In the past few months, I have examined dozens of boxes of unprocessed Pittsylvania County court records dating back to the 1760s, searching for chancery causes for a future project. Most of the bundles appeared to have remained unopened since the day they were filed away over two centuries ago. Along the way, I discovered various documents that told the individual stories of people from different backgrounds that when brought together produced a integrated historical narrative of Pittsylvania County.

One box contained a bundle of declarations for Revolutionary War pensions filed in the Pittsylvania County Court. Declarations are narratives recorded by Revolutionary War veterans recounting their tours of duty fifty years earlier. One veteran named Lewis Ralph was 100-years-old at the time he filed his declaration in 1820. A native North Carolinian, Ralph enlisted in 1775 for a three-year term. He noted that he served “two years and a half a sargent [sic] under General Washington” and fought at the battles of Monmouth, Germantown, and Brandywine. He was discharged at West Point in 1778 and after the war moved to Pittsylvania County.

In a bundle of court papers dated 1811, I found the naturalization record of Alexander Brown. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Brown immigrated to the United States at the age of 18 in 1799. He initially resided in Petersburg where he worked as a clerk. Brown registered under the controversial immigration laws passed by Congress in 1798 known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. It increased the waiting period necessary for immigrants to become naturalized citizens in the United States from five to fourteen years. When Brown filed his original naturalization papers with the Pittsylvania County court in 1811, he was three years away from becoming an American citizen.

While examining the boxes, I periodically came across the stories of enslaved people seeking freedom. In 1788, a woman named Nann who claimed to be a free Native American filed suit for her freedom from John Worsham. Rosanna Johnson sued for her freedom in 1793 on the basis that she was brought into Virginia illegally from Maryland. Nancy Day sought her freedom in 1812 from Moses Hodges, claiming to be the daughter of a free white woman.

The records also contained numerous freedom certificates filed by free African Americans. In order to reside in the locality, free African Americans had to register with the local court. These certificates, or “free papers” as they were commonly called, recorded name, age, physical characteristics, and how the recipient obtained their freedom. One certificate tells how Frank Cousins, “a free man of color, a mullato of very bright complexion” was born free in Fluvanna County. In 1844, he moved to Lynchburg and registered. Upon moving to Pittsylvania County in 1850, Cousins filed his Lynchburg registration in the county court as proof of his freedom so that he could obtain his Pittsylvania County free papers.

The collection also includes correspondence and reports related to efforts made by women and local governments during the Civil War to meet the needs of soldiers in the field and their families at home. The Danville Ladies Soldiers Aid Society wrote a letter to the county court requesting that it appropriate funds so that they could provide “flannel undershirts, socks, &c” for every soldier from Pittsylvania County. The ladies were determined “to prosecute its labors so long as the war continued.” In 1864, a soldiers fund committee reported a plan to the county court to provide food to soldiers’ wives and children who were impoverished during the latter years of the war.

The Pittsylvania County court records are representative of the collections found at the Library of Virginia. They reveal that our history and our heritage are diverse. All races, nationalities, and genders contributed to the development of our collective heritage. To learn more about our history, plan a visit to the Library of Virginia or go to our digital collections site Virginia Memory.

This project was made possible through the Library of Virginia’s innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts.

–Greg Crawford, Local Records Program Manager

Are the unprocessed Pittsylvania court records being digitized for the website? If so, when? Thanks so much!

Ms. Williams,

After processing, indexing and conservation, the Pittsylvania Co chancery causes will be digitized as funding and staffing allow.

Do you need volunteers to help do this

I began to read these judgements, from the beginning, a few years ago for a project, since the chancery cases had not been pulled from the judgements. You are right, it didn’t look like they had ever been read! When I came across any genealogical information, I published it in the Magazine of Virginia Genealogy. I had planned to go until 1783 (when the tax lists started), but I had to stop before 1780. Pittsylvania is an exceedingly important county for learning migrations and other important information. I found migrations to NC, SC, GA and even to TN! Can the process of digitizing these chancery cases be expedited, please? This is one of the last counties to be processed, but, in my opinion, it should have been one of the first to be processed. Thanks.

This is great news Greg!

Help please! Where was the courthouse in 1767? Any information about a Mr. Robbert, innkeeper at “Pittsylvania courthouse” at that time?

Thanks, Audrey

Ms. Apple,

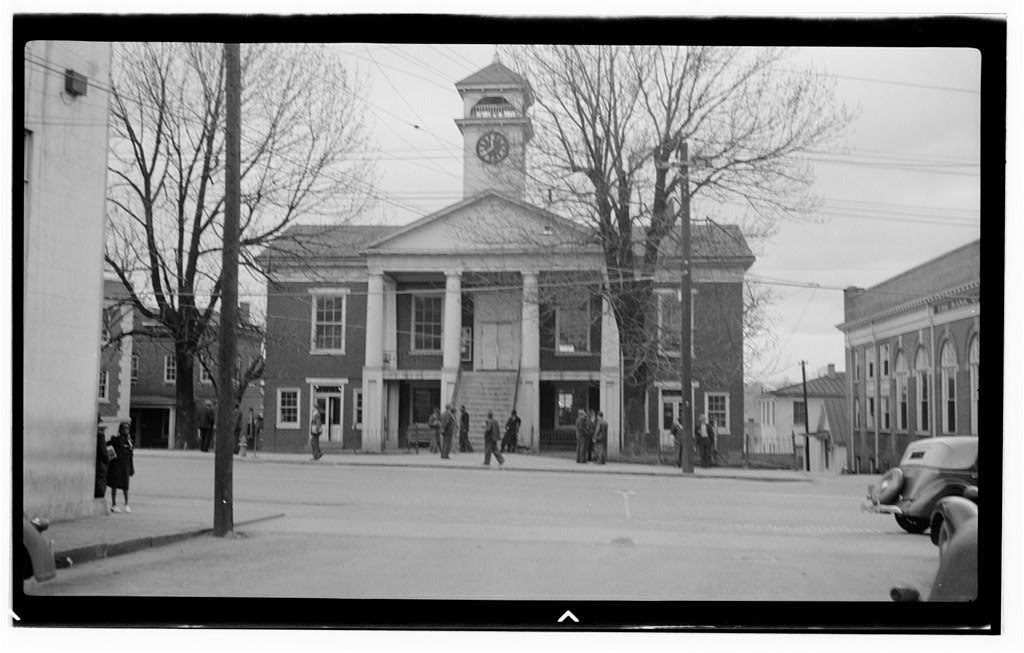

According to Carl Lounsury’s book “The Courthouses of Early Virginia,” James Roberts built the first Pittsylvania Co. courthouse in 1767 modeled after the Halifax Co. courthouse. At that time, the county seat for Pittsylvania Co. was in Callands.

Please get these records digitized before they are lost by fire or some other reason.