This is the second in a series of four blog posts concerning post-Civil War Virginia and the lives of freedpeople after Emancipation. The posts precede the Library of Virginia exhibition Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation opening 6 July 2015.

“It is too plain that this people still love Slavery with some blind Madness.” Jacob Eschbach Yoder (February 22, 1838–April 15, 1905), a transplant to Virginia from Millersville, Pennsylvania, had lived in Lynchburg for only a month when he noted this observation in his diary on April 28, 1866. The Civil War had ended the Confederacy’s dream of a slaveholding nation, but Yoder perceptively feared that white Southerners had “only accepted the result of this war, because they must.” A teacher who had come to Virginia after the Civil War to help educate the freedpeople, Yoder perceived that many whites “hate every measure that is intended to elevate them. Education is their only passport to distinction. Therefore the whites so bitterly oppose it.”

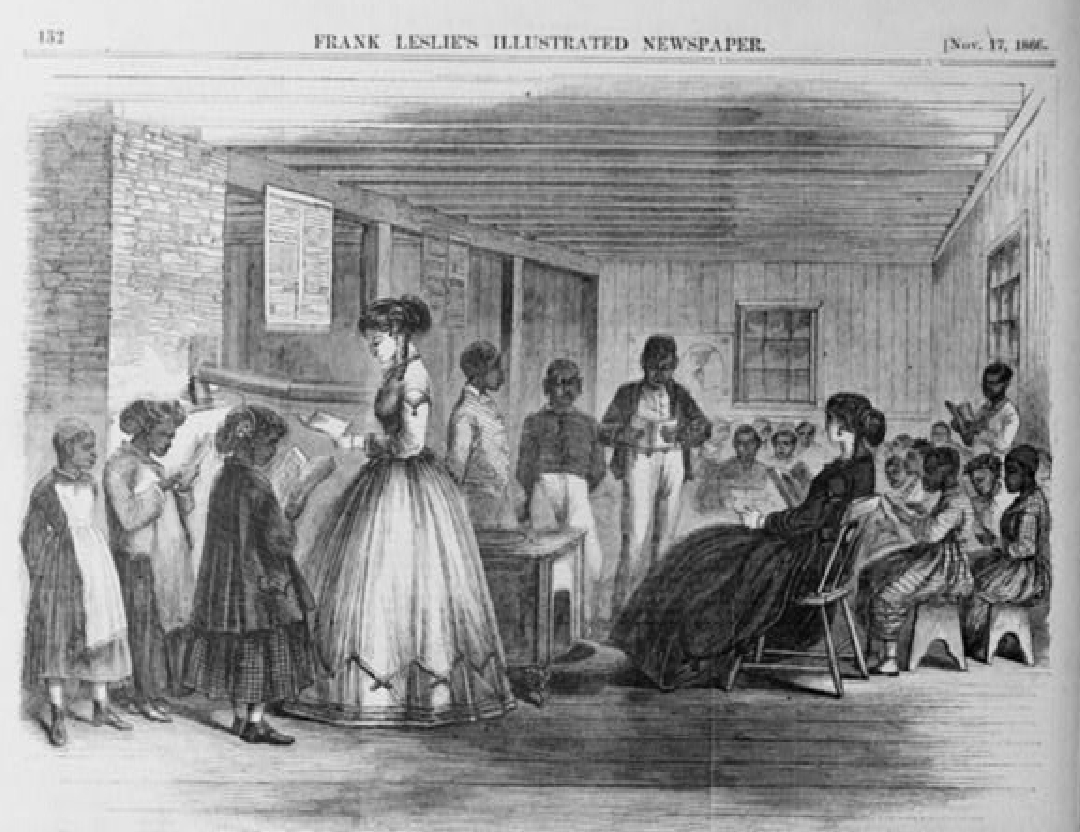

Shortly after the Civil War began, African Americans of all ages, both free and enslaved, quickly took advantage of any chance to gain the education that had been denied to them under slavery. Despite widespread and often violent opposition from white Virginians, opportunity came from a variety of sources.

During the war, numerous religious and private organizations began sending people to Virginia to teach in schools established for and by the freedpeople. After the war, the Freedmen’s Bureau provided the infrastructure to create, maintain, and administer schools across Virginia and the South, although it relied on funding, supplies, textbooks, and teachers provided by Northern missionary and aid societies, including the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association (PFRA). Jacob Yoder was one of those teachers. Influenced by his religious convictions, Yoder joined a stream of white Northern educators and missionaries who headed south in the first days of Reconstruction, bent on lending a collective hand to the newly freed population.

Yoder served initially as principal of the Camp Davis School, Lynchburg’s first educational institution for its African American population. His first stint in Lynchburg lasted only a few months, and in June 1866 Yoder returned to Pennsylvania, where he tried to establish his own private school. Yoder came back to Lynchburg in November 1868, however, as a teacher for the Freedmen’s Bureau schools, renewing a career in African American education that would last the rest of his life. Promoted to superintendent of the PFRA’s schools, Yoder oversaw more than two dozen schools in a six-county area. The schools thrived under his administration from 1868 to 1871.

In 1871, Yoder joined Virginia’s newly established and legally segregated public school system as first assistant to the principal at the African American Public School No. 7. The Lynchburg School Board promoted Yoder to supervising principal of African American schools in 1878, a position he maintained until his death in 1905 at the age of sixty-seven. In 1911, Lynchburg memorialized the white educator with the naming of the Yoder School, a black school within the city’s segregated system.

Despite his idealistic intentions and notable successes, Yoder’s diary (kept from 1866 to 1870) records a deep ambivalence about his job, the abilities of his colleagues, and the prospect of African American education. He considered education vital to the economic development of the African American community. Yet he sometimes expressed his doubts that “our schools have done but little good to the Colored People” (December 11, 1868). The volumes of Yoder’s diary are in the Personal Papers Collection at the Library of Virginia (Accession 27680). The diaries for 1866–1867 and 1869–1870 have been published as The Fire of Liberty in Their Hearts: The Diary of Jacob E. Yoder of the Freedmen’s Bureau School, Lynchburg, Virginia, 1866–1870 (Library of Virginia, 1996). In 2014, the Library of Virginia acquired Yoder’s diary for 1867–1868, which is available for viewing in the Manuscripts Reading Room, as is Yoder’s letterbook covering the period of March–December 1870 (Accession 35108).

Jacob Yoder’s story is part of the Library’s exhibition Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation, which is open July 6, 2015–March 26, 2016.

–Joseph M. Thompson, Exhibition Intern

Header Image Citation

“The Misses Cooke’s School room, Freedman’s Bureau, Richmond, Va.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, vol. 23, 1866 Nov 17, pg 127.