From the earliest days of European settlement, Americans drank prodigious amounts of alcohol. Almost every aspect of early American economic and social life involved alcohol. Far from being seen as evil, alcohol was an essential element of the table, a stimulant for work, and a social lubricant for good fellowship—especially in a world where water purity was always in question. One estimate puts annual per capita consumption of alcohol at almost 4 gallons in 1830.

The temperance movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries grew as a reaction to the perceived overconsumption of alcohol. It was one of the longest lasting social reform movements in the United States and sought to radically change the way Americans consumed alcohol. Public support of the temperance movement was a major impetus for the 18th Amendment establishing national Prohibition. Followers of the temperance movement believed alcohol was to blame for societal problems like unemployment, crime, poverty, and domestic abuse.

Many women recognized the damaging effects of drinking on the family and worked through anti-liquor organizations and moral persuasion to regulate alcohol consumption. They supported the power of the state to curb drinking and alcohol, even as the state denied women an essential political right—voting. Instead, women who supported the temperance movement sponsored parades, established rooms stacked with prohibition literature, and canvassed for the prohibition vote. Involvement in the temperance movement was a legitimate way for women to enter the public sphere; in fact, many important suffragists got their start in the temperance movement.

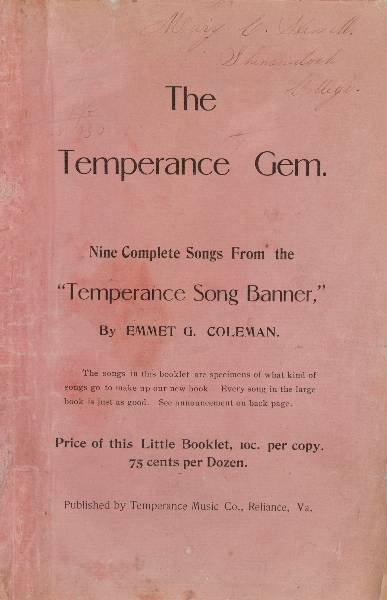

Participation in the temperance movement crossed gender, class, age, race, and religious barriers. Groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Anti-Saloon League, the Abstinence Society, the Independent Order of Good Templars, the National Prohibition Party, and the Sons of Temperance all carried the message of total abstinence from alcohol and encouraged political support for temperance reform using pamphlets, novels, newspapers, music, sermons, lectures, and art.

The images seen here are part of an eight part series called “The Bottle” by George Cruikshank. The series illustrates a family ravaged by effects of alcohol. The first image, titled “The Bottle is Brought Out for the First Time: The Husband Induces His Wife ‘Just to Take a Drop,’” is celebratory in nature; however, the middle images show the family’s decline, with the father losing his job and the family being forced to sell their possessions and beg in the street. The final image is titled “The bottle has done its work. It has destroyed the infant and the mother, it has brought the son and the daughter to vice and to the streets, and has left the father a hopeless maniac,” and shows the end result of alcohol’s ravages on the family and explains why temperance, and later prohibition, gained traction and became a political movement.

Teetotalers & Moonshiners: Prohibition in Virginia, Distilled, an exhibit running through 5 December 2017, tells the story of Virginia Prohibition and its legacy, including the establishment of Virginia’s Department of Alcohol Beverage Control and NASCAR. Newsreels of still-busting raids, music from the Jazz Age, and vintage stills complement the archival record of the exploits of Virginia’s Prohibition Commission. The exhibit is supported in part by the Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control and the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association, with Style Weekly as the print media sponsor. On Wednesday, 7 June 2017 at 12:00 PM, the Library will be hosting the event Liquor Lore: Enforcement Stories from the Virginia ABC. Retired and current Virginia ABC special agents will share stories from the exciting cases they’ve encountered during their careers and explore how their experiences compare to the tumultuous days of Prohibition. The event is sponsored by the Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control and is free and open to the public.

-Dana Puga, Prints & Photographs Collection Specialist

When I was a child, there was a small store on Colley Avenue in Norfolk that had very good ice cream cones. When we would go that way, Mother would stop and get us each a cone. Later she told me it was a bootlegger’s place and that she felt strange going in there. Maybe the ice cream was a front and having women and children come in in the afternoon gave them coverage.