On 23 August 1831, Governor John Floyd received a hastily written note from the Southampton County postmaster stating “that an insurrection of the slaves in that county had taken place, that several families had been massacred and that it would take a considerable military force to put them down.” Fifty-seven whites died, many of them women and children, before a massive force of militiamen and armed volunteers could converge on the region and crush the rebellion. Angry white vigilantes killed hundreds of slaves and drove free persons of color into exile in the terror that followed.

Early newspaper reports identified the Southampton insurgents as a leaderless mob of runaway slaves that rose out of the Dismal Swamp to wreak havoc on unsuspecting white families. Military leaders and others on the scene soon identified the participants as enslaved people from local plantations. Reports of as many as 450 insurgents gave way to revised estimates of perhaps 60 armed men and boys, many of them coerced into joining. The confessions of prisoners and the interrogation of eyewitnesses pointed to a small group of ringleaders: a free man of color named Billy Artis, a celebrated slave known as “Gen. Nelson,” and a slave preacher by the name of Nat Turner. Attention focused on Turner; it was his “imagined spirit of prophecy” and his extraordinary powers of persuasion that had, according to local authorities, unleashed the fury. Turner’s ability to elude capture for more than two months only enhanced his mythic stature.

While Nat Turner remained at large, rumors of a wider slave conspiracy flourished. An abolitionist writer named Samuel Warner suggested that Turner had hidden himself in the Dismal Swamp with an army of runaways at his disposal. State officials took pains to ensure that Turner lived to stand trial by offering a $500 reward for his capture and safe return to the Southampton County jail. On 30 October 1831, Turner surrendered to a local farmer who found him hiding in a cave. Local planter and lawyer Thomas R. Gray interviewed Turner in his jail cell, recorded his “Confessions,” and published them as a pamphlet shortly after Turner was tried, convicted, and executed. In tracing the “history of the motives” that led him to undertake the insurrection, Turner insisted that God had given him a sign to act, that he had shared his plans with only a few trusted followers, and that he knew nothing of any wider conspiracy extending beyond the Southampton County area.

Nat Turner’s revolt prompted a prolonged debate in the Virginia General Assembly of 1831-1832. As a result of Turner’s actions, Virginia’s legislators enacted more laws to limit the activities of African Americans, both free and enslaved. The freedom of slaves to communicate and congregate was directly attacked. No one could assemble a group of African Americans to teach reading or writing, nor could anyone be paid to teach a slave. Preaching by slaves and free blacks was forbidden. Other southern states enacted similarly restrictive laws.

Dear Sonya Coleman, Digital Collections Specialist

I am currently a Master’s student at Boston University. I am working on Turner’s Rebellion for a seminar paper that will eventually become a presentation for a conference. Is it at all possible that I could access the court proceedings of Turner’s trial?

Thank you.

-J.B.

Ms. Barringer,

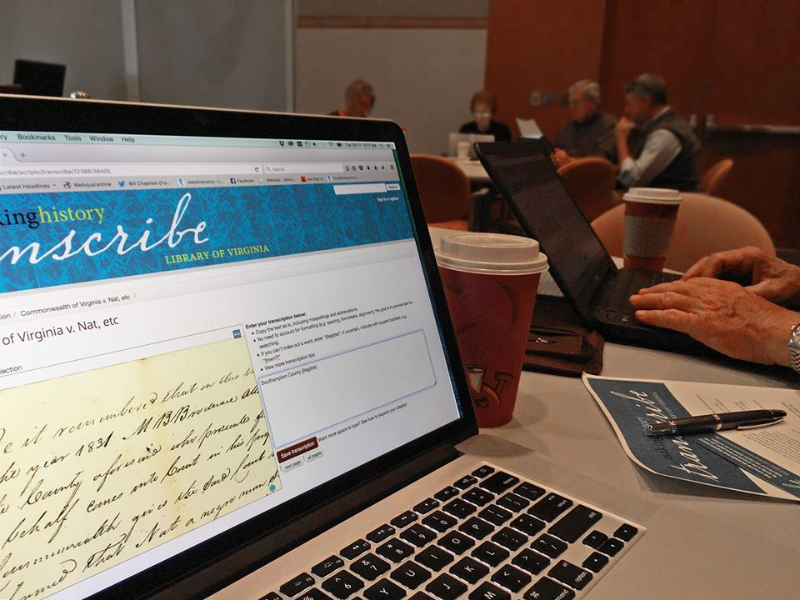

You can find transcribed copies of cases related to the Nat Turner uprising, including the commonwealth cause against Nat Turner, under the African American Narrative heading on our digital collections webpage. http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:8881/R/QINQ68G1FC5TBR6UQUTQYJEHANX8VM781Y2HB8HL88MADINB6A-00006?func=search

For additional archival sources on Turner and the uprising, please see our electronic finding aids at Virginia Heritage. http://search.vaheritage.org/vivaxtf/search?smode=simple. You can search “Nat Turner” and select Library of Virginia as the repository. You should get 15 results ranging from governors’ papers to local court records.

If you need any additional assistance with archival reference, you can call or email the Archives Reference staff at 804-692-3888 or archdesk@lva.virginia.gov.

Best of luck with your seminar paper and presentation.

Sincerely,

Vince Brooks