When Petersburg’s coroner filled out the death certificate for farmer Lump Moore, he wrote a simple “no” in answer to the question, “Was disease or injury in any way related to occupation of deceased?” And it was true – farming had nothing to do with how Moore died. It was his other, less than legal, occupation that led to his death in early March 1931.

Lump Moore was a bootlegger and had been convicted twice of violating prohibition law. He was known to local law enforcement in Brunswick County as “a very bad man” who carried a shotgun. Moore had his gun with him the night of 27 February1 when five Special Police Officers found him and fellow moonshiners dismantling a still. After a bootlegger discovered the officers lying in ambush and raised the alarm, a firefight broke out. When it ended, Moore had shot Officer Leslie Daniel and Officer Norman Daniel had shot Moore.

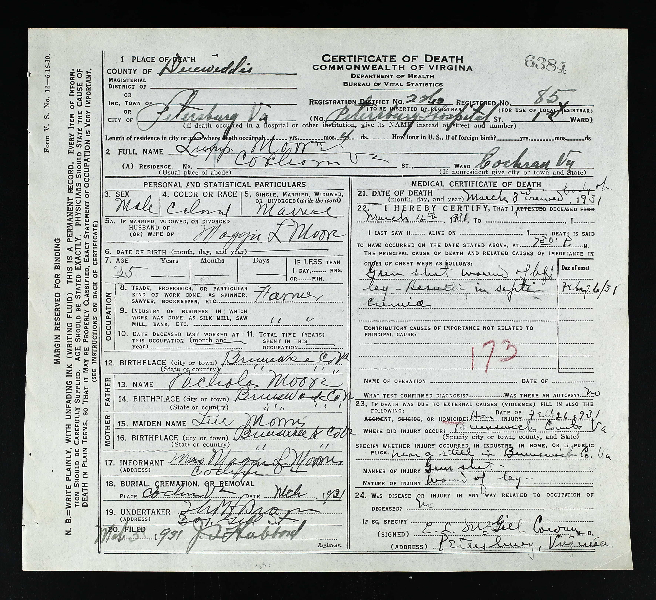

It was not a clean wound. Norman Daniel’s gun was loaded with buckshot, and the coroner’s postmortem examination noted that both bones in Moore’s left leg had been shattered. Moore did not die immediately, but the officers, in their haste to get Leslie Daniel to a doctor, left the injured bootlegger, covered “with some bags and blankets,” by the still site. They did not return for Moore until after sunrise the next day, when they took him to a doctor in nearby Lawrenceville. Moore was sent on to the hospital in Petersburg, where he died on 3 March of blood poisoning.

Lump Moore briefly made the news. The Richmond Times-Dispatch noted, in the article “Dry Officer Wounded in Brunswick County,” that “Lunk [sic] Moore, Negro” had also been shot and might lose his leg. However, shootings involving special police officers were not uncommon, and Moore’s death went unnoted a few days later. In one South Boston case that had “created some interest,” an African American man sued the prohibition officer who had shot him during a raid. The interest was not in the shooting but in the suit, which was deemed unusual.

“Old Lump Moore,” as the Brunswick County officers called him, was not, in fact, particularly old. On his draft card in 1918, his birth date was listed as 29 April 1884, which would have made him 47 at the time of his death (although his death certificate put him at 35). He was a tall and slender man, a farmer who spent most of his life in the small communities of Brunswick County, a rural Southside county bordering North Carolina.

Moore’s parents, Nick and Louisa, had been born in Brunswick County before the Civil War and the end of slavery. In census records they, like many of their neighbors, are recorded as being unable to read or write, although they owned their home and farm. By 1900 they have five children living at home in Red Oak, Virginia, although “Lump” is not listed among them. He may be James E. Moore, 10, as there was a son, J.E., whose birth in April 1885 was the closest registered to the draft card birthdate. Moore may also have been old enough at 15 or 16 to have left home by the time of the census.

In January 1911 Moore married Maggie Lewis, also a native of Brunswick County. The two appear in the 1920 census, living with two sons and two daughters in a cluster of Moores in Red Oak. Moore is described as a general farmer who owns a home under mortgage, and the census taker noted that he was unable to read or write, although he was comfortable enough to sign his draft card in 1918.

By 1930, the family had grown to include 9 children: Virginia, Elizabeth, Albert, Ashby, Alex H(orton), Sylvester, Maria (Marie Eva), Dorothy, and Ernest. The only person missing, in fact, is Lump Moore. Maggie is listed as the head of the household, and Lump’s whereabouts are unrecorded. Within a year, Lump Moore would be dead. The widowed Maggie would make her final appearance in the census in 1940, three years before her own death from heart disease at age 43.

When the Lump Moore of census records and vital statistics is compared with his relatives and neighbors, there is very little by which to distinguish him. His notability in death only serves to highlight how unassuming his life had been up to that point and how disruptive the cat-and-mouse game of bootlegging and enforcement could be for families and communities. Lump Moore is a good lesson in understanding that Virginia’s moonshiners did not fit one particular mold but came from many different counties and backgrounds, with no one particular path into bootlegging.

-Meghan Townes, Visual Studies Collection Registrar

I’ve always known the name and that “Lump Moore” was my Great Grandfather. I’ve heard tales about him all my life, but never have I read anything so trust worthy and real. Yes… I do believe this story. I saddens my heart but brings closure to the tale.

Lump Moore’s son “Sylvester Moore” is my Grandfather. If he were here today he would have Great, Great Grand Children. I miss my Grandfather dearly. God rest thier souls… Peace.

P.S. I appreciate this learning and encourage the public service to continue from every State.

I am also related to Lump Moore. He was also my GGG grandfather.

I am also related to Lump Moore. His daughter Maria (Marie Eva) is my grandmother. We have heard stories about Lump Moore so it’s nice to see more information here.

Lump Moore was my grandfather. My mother ( Marie) told me how he died. She was 9 when he was killed and didn’t know a lot of the details. This is eye opening. As a youngster growing up in brunswick Co. I vaguely remember meeting a Norman Daniels; the same man that shot him.