It was Wet vs. Dry and City vs. Country and Dry Country won. It wasn’t even close. The advocates for Prohibition themselves might have been surprised by the disparity of the result–a win for Virginia prohibition by over thirty thousand votes–94,251 to 63,086. City drinkers likely peered into their empty glasses the evening of September 22, 1914, surer in the knowledge that legislation to ban liquor in the state would soon follow. And it did.

The Mapp Act passed and went into effect November 1, 1916. Virginia, then, had a head start of four years to the arrival of national prohibition.

The specific purpose of this blog entry is the encouragement of your physical presence at the Library of Virginia’s exhibit “Teetotalers & Moonshiners: Prohibition in Virginia, Distilled,” now open to the public. A hundred years after prohibition, we’re confidant you’ll depart with a different awareness of an unusual episode in the state’s history.

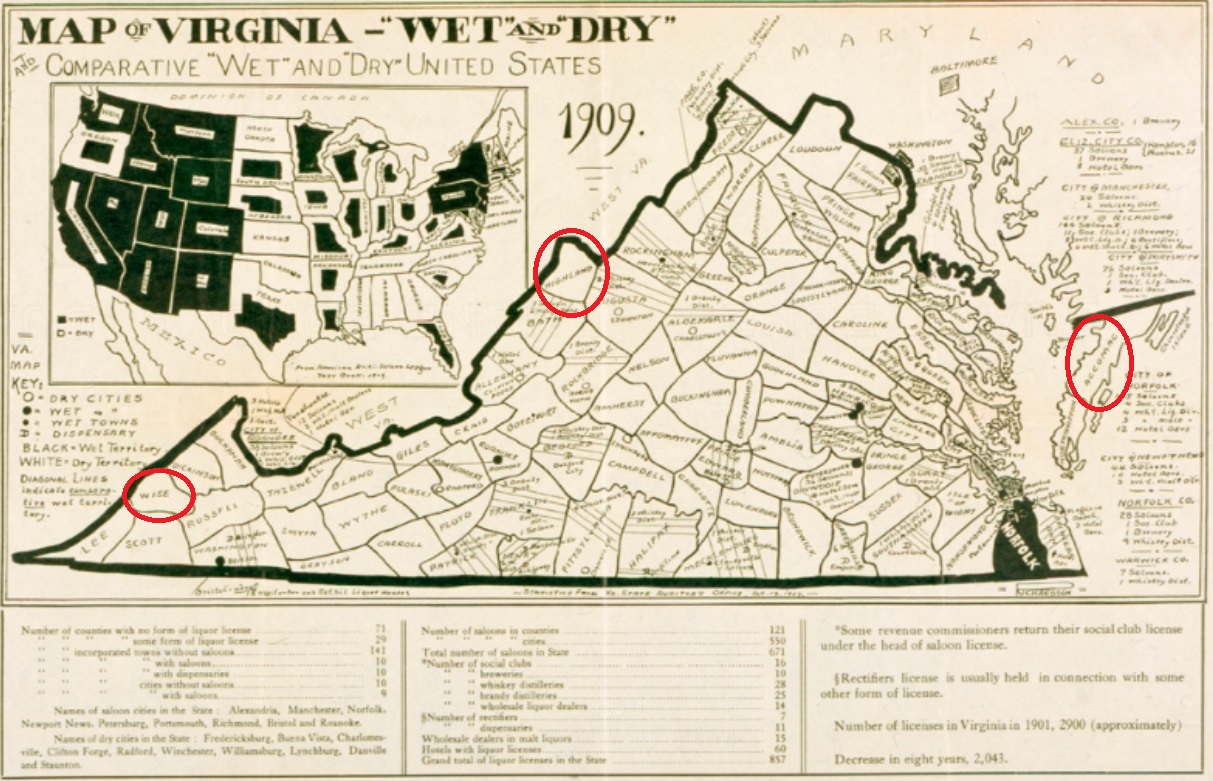

Each state in the Union took its own particular route to prohibition until the constitutional amendment of 1920. A key date in Virginia’s path was the approval of local option in 1886, allowing for a community or county’s voters to determine their stance on the sale and distribution of alcohol. The map above illustrates the camps and lines of the liquor divide. Note, for example, in a concentration of ink, Fort Norfolk, a seaside stronghold hostile to the dry life.

There was no shortage of political contentiousness in the run-up to the referendum. The very organized, determined drys, abetted by grassroots religious fervor, drove the issue to a dramatic reckoning by maneuvering to the statewide vote of 1914–one Waterloo of a loser for the wets. On the map, we circled the location of three rural newspapers that contributed to the rallying cry of the drys. Each image is pulled from the Newspaper Project’s digital archive, Virginia Chronicle.

The Highland Recorder of Monterey devotes most of its front page to the second month of war in Europe. On page two, the case is pressed for prohibition. We’ve isolated a few paragraphs here, to the right.

Observe the slyness in the lines above. If the prohibition referendum lost, would the local option of dry counties, like Highland, be overturned with their borders suddenly porous to drink? No. But to clarify the details of the referendum, to explain that dry counties could remain dry, might diminish the motivation of the anti-liquor faction to vote, and erase the opportunity to strike a blow against demon drink with passion and emphasis.

Crafty messages were being crafted on both sides and the craftiest messenger of all was James Cannon, leader of the Anti-Saloon League, a Bishop of second Methodist and an important political player profiled in the Library’s exhibit. The Big Stone Post invited him to their front page for the edition published prior to the referendum:

We excerpted above the sentence referring to $15,000 for purposes of voter persuasion.

Let’s make the reasonable assumption that an expenditure from this sum of $15,000 found its way to Accomac’s Peninsula Enterprise to purchase the following (to the right of the page), minus any attribution you’d see in a paper of today, in the September 19 issue. The same newspaper columns also appeared in the Enterprise’s rival, the Accomac News:

Remember, there were no polls to suggest the final result of the referendum. It’s very possible, given the passion aroused by the issue, rural voters required little influencing. The editors of the Recorder and Enterprise were startled by the margin of victory. Each paper published the results in their immediate coverage area. Click on the third image, for example, and you’ll see that a declaration of “one for the road” on Tangier Island will lead you nowhere fast:

The above statement: “There will be little difficulty enforcing the law with such a majority in favor of it,” reads as painfully naive in light of the proliferation of illegal activity in the referendum’s aftermath.

The artifacts, the folk history, and bureaucratic ruins of Virginia Prohibition, with its very real and inescapable difficulties, are curated for your study here at the Library of Virginia through December 5