With examples dating back to the 1750s, Norfolk County chancery causes offer an interesting set of solutions to some of the myriad problems associated with a growing county, especially in the form of injunctions. These were legal remedies filed by plaintiffs hoping to stop or halt a particular action. The resulting court order would enjoin and restrain the defendant from committing the action. During this process, the plaintiff filing the injunction was required to post a bond, although monetary relief was not usually the end result. Instead, injunctions helped to preserve the status quo in the community and prevent possible injustice. Failure to comply with an injunction resulted in punishment for contempt of court.

The chancery cause Bernard (Barnard) O’ Neill v. Lewis Warrington, et. al., 1840-007, filed in Norfolk’s Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery on 27 June 1838, highlights the sometimes complex issues involved in an injunction. Barnard O’ Neill alleged title to 55 ½ acres of land around the town of Portsmouth. His bill of complaint states that he received a patent for this land from the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1826. An adjoining property owner sold 60 acres of his property to the U.S. Government in 1828. According to Richmond C. Holcomb, M.D., writing in 1930, the western boundary between O’Neill’s property and this government property had been in dispute since 1832. Holcomb’s book, A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital, can be found in the Library of Virginia’s collections.

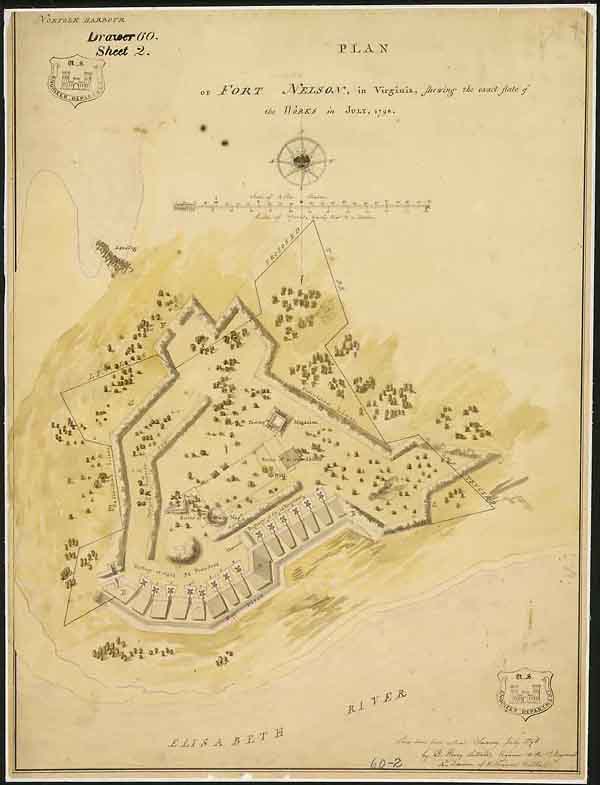

The adjoining property owner, Thomas Newton, Jr., originally allotted 18 acres to the government in 1799 for the rebuilding of Fort Nelson. He then conveyed 60 acres to the government for a naval hospital. Founded in 1827, Portsmouth Naval Hospital is the nation’s oldest naval hospital. Materials salvaged from Fort Nelson’s demolition were used in its construction. O’Neill contended that Newton distributed more acreage to the government than was conveyed to his father, Thomas Newton, Sr., by the executors of Robert Tucker in 1794. In a letter addressed to the Commissioner of Hospitals on 17 March 1832, O’Neill wrote that, “he is unwilling to bring suit against the government, though they have committed a serious trespass by burying their dead on land I intend building on or selling.” He went on to say that, “many persons wish to purchase the land and my land will be an advantage to the Hospital as the best place in this section of the country for fish and oysters, of which they are now deprived. As to my price, I want nothing but what is perfectly fair.” Eventually, he named his price—five thousand dollars.

O’Neill wrote to his state representative from Norfolk County, John W. Murdaugh, on 19 December 1832, explaining the boundary dispute and supplying depositions. These letters, part of Accession 36912, are found in the Library of Virginia’s State Records collection. In turn, Murdaugh supported O’ Neill’s claim and wrote to the Secretary of the Navy. When the dispute continued, O’ Neill decided to file an injunction in Norfolk County. In his injunction, O’Neill explains that the U.S. Naval officers in charge of the land were burying dead bodies from the hospital on his property (the site of the hospital’s first graveyard), cutting down trees , and erecting an enclosure around these lands. The chancery cause was eventually dismissed on 9 June 1840 due to the plaintiff no longer appealing.

Bill, Norfolk County, Chancery Causes, 1840-007, Bernard (Barnard) O’Neill v. Lewis Warrington, et al., Local Government Records, Library of Virginia.

The dispute, however, did not end there. In early 1840, with the help of Murdaugh, the matter was referred to the United States attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, R.C. Nicholas. Nicholas then wrote a letter to the Solicitor of the Treasury, M. Birchard. Birchard, in turn, referred the letter to the Secretary of the Navy. Despite O’Neill’s best efforts, however, the United States did not deem his claims just. The U.S. government erected a fence along the western boundary. Further correspondence regarding the case was lost during the Civil War. All questions regarding the boundary, however, were settled by 1852. Barnard O’Neill went on to become an extensive land owner in Portsmouth.

Portsmouth Naval Hospital

Courtesy of dhr.virginia.gov

Other injunctions filed in Norfolk County from 1840-1882 were related to the unauthorized cutting of timber, transporting slaves beyond the limits of the commonwealth, property ownership, money paid over by business and government entities, the regulating of ditches, the manufacture of bricks, and the laying of a telegraph cable. These appear in stark contrast to today’s injunctions, which largely involve stalking, harassment, domestic violence, copyright infringement, and the unauthorized practice of law, to name a few.

Bernard (Barnard) O’Neill v. Lewis Warrington, et. al., 1840-007, is part of the Norfolk County Chancery Causes, which are currently closed for digital reformatting. Images will be posted to the Chancery Records Index as they become available.

The processing and scanning of the Norfolk County chancery causes were made possible through the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts.

Thanks for sharing that Callie, interesting story. I didn’t know about the hospital or Fort Nelson.

Hello,

I’m looking for further information about Barnard O’Neill and his family.

If someone could give me, that would be wonderful.

Thanking you in advance.

Louis de La Rochefoucauld

lagestiondirecte@gmail.com

(from France)

I am somewhat mystified by the practice of posting images of maps that are so low-res that even the larger image has compression artifacts, and a good portion of the wording on the map is unreadable. It would be nice indeed if you folks could up the resolution enough for the map to be read. Thank you.

(Currently researching Skirvin, Skirven families in Colonial Virginia and Maryland, including Vestryman/Justice George Skirvin, his son John, his grandson George, his brother Frances Skirvin; slave owner/merchant, and the third brother, William Skirvin, a physician. the location of the Ordinary owned by Frances Skirvin, location of property known as “Skirvin’s Neglect”, etc. Thank you!)

Ms. Johnson,

Assuming that you are referring to the “Plan of Fort Nelson” by B. H. Latrobe (1798) in this post, we have provided the highest quality image available from the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) online exhibition “Designs for Democracy.” http://1.usa.gov/1MWTXXc Citations for images are provided so that readers can further research images and documents. For the fort plan, no high quality online surrogate appears to be available.

Images from Out of the Box are not necessarily meant to replace online or original sources, but rather to provide some literal illustration of some aspect of the text. Because of image size limitations in WordPress, we cite the original documents (whether digitized or analog) so that more detailed copies can be researched by our readers, if they are so inclined. The images provided in the Library’s online databases are much higher quality and that is where more detailed research should be conducted. In this instance, because the materials cited are in another institution’s collections, the quality of the reproduction is out of our hands.

I hope this clarifies the intent of illustrations provided in Out of the Box. We do appreciate your readership and hope that you continue to find the content engaging and interesting. Thank you for your question.