On 17 March 1856, the General Assembly adopted a law entitled, “An Act providing additional protection for the slave property of citizens of this commonwealth.” This legislation established a new inspection system to prevent the escape of criminals and enslaved people aboard commercial shipping vessels. All vessels bound for any northern port beyond the Virginia capes were subject to the inspection.

The Underground Railroad offered avenues to freedom for African Americans, some of which made use of Virginia’s extensive waterways. Free and enslaved African Americans provided an important labor force for the state’s thriving maritime economy. Employment along the busy wharves in Virginia’s harbors also presented enticing opportunities to escape. By the mid-1850s, many runaway slaves from the Hampton Roads area were suspected of escaping aboard ships destined for northern ports. One Norfolk newspaper described this alarming situation as “an intolerable evil.” Urgent pleas for a more effective system to stop these escapes were sent to Richmond. The General Assembly received strongly worded petitions from the citizens of Norfolk, Elizabeth City County, and Princess Anne County. These Tidewater localities wanted “additional legislation…which should clothe the Pilots of our state with power to search vessels, arrest fugitives, and should require every vessel bound to a Non-Slaveholding Port, to take a Pilot…to give us the necessary protection.” Soon, Delegate Francis Mallory of Norfolk introduced new legislation aimed at the inspection of northern-owned shipping. The act did not apply to vessels owned by Virginians, the United States government, or foreign countries. Due to these exemptions, the trans-Atlantic trade was not adversely affected by frequent inspections. While some steamships were targeted, the majority of vessels inspected were coastal sailing craft.

To coordinate this effort, Governor Henry A. Wise promptly appointed Dr. Jesse J. Simkins as the first Chief Inspector of Vessels. A prominent citizen of Northampton County, Simkins was a respected physician, president of the Norfolk Democratic Association, and a friend of the governor. He also enjoyed the respect of the Chesapeake Bay pilots, many of whom recommended his appointment. In addition, both Edward S. Gayle and James L. Adams received gubernatorial appointments as river inspectors. These men served under Simkins’s authority and were assigned to cover the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers. Eventually, 12 river inspectors and 35 pilots aboard six pilot boats conducted inspections until 1861. The Chesapeake Bay pilots, however, acted as the primary investigators. Two pilot boats regularly intercepted daily shipping and issued certificates to those vessels cleared for passage. Ship captains could be fined $500.00 if their vessel departed without receiving a certificate. Armed pilots vigorously enforced the new inspection law. In anticipation of resistance, they were empowered to command the local militia if additional force was needed. Governor Wise provided fifty muskets and two six-pounder cannons to inspectors in order to “make an escaping vessel which they cannot board heave to.” Although earning a fee of five dollars per vessel, strict penalties awaited any negligent inspector who allowed any uninspected vessel to leave Virginia’s waters.

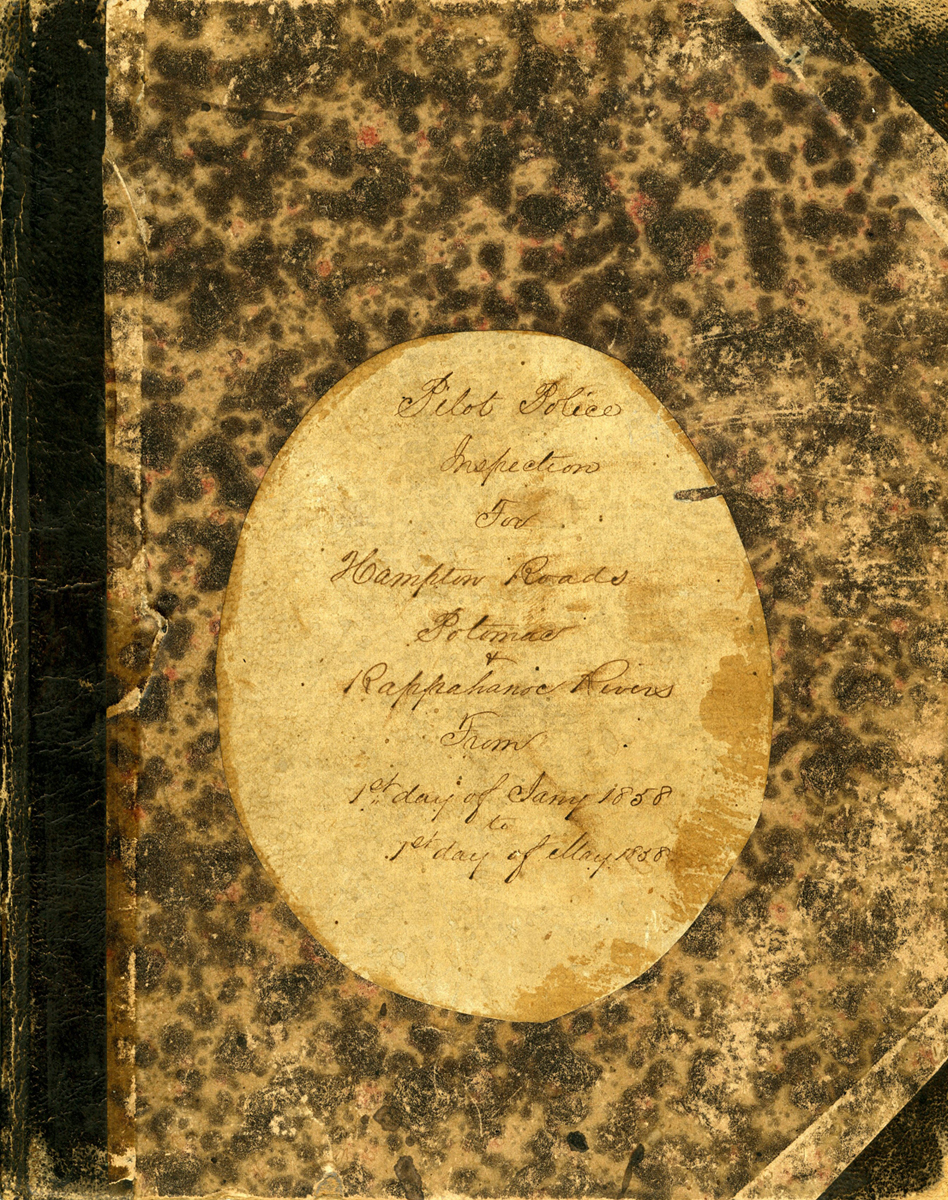

Chief Inspector Simkins, stationed at Norfolk, coordinated the inspections, tabulated the data, and submitted detailed quarterly reports to the governor. These reports, compiled into seventeen small ledgers, are arranged chronologically from October 1856 to March 1861. Each entry typically includes the inspection date, vessel name, homeport, destination, cargo, vessel owner, captain, and number of crew. By May 1858, the reports submitted by new chief inspector William H. Parker became noticeably more meticulous. They included more statistical tables that summarized the total number of vessels inspected, type of cargoes, amount of fines, and inspection fees received. Parker also provided a valuable list naming all the Virginia pilots who conducted the inspections. The chief inspector also kept careful records documenting the amount of oysters exported. Governor Wise was increasingly concerned with the uncontrolled harvesting of oysters from Chesapeake Bay. He hoped to convert the exportation of this important natural resource into state revenue by licensing those vessels permitted to remove oysters.

Violations of this new inspection law occurred frequently by captains who were either unaware or too stubbornly independent to allow their vessel to be boarded. Soon after the law took effect, on 8 April 1856, authorities seized the Cumberland Coal Company schooner MARYLAND. Elizabeth City County militia boarded the New York-based vessel, suspected of harboring escaped slaves, and the resistant captain and crew were jailed for failure to comply with the inspection. The surprised ship owners contemplated legal action, but Chief Inspector Simkins mediated a compromise allowing the schooner to depart after payment of a reduced $300.00 fine.

The advent of ship inspections did not completely prevent escape attempts. On 28 May 1858, an inspector discovered an enslaved man, Anthony, of Isle of Wight County, hidden beneath the deck of the New Jersey schooner FRANCIS FRENCH. Authorities quickly arrested Captain Thomas F. Loveland and his crew of five for attempted slave abduction. During the official court proceedings, the white crew members were spared a lengthy defense when a free African American crew member, William H. Thompson, confessed his involvement as the lone perpetrator. Thompson only intended to assist Anthony’s journey to visit his wife in Portsmouth. Harsh penalties, however, were established for assisting runaway enslaved persons and Thompson received the maximum sentence, ten years in the penitentiary. According to law, the ship owners forfeited the FRANCIS FRENCH to the Commonwealth of Virginia and the vessel was auctioned by the county sheriff. Just a few days later, another dramatic attempt occurred near Petersburg. Captain William B. Baylis of the schooner KEZIAH departed with a cargo of wheat destined for Wilmington, Delaware. When five enslaved people went missing, authorities suspected that their disappearance had been enabled by the captain of the two-masted schooner. Baylis was a successful conductor of the waterborne Underground Railroad, but this high risk adventure now ended. A steamboat was chartered to overtake the KEZIAH some thirty miles downstream. All five escapees were found hiding below decks and eventually returned to their owners. Captain Baylis was convicted in Petersburg Circuit Court on five charges of slave abduction and sentenced to serve a total of forty years in the penitentiary. Following his wife’s tireless efforts to gain his freedom, Baylis was released from prison in March 1865.

Vessel inspections ceased in 1861 soon after Virginia seceded from the Union. Its effectiveness in preventing the escape of enslaved persons was best expressed by Simkins in his report filed 17 June 1857: “The Inspectors seem to have been faithful in the discharge of their duties, and the operation of this new Law has been beneficial to an almost incalculable extent. The escape of slaves from tidewater Virginia to the North has now become very rare. Soon, the grievance will cease to exist.” Although the inspection system was originally intended as a method to control the enslaved population, these inspection records also provide a unique maritime register of more than thirteen thousand vessels plying the waterways of the Commonwealth.

-Tom Crew, Reference Archivist