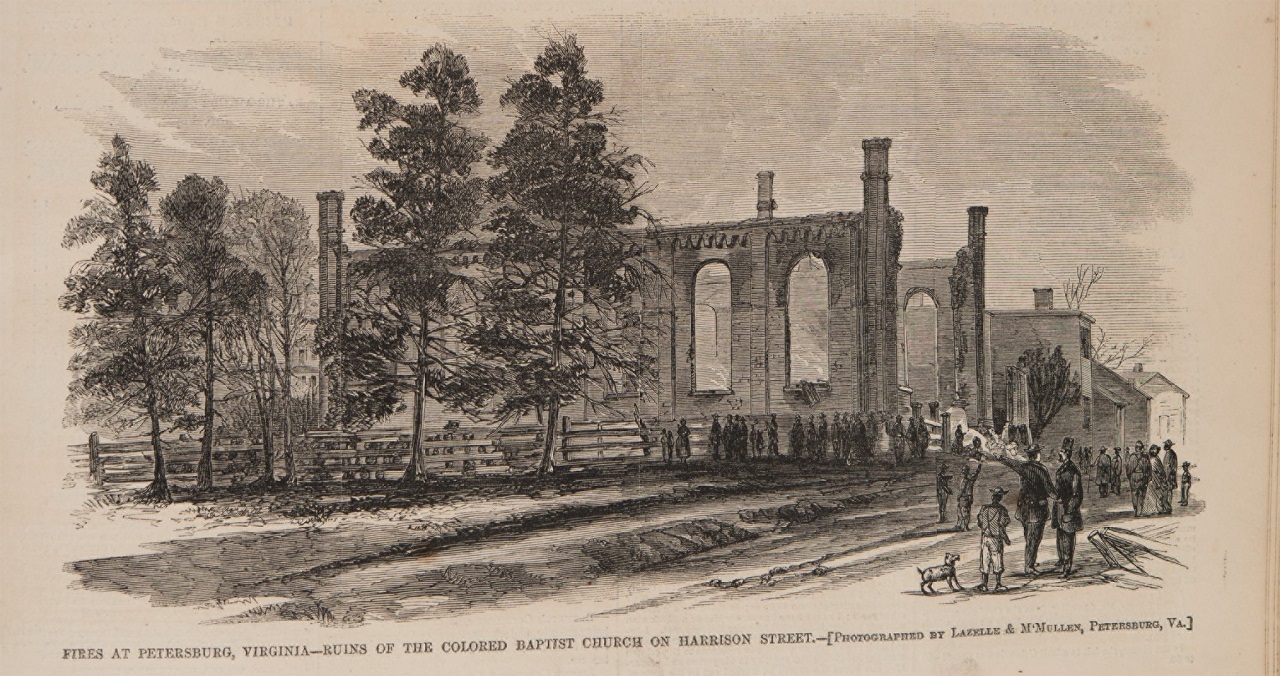

Many whites violently resisted African American attempts at educational advancement through the many Freedmen’s schools run by African Americans and northern philanthropic and religious societies. The Freedmen’s Bureau records for Virginia, available on microfilm at the Library, document numerous cases of school arsons in the first few years of Reconstruction in Virginia, and many more attacks on schools, teachers, and churches. Harper’s Weekly reported on a night of destruction in Petersburg, where “there is yet enough left of the old barbarism of slavery to incite to the wanton destruction of churches for no other reason than that they are frequented by colored people.” Arsonists burned the Sunday school of the Union Methodist Church and the newly constructed African Baptist Church to the ground. Additionally, “during the progress of these fires attempts were made to burn two other African churches, the old African on Harrison Street, now used as a school-room, and the Gillfield, quite a handsome edifice on Gill Street.”

Most violence between blacks and whites occurred between individuals over matters such as a labor contract, a breaking of racial etiquette, or a political argument. While these might remain small confrontations, they also had the potential to spiral out of control. Even after the end of Reconstruction in 1870, tensions in Virginia remained high as African Americans continued to push for their political, educational, and social rights. The so-called Danville Circular denounced “Coalition Rule in Danville” and was published as a supplement to the Staunton Vindicator in 1883. By the 1880s Danville was a burgeoning industrial center with a majority African American population. The city was a bastion of the Readjuster Party, the black-white political coalition that had controlled Virginia since 1879. The Circular complained about African American control of public offices and the city market, and that African Americans did not show due deference to whites in public:

“They infest the streets and sidewalks in squads, hover about public houses, and sleep on the doorsteps of storehouses and the benches of the market place. They impede the travel of ladies and gentlemen, very frequently forcing them from the sidewalk into the street. Negro women have been known to force ladies from the pavement, and remind them that they will ‘learn to step aside next time.’ “

On 3 November 1883, a young white clerk approached two Black men on the sidewalk of Danville’s Main Street. The clerk tripped over the foot of one of the men and words were exchanged. The clerk attacked one of the men and ended up knocked down into the gutter. Such was the seemingly minor incident that led to a full scale race riot. The clerk returned with armed white men and another fight broke out, attracting the attention of black and white policemen and a large crowd of Africans Americans in town for market. As tensions rose, shots rang out from the armed whites; estimates are that 75 to 200 shots were fired in the space of two or three minutes and at least four blacks and one white died. Armed whites took over the streets over the next few days and routed the Readjusters at the polls the following Tuesday.

Unfortunately, the documentary record of the post-emancipation era in Virginia belies the oft-asserted claim that emancipation in Virginia was somehow less troubled and violent than in Deep South states. The records at the Library of Virginia also point to the continued and intense white resistance that would lead to the ultimate triumph of the Conservatives and the stripping of Black political rights through the 1902 Constitution. It would take the “Second Reconstruction” of the 1950s to restore some of those lost rights.

Check back at Out of the Box next week for a post on education in post-Emancipation Virginia.

Issues of the True Southerner published in Hampton, Virginia are now available on Virginia Chronicle here.

–Gregg Kimball, Public Services & Outreach Director