Editor’s note: This blog post marks the close of the grant-funded Montgomery County chancery processing project (in Civil War terms, the “Last Dispatch”). Thanks to generous support by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), over 200 boxes of Montgomery County chancery are now flat-filed, indexed, conserved, and awaiting digitization. Dedicated LVA staff Sarah Nerney, Regan Shelton, and Scott Gardner, along with assistance from Clerk of the Circuit Court Erica W. Williams and her staff, completed not only the processing of chancery records but the organization and identification of scores of other historical court records. To revisit some of the discoveries made over the course of this two-year project, re-read some of the earlier blog posts. The chancery causes are now slated for digital reformatting. Researchers should contact the Montgomery County Circuit Court Clerk’s office with inquiries regarding access or copies.

When one thinks about the Civil War, usually the first thoughts are about military battles, but there were many battles fought in the courts over resources such as supplies and land. The chancery records in Virginia’s courthouses can provide tantalizing insights into conflicts on the home front. They also reveal how complicated life became in Civil War Virginia as individuals, businesses, and even localities fought each other and the Confederate government to defend their property or what they viewed as rightfully their property. Such cases shed an intriguing light on the war effort and provide a fuller picture of the conflict. Three such cases occurred in Montgomery County: 1864-004, Orange and Alexandria Railroad Co] vs. Roberts S. Newlie, etc.; 1864-005, James P. Hammet vs. General John C. Beckinridge; and 1864-009, Lewis F. J. Amiss, etc. vs. Major Thomas L. Brown, etc. All of these offer glimpses into this complicated world and also show that valuable information about the Civil War can be hidden in unexpected places.

In the first case, 1864-004, Orange and Alexandria Railroad Co] vs. Robert S. Newlie, etc., the Orange and Alexandria Railroad brought suit over the impressment of supplies during the war, namely wheat. The railroad’s argument was that it had a contract to move resources for the Confederate war effort, be they troops or materials, and they needed the wheat to feed their staff. The wheat in question had been impressed by Montgomery County, through its agent Robert S. Newlie, to feed the “indigent” wives and children of soldiers and sailors away at war. Both parties in the case had legitimate claim to the property due to the rationale for its use. Rail lines were vital for the war effort, and they certainly could not function without a well-nourished staff. Montgomery County, like every other county, faced the issue of serving the needs of a population whose traditional providers were away fighting. The decision of the court sided with the defendant, citing an Act of the General Assembly of Virginia giving localities the power to appoint agents to impress resources. The court further explained that if the actions of the agent committing the impressment of wheat were trespassing, that was not a matter to be handled in a chancery suit.

The second case, 1864-005, James P. Hammet vs. General John C. Breckinridge, is principally an injunction against the use of private land as the location of supply buildings and a boat launch for the Confederate war effort. The case sheds an amazing sliver of light on the under-documented Confederate engineering department, especially on Major Richard L. Poor, who was then the chief engineer of the Department of Western Virginia. The complainant was James P. Hammet, a medical doctor who served as a surgeon during the war. He opposed the proposed construction on his property, stating that it would block his only access to a mill and that the presence of troops and their ensuing privations would destroy the value of his property. He argued that the construction could take place at the nearby rail bridge crossing the New River, where there had previously been a structure.

Answer of Montgomery County via Agent Robert S. Newlie, Montgomery County, Chancery Causes, 1864-004, Orange and Alexandria Railroad Co. vs. Robert S. Newlie, etc., Montgomery County Circuit Court, Christiansburg, Virginia.

The defendant, General Breckinridge, countered Hammet’s argument by relying on information from his engineer, Major Poor. Poor and Breckenridge wanted to use proposed site because it had easy access to the river, and the closer proximity to their final destination would save at least a day in transporting supplies. This speaks to the little-known fact that although it has traditionally been viewed as a non-navigable river, the New River was being used as a shipping lane. During the Civil War it was used to send supplies from the Central Depot in Radford to “Narrows on the New,” which was a gateway into the hotly contested territory of West Virginia. General Breckinridge mentioned in his answer that shipping on the New River was a tremendous advantage over carrying the same products over difficult terrain, saving time and resources. Despite these arguments, the result of the case was an injunction against the construction of the supply building and boat launch.

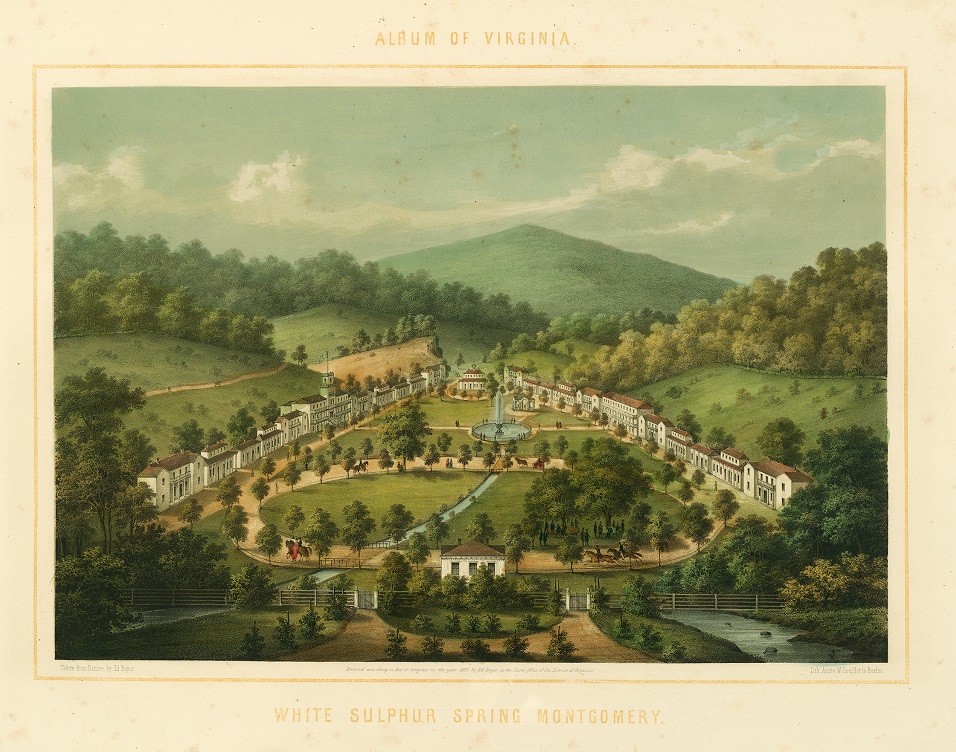

In the final case, 1864-009, Lewis F. J. Amiss, etc. vs. Major Thomas L. Brown, etc., the issues of land and impressment both came into play. Lewis F. J. Amiss and John N. Lyle were renting the Montgomery White Sulphur Springs farm on which they had a garden of about four acres immediately adjacent to John Lyle’s residence. The farm was part of a resort whose hotel had been converted to use as a Confederate hospital. The quartermaster, Major Thomas L. Brown, sought to use the garden in question to supply food for the hospital’s patients. The complainants both opposed this as the garden was their means of providing for their own families. Amiss and Lyle claimed they would not be able to find a comparable garden for themselves under half a mile away, and they also feared the presence of troops would bring damage to improvements they had made on the garden property. They further stated that there were other lands closer to the hospital site that would be better for the hospital’s purposes. An injunction was granted in favor of the complainants to prevent the impressment of the garden.

Montgomery White Sulphur Springs Cottage (Haley House), built ca. 1855 relocated to Christiansburg ca. 1904, now demolished

National Register Nomination Application, Virginia Department of Historic Resources

The Civil War still resonates with the public, and there continue to be new and intriguing insights into all that the war encompassed from the battlefield to the home front. These cases from the Montgomery County Chancery show that there is still much to learn about the Civil War and its effect on the nation and the population.