“I was a race driver before I ever hit the track,” said Wendell Scott, the first African American to race NASCAR’s Grand National circuit, in a 1982 interview with the Richmond Times Dispatch. As a moonshine runner, Wendell Scott expertly skirted police on the winding country roads surrounding his Danville, Virginia home. In his own words, Scott proclaimed himself “the greatest moonshine runner of them all, dusting off deputies in a 1946 Packard loaded with jars full of white lightnin’ on a run between Danville, Va., and Charlotte, N.C.”[i]

During prohibition, bootleggers started modifying their cars to go faster and handle better than the cars pursuing them. Though prohibition ended in 1933, the South’s love of moonshine persisted, and so the time-honored custom of outrunning the police to transport illicit goods for profit continued.

It was out of the necessity for a speedy vehicle that stock car racing was born. “The need to prove who had the fastest car,” Suzanne Wise explains, “led to weekend races at tracks carved out of pastures and corn fields.”[ii]

And it was via moonshine running that Scott found his way to becoming a bonafide stock car racer. In the 1950s, the Dixie Circuit, a competitor of NASCAR, in an attempt to attract larger audiences to its Danville events, came up with the idea of adding a black driver to its field of exclusively white competitors.

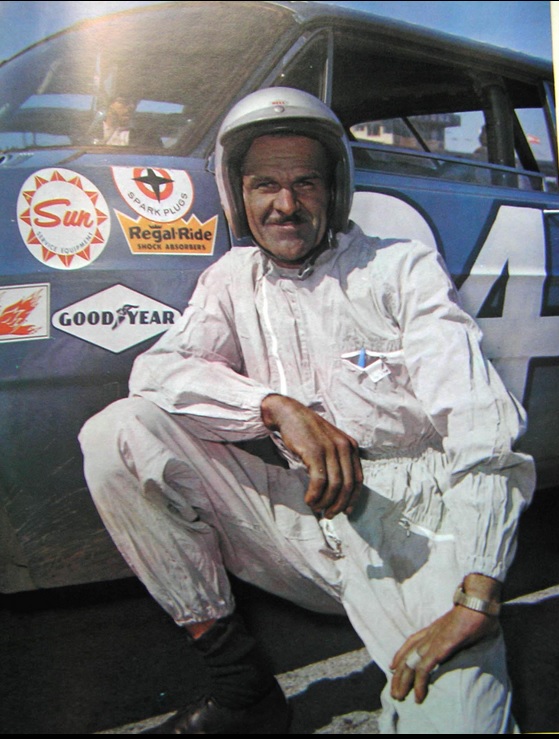

Running moonshine provided Scott with the skill he needed as a driver, but his mechanic’s knowledge would prove invaluable during his race career as well. As a child, Scott helped his father in his garage, growing into a skilled mechanic at a young age. As an adult, he transferred this knowledge into business and into his race cars. It proved instrumental in maintaining a career without the sponsorship his equally successful white peers enjoyed. Scott was able to achieve an impressive record in cars built with second hand parts, battling his way through the ranks before reaching the Grand National Circuit in 1961.[iv]

As the sole black driver in the segregated South, Scott faced what, to many, would have been insurmountable challenges. In the early years, fellow racers wanted to take him out, promoters treated him with contempt and spectators greeted him with a mixture of admiration and irreverence. “Give ‘em hell Wendell”

In 1963 Scott became the first African American to win a NASCAR sponsored event in Jacksonville, Florida. Though the article covering the race named Scott the winner, it offered no clue as to why it took two extra laps for the race to be called for driver Buck Baker. A “suspicious disqualification” was the ostensible reason Scott was not immediately given the checkered flag, but the more likely reason was that race organizers weren’t sure how to deal with the customary kiss given by a white beauty queen to the victor in the winner’s circle. Scott was declared the official winner a few hours after the race, but he never received a trophy for the win during his lifetime, an indignity which never left him. The incident exemplified both Scott’s skill as a driver and the terrible bigotry he faced in a sport he loved.[vi]

In 1973, after years of competing in cast-off race cars, Scott combined every resource he could muster to buy a truly competitive, first-class race car. The first race he ran in his no. 34 Ford Torino was at the infamous Talladega Speedway, located in Alabama and known as “The Big One” for the dizzying speeds that could be reached on its 2.6 mile track. As the narrator of a 1970s publicity film about Talladega dramatically explained, “Every race here is shrouded in a cocoon of tension and anxiety for the drivers and spectators alike.”[vii]

This particular race was shrouded in an even deeper tension for Scott and his family as everything was riding on it: Not only was he finally racing a car worthy of competition on a superspeedway, a car he had risked his life’s savings on, but Scott was required to shake hands with Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace before the race, adding to the drama and to his intense desire to prove himself.

“You know, sometimes you got to go all in,” his son reflected, “When they dropped that green flag. . .he was gone.” Scott began the race in 58th, passing eighteen cars in the first lap, but a terrible wreck occurred early in the race that left his car totaled, his body broken, and his competitive racing career done. Years later, when asked by a reporter if he wished he hadn’t raced at Talladega, Scott said he would do it all over again.[viii]

In 1977, the movie Greased Lightning was released, portraying Scott’s life “with typical Hollywood hyperbole.” Made with a big Hollywood budget, it starred Richard Pryor as Scott, Pam Grier as his wife and Beau Bridges as one of his pit crew, but Scott received very little in royalties from the film. “They promised me the sky,” he said, “but it wasn’t in writing.” The financial windfall he was promised on a handshake was never honored—yet another wrong, among many, he endured during his lifetime.[ix]

In October 2010, 47 years after Scott’s Grand National win in Florida and 20 years after his death, the Jacksonville Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame awarded his family a replica trophy for the win at Jacksonville’s Speedway Park. Graciously accepting the trophy, Scott’s wife and children took it to Wendell’s Virginia graveside to present it to him. “He will know it,” his son, Wendell Jr., said, “He wanted that trophy so much. Now he has it.”[x]

Footnotes

[i] Howard Owen, “Scott: Memories, Awards, Regrets,” Richmond Times Dispatch, June 13, 1982.

“Lightnin’ Fast Scott Recalls. . .,” Richmond Times Dispatch, July 7, 1975.

Pablo Julian Davis, “Virginia Vignettes: Who Was Wendell Scott?,” Smithfield Times, Aug. 8, 2007.

Wendell Scott will always be a legend when it comes to car racing. His story will forever be part of this world. Wendell has been an inspiration for many race care enthusiast.