Talk about spooky! Although the 18th Amendment didn’t institute nation-wide prohibition in the U.S. until January 1920, Virginia banned alcohol at the stroke of midnight on Halloween in 1916. Virginia went dry as the result of a 1914 state-wide referendum, setting off a legislative process that culminated in the passage of the Mapp Law, which went into effect on 1 November 1916, forbidding Virginians from producing or selling—but not consuming—alcoholic beverages.

Though alcoholic consumption was commonplace in Virginia during its earliest days—especially since it was often safer than the water!—as the 19th century progressed, more and more segments of the population began to speak out against the evils of alcohol and overindulgence. The rise of the Temperance movement brought men and women alike to advocate personal policies of temperance or abstinence. Organizations like the Sons of Temperance, the Anti-Saloon League, or the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which opened its first Virginia chapter in 1882, sought to fill their membership rosters.

Early temperance organizations in the South initially had a hard time recruiting due to their association with abolitionist movements and the ‘northern invaders’ of the Civil War. Ongoing fears of African-American voters and their potential political power birthed fears of third parties and single-issue voters who could divide support for the existing parties that propped up white supremacy. In Virginia, the problem was resolved by the 1902 Constitution, which severely limited African American political power.

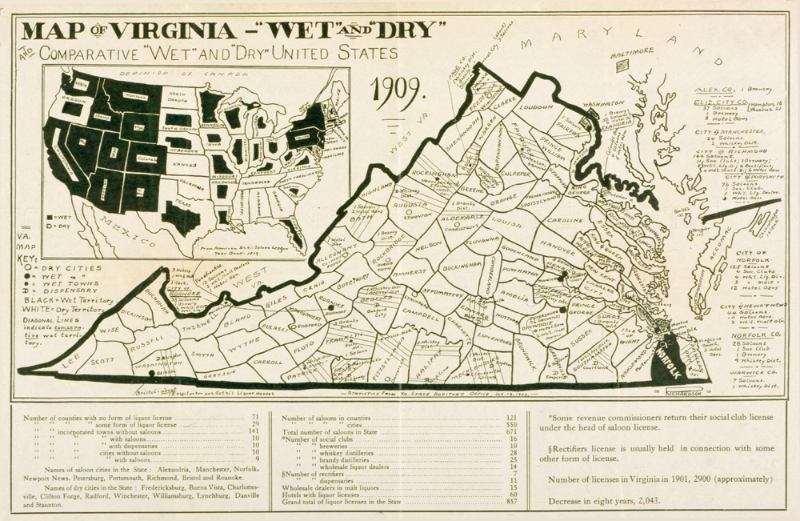

Although multiple attempts were made in the following decade to dry up Virginia, they were of mixed success. Localities could elect to ban alcohol, and many did. By 1909, 71 of Virginia’s hundred counties had no form of liquor license, and 141 incorporated towns had zero saloons—rural Virginia was practically dry. However, attempts at a referendum bill that would lead to state-wide prohibition were blocked by Senator Thomas S. Martin and his political organization, known as “the Ring”, in both 1910 and 1912.

In January 1914, the Williams Enabling Act passed the House of Delegates by a vote of 75-19, calling for a state-wide referendum. In the Senate, Martin was forced to capitulate due to the threat of a prospective third party that would compete against his political organization. Even so, the Senate vote ended in a tie that had to be broken by Lieutenant Governor J. Taylor Ellyson. The act, signed by Governor Henry C. Stuart, called for an election to be held on 22 September 1914. In a last ditch effort to scuttle the vote, Senator Walter Oliver of Fairfax worked in a qualification requiring 18,000 signatures from qualified voters to proceed. Dry supporters obtained 69,000.

In July, Stuart had writs of election sent out to the sheriffs and sergeants of the Commonwealth, and published notices in all of the major Virginia newspapers. Many Virginians, including moderate drys, supported the existing system of local option, under which individual towns and counties could make their own decision about prohibition. Opponents to a simple for or against vote argued that the proposed Prohibition law would violate local self-rule, as well as depriving the state of over $600,000 in revenue and thus leading to increased taxes. Brewery workers complained that the law would “destroy industries in which about one million and six hundred thousand men are employed directly.”

As the fight over Virginia prohibition geared up, newspapers and private citizens sent out a torrent of words arguing their position. Governor Stuart, who had pledged to sign the referendum bill as part of his campaign but who personally supported local-option, received an avalanche of letters—especially after the mostly wet major newspapers publicized his intention to vote against state wide prohibition.

Many of the complainants made reference to God and the Bible, casting opponents of state-wide prohibition as wicked sinners and “forces for evil.” These single-minded prohibitionists saw the fight against alcohol as a fight against all the evils of the world—violence, prostitution, poverty—and prayed that God would bring Stuart and other key public figures in line with their opinions. In contrast, their opponents were hindered by the success of dry educational efforts and propaganda. They could not argue for alcohol as being good in and of itself, in a state that was already largely dry. Instead, they focused on lost tax revenue and the preeminence of personal liberty and local rights.

Stuart did receive some letters of support for his position, mostly from other moderate drys who, like him, favored local-option and preservation of individual liberty. In the 1920s, William H. Stayton, the founder of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, would describe Prohibition as “desire of fanatics to meddle in other man’s affairs and to regulate the details of your lives and mine.

Check back tomorrow to see more about the aftermath of the 1914 referendum!

-Claire Radcliffe, State records archivist

Great post! A special thanks for the 1909 wet-dry map of Virginia.