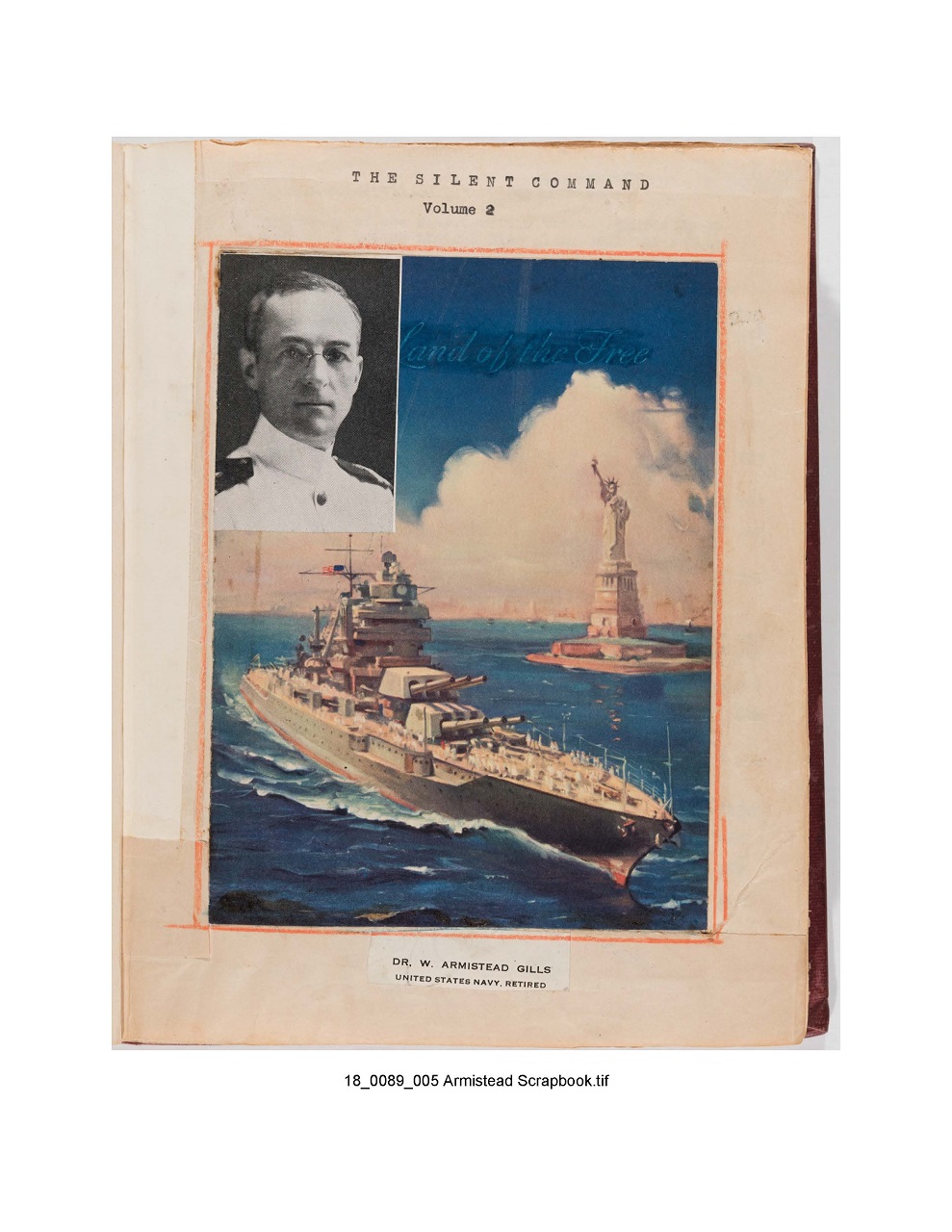

“Muzzled Doctors vs. Unmuzzled Guns” was a provocative phrase used by retired naval officer William Armistead Gills, M.D., to describe the poor condition of medical care for seamen during the first half of the twentieth century. Why would Gills, a World War I veteran and dedicated officer, pen such forceful criticism, hinting at military unpreparedness? A voluminous scrapbook and his War History Commission Questionnaire at the Library of Virginia reveal the details of this fascinating story.

A native of Amelia County, William Armistead Gills graduated from Richmond’s Medical College of Virginia in 1900. Demonstrating an affinity for the military, he served as a lieutenant in the Virginia National Guard medical corps for several years while attending the Army Medical School in Washington, D.C., from which he graduated in 1906. A faculty member at the Medical College of Virginia from 1904 to 1908, he served on the staff of Governor Claude Swanson. After serving in the United States Army medical reserve corps from 1910 to 1913 he entered private practice in Richmond.

With America’s entry into World War I in 1917, Gills enrolled as an assistant surgeon in the medical reserve corps. Commissioned a lieutenant, in October he was assigned to the U.S. naval base at Block Island, Rhode Island, where he directed the medical department.

In January 1919 the influenza pandemic struck the base and the coextensive town of New Shoreham. In addition to his responsibilities at the base, Gills assisted the one civilian physician in caring for New Shoreham’s 1,400 inhabitants. He received a commendation and the thanks of the town’s leaders.

Gills remained in the Navy following the war and was posted to the naval station at Newport, Rhode Island, where he served until December 1919, at which time he was transferred to Guam. In 1922 Gills became ill with fatigue, irritability, sleeplessness, nervousness, eye pain, and abdominal issues, which he believed were caused by the tropical climate. He requested a transfer, but a medical review board deemed him not sick, but a “malingerer” fit to serve. Gills was promptly sent back to active duty.

After much petitioning he was transferred to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Washington, D.C., and placed on the sick list. Despite his protests that he was truly ill, medical officers there described Gills as having experienced a “mild nervous breakdown.” Naval authorities eventually retired him in 1923 because of “physical disability not caused by military duty.” This designation was crucial as it resulted in reduced retirement pay.

In 1926 Gills completed a questionnaire sent by the Virginia War History Commission to gauge veterans’ experiences during the war. He commented on how much he liked the military and lamented how the general public paid little attention to “their navy” during peacetime. Still, despite his general satisfaction with his life in the service, we get a glimpse into his conflict with the navy as he described civilian life. “Since my retirement, I have been engaged wholly, in rewriting my manuscript . . . [related] to the improvement of the health and happiness of the personnel of the Navy, studying statistics, traveling, and writing communications incident to this work.”

True to his word, until his death in 1948 Gills lectured and wrote extensively about the dangers of antiquated medical care in the navy. Through what he described as a careful examination of naval facilities, he argued that the medical corps was staffed by untrained and incompetent recent medical school graduates not prepared for their daily responsibilities. He further asserted that there were too many “book-doctors” not given the latitude to develop novel treatments. Gills insisted that the general condition of naval personnel was substandard, as preventative measures were not in place, and that ill seamen often were deemed malingerers and sent back to active duty. These problems not only caused suffering (and even death) among seamen, but also compromised the navy’s effectiveness, “our first line of defense,” as he dramatically termed it.

Gills considered himself something of a pioneer in this pursuit. It is also evident that he felt persecuted, going back to his experiences in Guam. In addition to medical care issues, he sent a considerable amount of correspondence to military and civilian authorities seeking redress over the manner of his discharge, which he saw as an attempt to tarnish his service record. His voluminous scrapbook, acquired by the Library of Virginia, contains scores of letters, articles, and excerpts from manuscripts and his one published book, The Crew or the Cruiser (1933), that he sent to naval authorities, congressmen, and Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Not getting a satisfying response from President Roosevelt, Gills even sought the aid of First Lady Eleanor for a personal meeting.

Despite the decades-long conflict with the navy, he still felt a strong affinity for the armed services. His obituary in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, 24 November 1948, identified him as Lt. William Armistead Gills and noted that he was buried in Hollywood Cemetery with “military honors.”

–John G. Deal, Editor, Dictionary of Virginia Biography