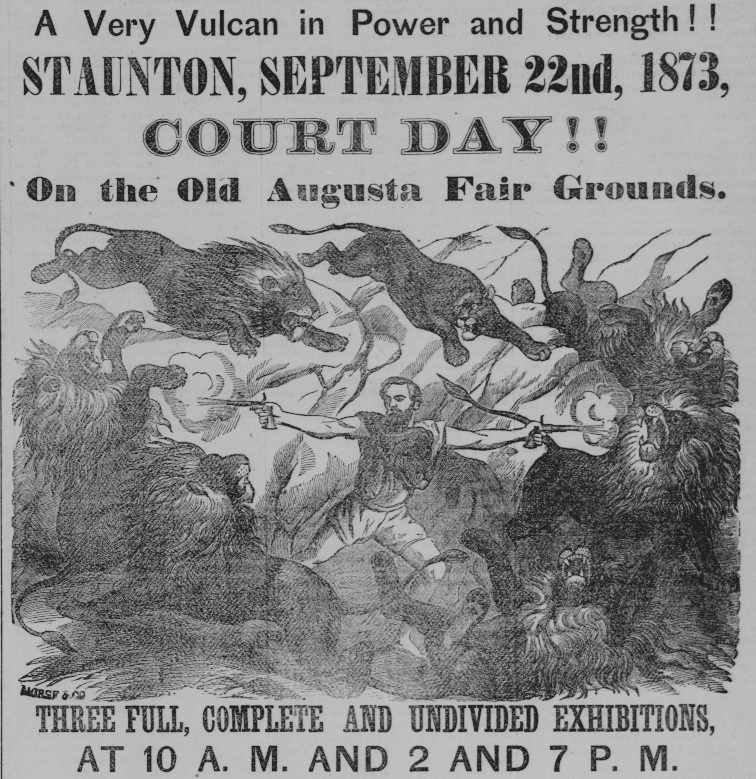

It’s September 16, 1873 in the sleepy town of Staunton, Virginia. You can only imagine a reader’s excitement at turning to page three of the Staunton Spectator to discover an ad for Lewis Lent’s New York Circus with its illustrations and long list of spectacular attractions: For a mere seventy-five cent admission (fifty cents for children under ten), one could see grand balloon ascension, wild beasts, breathing sea monsters, ornately plumed birds, flesh eating reptiles and 5000 museum marvels!

Born in upstate New York in 1813, Lewis Lent began his circus career in 1834. Soon after, he became a partner in the Brown & Lent Circus, which moved from town to town via riverboat. Over the years, Lent joined various circus troupes, but his New York Circus, which ran from 1873 to 1874, advertised here in the Staunton Spectator, was the last show he owned and operated before retiring.

Though the heyday of the traveling circus in the US might have been a bit later, the circus advertisements in newspapers of the 1860s and 1870s are evidence of its growing popularity and allure. The impetus for such elaborate newspaper advertising was the fierce competition between traveling shows. With beautiful illustrations of zebras, elephants, hippos, giraffes and tigers, acrobats standing on horse back, uniformed musicians, dancing dogs and trapeze artists, circus advertisements were an enticing and powerful promotional tool.

In the October 12, 1877 issue of the Staunton Spectator on page three, next to want ads and announcements, there is a full two column ad for John O’Brien’s circus, “The Largest Show ever in Virginia!” The ad for O’Brien’s circus promised mechanical marvels, three full military bands, palace opera chairs, 53 dens of wild beasts and six (yes, six!) stupendous shows rolled into one.

John O‘Brien, born in 1836, became a circus owner in 1862 and eventually became a shareholder in P.T. Barnum’s Great Traveling World’s Fair. O’Brien, though, had the reputation of being a dishonest business man, with a tendency for “burning the territory,” circus jargon for committing something so offensive it meant permanent exile from a town. Who’s to say whether or not he burned the territory in Staunton, but his advertisements certainly promised tantalizing fair.

Only one week after O’Brien’s ad showed up in the Spectator, another large circus ad appeared on page three of its October 18 issue. With similar illustrations and spectacular proclamations, this week’s advertisement touted the attractions of P.T. Barnum’s “Greatest Show on Earth.” In small town Virginia, where day to day life was generally quiet and routine, it must have been a thrill to see that Miss Jennie Hengler’s Original and Electrifying Double Ménage Act and Captain Cententenus, the tattooed Greek nobleman, would soon be arriving at Staunton’s humble door.

By the time of this ad’s printing in the Staunton Spectator, Barnum was widely know for his immensely popular circus – though he hadn’t yet joined forces with James A. Bailey.

P.T. Barnum, born in 1810, had always been a master of promotion. Nearly penniless when he was thirty one, with what little capital he had he purchased Scudder’s Museum on Broadway and Ann St. in New York City. He renamed it Barnum’s American Museum and brought it back to life with changing exhibits and aggressive publicity. “The wheels started to roll in the summer of 1842,” explains the Pictorial History of the American Circus, “when Barnum acquired a hideous exhibit (a dead monkey’s head and torso sewn to a fish’s body) which he billed as the Fejee Mermaid.(53)” Barnum had bogus stories published about the oddity in newspapers supposedly written by scientists confirming the mermaid’s authenticity. The newspaper stories generated massive buzz and drew large crowds to the Museum, which meant big profits for Barnum.

The American Museum burned down in June of 1865, but Barnum leased a new building on the west side of Broadway which opened to the public on November 13, 1865. This building survived less than three years, also succumbing to a terrible fire on March 3, 1868 in which many of Barnum’s rare and valuable animals died.

He retired soon after the devastating fire, but didn’t stay retired long. In 1871, (at age 61), with the combination of rare animals, equestrians, acrobats and clowns, Barnum created the circus that would become “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

Many more advertisements like these can be found on Virginia Chronicle, the Library of Virginia’s database of digitized historical newspapers. The library also has an excellent collection of books on circus history, including The American Circus, by John Culhane,Two Hundred Years of the American Circus, by Tom Ogden and Pictorial History of the American Circus, by John and Alice Durant.

Great post, thanks!