In this age of no-fault divorce, it is hard to imagine that from 1776 to 1826 the only means of divorce in Virginia was by petitioning the General Assembly. Petitions on various subjects were the commonwealth’s main source of legislation in the antebellum era. County and city courts began to grant divorces in 1827, but until 1852 the state legislature still accepted petitions for divorce. During the years when the legislature was the only recourse for those seeking divorce, only a fifth of petitioners obtained a divorce or legal separation.

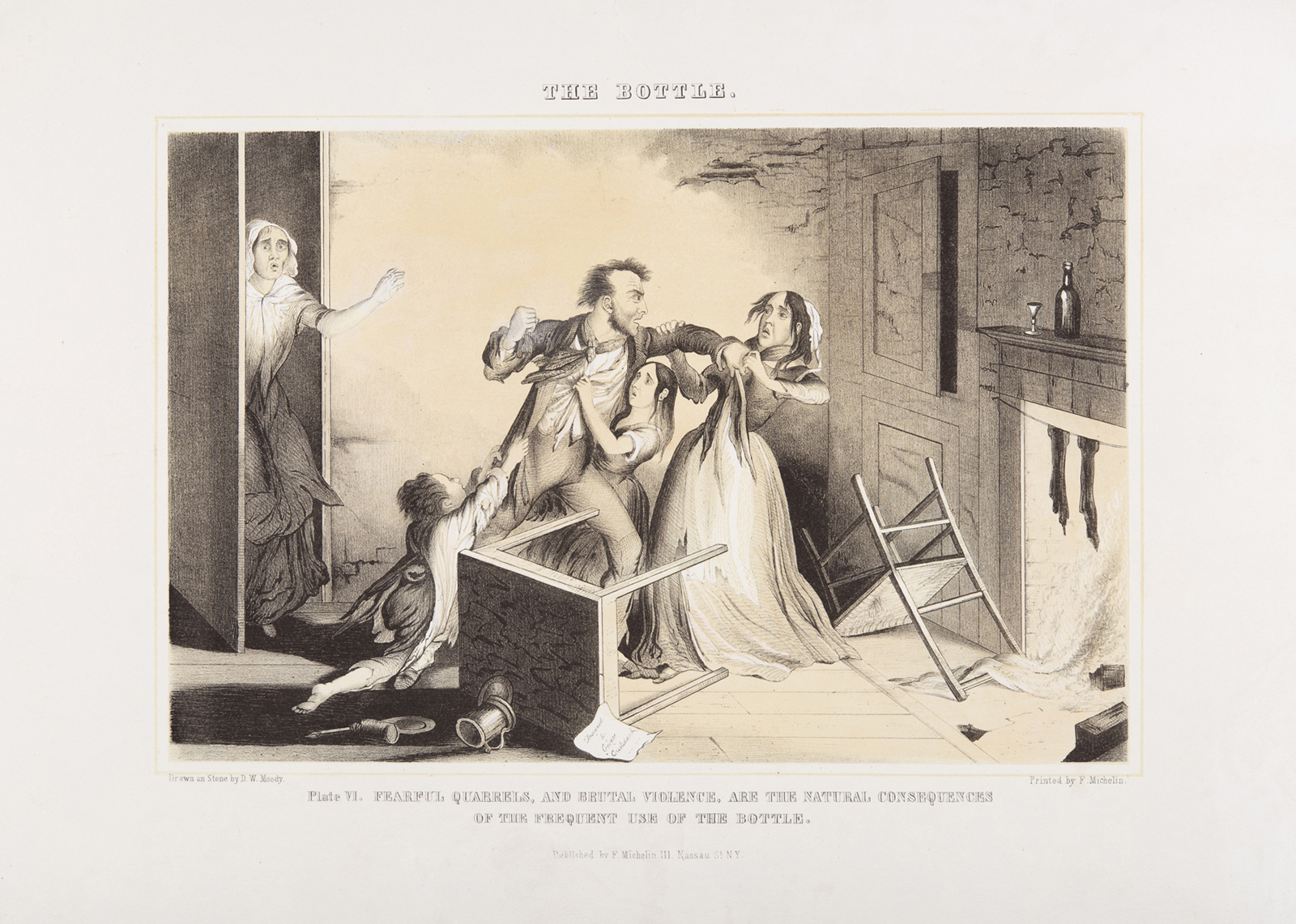

Today’s blog post looks at two divorce petitions to the General Assembly from Winchester residents. The first is from Amelia M. Alexander. The petition, presented to the House of Delegates on 13 December 1825 and filed under Frederick County, tells her tale of woe in language worthy of a novel of that day. “During the year 18[–] whilst she resided in the District of Columbia,” she had married John Alexander. “She was then young and knew naught of the sorrows of life; she was full of hope and full of joy. To poverty and its attendant miseries she had ever been a stranger … But alas! She has since too fatally discovered that lifes enchanted cup but sparkles at the brim. Disaster after disaster ensued.” Within a few months of marriage, she discovered that John was an abusive drunkard: “blows and bruizes were added when the brandy bottle raised his phrensy to its highest state … He would absent himself for months without making provision for her support.” Amelia’s father went bankrupt, and he and her younger sister moved in with the couple. Her husband visited “brothels of the town Bringing home to his own innocent and untainted wife, compelled to administer to his yet unsated passions, the shame and sorrow of his violated vows, and all other most horrid consequences.” To escape “the sin and shame brought on her,” she moved with her father and sister from Washington to Winchester in early 1824, supporting herself by working as a seamstress. John followed her to Winchester later that year, but was arrested for stealing goods worth $13.96 from “a certain George T. Lane” and served a year in the state penitentiary. Amelia feared that after his release from prison John would “wrest from her the pitiful earnings of her labours and her life.”

Accompanying the petition are court documents about John Alexander’s indictment and sentencing, affidavits from Winchester residents about Amelia’s good character and John’s bad reputation, and a doctor’s statement that he had treated Amelia for venereal disease and was confident she contracted it from her husband. Amelia had, in the words of her petition, “tasted the bitter cup of misery, and … drunk it to the dregs. Wether she shall be permitted to dash it from her lips, or constrained to consume the last particle, rests with your Honourable body whose justice and mercy she now abides.” The General Assembly did indeed show mercy by passing a bill of divorce.

The second petition, presented by Elizabeth Bowling of Winchester on 5 December 1843, is less flowery than that of Amelia Alexander, but appears to be equally heartfelt. Elizabeth stated that on 13 April 1836 she married Jeremiah Bowling, Jr., who was described as “a young mechanic of the town, whose parents were and still are respectable inhabitants of said town, and who as far as your petitioner had ever heard was himself a sober correct and industrious man.” However, Elizabeth found out “too late for her own happiness, that she had been cruelly deceived or grievously mistaken in his character.”

In August 1836, “without a word of complaint or a word of warning,” Jeremiah left town and never returned, “leaving his debts unpaid and leaving no provision whatever for your petitioner’s support.” On 5 May 1837, “about eight months after his departure,” Elizabeth gave birth to a daughter. “Your petitioner has occasionally heard of her husband during his long period of voluntary and unprovoked separation. It seems that after leaving Winchester he went to Wheeling [now in West Virginia]– thence to Rock Island Illinois, where it is said he remained a month and then got on board of a Coal Boat, bound for New Orleans.” She later learned that he had enlisted in the army and gone to Fort Adams, Mississippi. She wrote to him at Wheeling, Rock Island, and Fort Adams, but received no reply from him, although his brother in Rock Island confirmed that he was there but “engaged in no business,” and the postmaster at Fort Adams wrote that Jeremiah was there, “leading a ‘very trifling and dissolute life.’” This letter from the postmaster, received “about three years ago,” was Elizabeth’s last word of her husband’s whereabouts. She pleaded for the legislature “to release her from ties and obligations, which have been disregarded or outraged by a worthless Husband” who had left her “destitute and dependent [on the charity of her friends] for six long years of wretchedness.” Now that she had inherited property from her father, she wanted to make sure her husband would not return to claim it. However, the accompanying statement from Winchester citizens affirming that she was “a correct & respectable woman” bore only three signatures, despite her claim that “the whole population of Winchester” could vouch for her “correct and proper” behavior. Did Elizabeth’s neighbors perhaps suspect that someone other than Jeremiah was her child’s father? Whether for that reason or for some other, the General Assembly rejected her petition. In antebellum Virginia, breaking up was truly hard to do.

The Library of Virginia’s holdings of legislative petitions (1774-1865) have been digitized and are searchable by locality, topic, and name of the primary petitioner or other keyword at Virginia Memory.

-Bill Bynum, Reference Archivist

For further reading:

Buckley, Thomas E., The Great Catastrophe of My Life: Divorce in the Old Dominion. Chapel Hill: University of NC Press, 2002.