This is the fourth in a series of blog posts on the record types found in the forthcoming Library of Virginia research database: Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative. The initial database release will be on 1 February 2016.

The Petersburg Deeds of Manumission from April 1822 relate the tale of James Dunlop and his slave, John Brown. Dunlop, suffering from an unspecified illness, traveled between Virginia’s resort towns seeking treatment. Many considered the natural springs in Hot Springs and Lexington, among others, sources of healing for numerous maladies. Dunlop decided to free or “manumit” his slave John for “John’s great and unusual attention to me while under a very severe illness.” While the pair was visiting Lexington, the local doctor was absent for some days in the country.

Dunlop experienced a spell “brought on by exposure to the rain while on a trip to the Natural Bridge, after visiting Hot Springs and using freely the hot baths.” He felt that his life “was in imminent danger.” The only person Dunlop knew in Lexington was John Brown. During Dunlop’s illness, Brown took care of him. Recalling this experience years later, Dunlop wrote:

“[without Brown’s] close and extraordinary attention in watching over my disease, administering medicines and nourishment to me, agreeable to the best of his skill night and day, it is more than probable I must have fallen a sacrifice to the complaint under which I labored; he did all he could to alleviate my distress and perhaps my life was preserved by his exertions in that instance.”

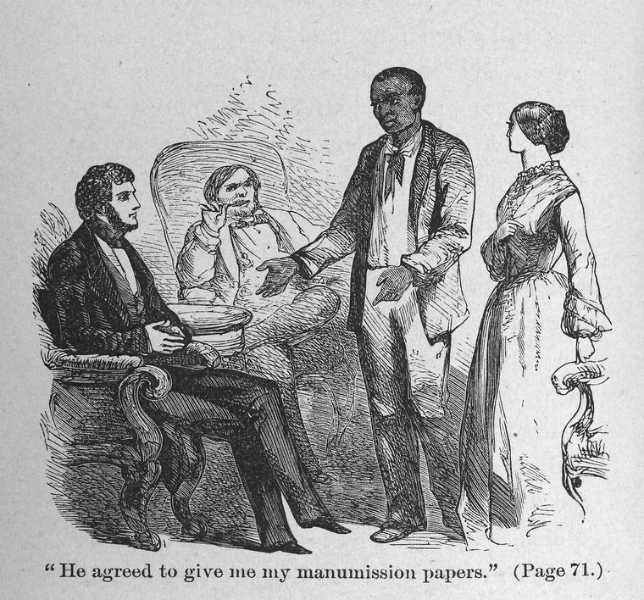

After Dunlop recovered, the two returned to Petersburg. The above narrative might have been recorded in a diary or travel journal. In fact, it is found in a local court record called a deed of manumission. Sometime after the western Virginia journey, Dunlop wrote such a deed for the purpose of freeing Brown because of “his unwearied attentions to me during my great afflictions for the last ten years” including saving his life in Lexington. He brought the deed to the Petersburg courthouse where it was recorded and filed. From that point on, John Brown was “fully and absolutely a free man.”

In 1782, Virginia passed legislation that allowed slave owners to emancipate their slaves without having to seek a special act from the General Assembly. They could do so either through a will upon their death or while alive by recording a deed of manumission. If the slave owner emancipated their slaves via a will, the executors of the deceased’s estate would provide a deed of emancipation to the court where it would be recorded and filed. A number of slave owners would include in the deed their motivation for emancipating their slaves. Some, like James Dunlop, emancipated their slaves in gratitude of their years of “faithful service.”

Others based their decision on the Enlightenment ideal that “freedom is the natural right of all Mankind.”[1] There were also those who were prompted by a spiritual motivation. In a deed of manumission freeing his deceased wife’s slave Leon Savage, Thomas Bagwell of Accomack County wrote that “God of one Blood made all nations of men and that it is his will that the black people should be free as well as the white people in society.”

One deed of manumission that was recorded and filed in Louisa County courthouse in December 1807 by Henry Jackson illuminates another motivation for emancipation. In the deed, Jackson identified himself as a former slave who “through an indulgent Providence I myself … have come to enjoy freedom.” Jackson purchased his wife Lucy and his daughter Mildred with the assistance of “several worthy gentleman” on the condition that Jackson emancipate them. Jackson agreed to do so “it being also most agreeable to my own wishes.”

Over three hundred deeds of emancipation and manumission from eighteen localities recording the freedom of over 700 enslaved men and women are currently available on Virginia Untold. More detailed information identified in the deeds of emancipation and manumission is available in a spreadsheet found here. Many records destined for Virginia Untold have been placed on the Library of Virginia’s crowd-sourced transcription project, Making History: Transcribe. If you are inspired to try your hand at deciphering early 19th century handwriting, please visit Transcribe and join our great team of transcribers.

The processing of local court records found in Virginia Untold was made possible through the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts. The scanning, indexing, and transcription of the records were funded by Dominion Resources and the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) administered by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

–Ed Jordan, Local Records Archival Assistant, and Greg Crawford, Local Records Program Manager

Test