In the spring of 1905, a half-mile from the Norfolk city limits, the Boer War Spectacle (also called the Transvaal Spectacle or Anglo-Boer War Historical Libretto) was set to commence. First, however, there was the matter of some local government fees. Norfolk County chancery cause, 1907-055, Boer War Spectacle] v. S.W. Lyons, etc, details the ensuing conflict.

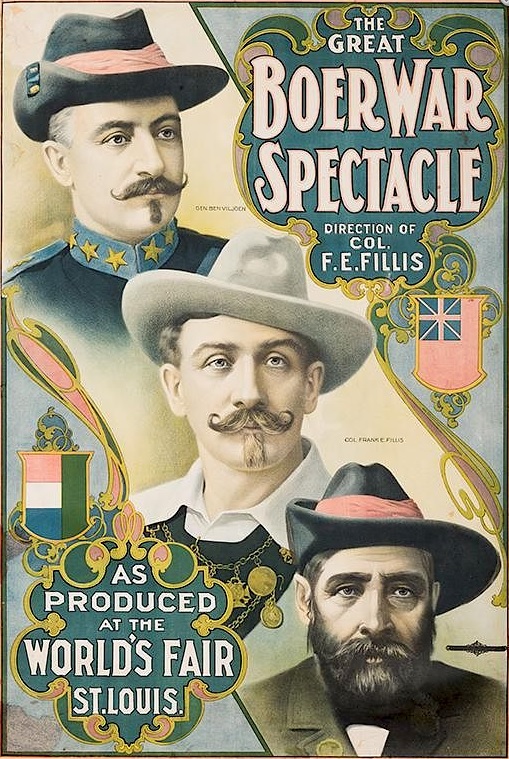

Chartered as a corporation in Missouri, the historical reenactment troupe was under the direction of Frank E. Fillis, a famous South African organizer and showman. Fillis sold this ambitious exhibition as “the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world.”

The idea was born near the Boer War’s end. While sitting around camp discussing news of the upcoming world’s fair, Major Charles Joseph Ross originally came up with the idea for the spectacle. A Canadian scout serving with the British, Ross hoped to capitalize on the fair’s expected popularity. As general manager, he hired artillery captain Arthur Waldo Lewis, who assembled British and Boer veterans to restage the pivotal battles of Colenso and Paardeberg. An advertisement appeared in Johannesburg’s Rand Daily Mail on 1 March 1904, entitled “Boer War Exhibition A chance for the unemployed!”

Over 600 veterans, including a contingent of native black South Africans from various ethnic groups, in particular the Tswana, and a pair of notable generals from the war, set sail for the United States with one shared purpose: “to earn a living after a protracted war of attrition.”

As host city to the 1904 World’s Fair, St. Louis was the embodiment of the nation’s cultural and economic progress, so much so that it managed to wrest hosting responsibilities for the Summer Olympics from rival Chicago. Archival research in the late 1990s revealed a significant outcome of this dual-hosting responsibility on Olympic history.

In August 1904, after an earlier ethnocentric white supremacist display by the Expo dubbed “Anthropology Days,” in which the so-called “savage tribes” put on pseudo-athletic displays, the Olympic organizers invited Jan Mashiane and Len Taunyane, Tswana dispatch runners from the Western Transvaal region, to participate in the men’s marathon. Despite a somewhat absurd race, both in course and conduct, the men are now credited as the first black South African Olympians.

After the World’s Fair and the Olympics, the Boer War Spectacle hit the road. Kansas City, Missouri’s Convention Hall was its first stop on 6 December 1904. The show went on to play Chicago, New Orleans, and several cities in North and South Carolina. Alongside the huge contingent of reenactors, the show brought along 350 horses, South African oxen, Missouri mules, transport and ambulance wagons, twelve large cannons, ten rapid-fire guns, ammunition, provisions, cooking utensils, surgical supplies, and a portable grandstand which sat ten thousand. Purportedly, the show was “the largest amusement production ever moved through the country” and required a special train. By the spring (24- 25 April 1905), the production arrived in Norfolk County (now Chesapeake) after the cancellation of shows in Petersburg.

The Norfolk County chancery cause was borne over a fee and licensing dispute with county officials S.W. Lyons, County Treasurer, and John D. Moore, Commissioner of Revenue. Lyons demanded a license tax fee of a hundred dollars per performance (there were two) and Moore demanded five percent of the gross receipts. A refusal to comply with these requests would have initiated a seizure of the production’s goods and chattels. The corporation opted to pay the amounts requested, but filed a lawsuit calling the county’s actions “unjust, illegal and without warrant of law.” The dispute was finally resolved in February 1907 in favor of the Boer War Spectacle. The show had moved on to Richmond (26-27 April 1905) and Staunton (29 April 1905) where crowds embraced “the show’s echoes of the Civil War” with its themes of estrangement and reconciliation. Thanks in part to the spectacle, sympathy for the Boers was widespread in the United States.

After the lawsuit and low turnouts, the show needed help economically. New York showman William Aloysius Brady had a plan. He provided the money to put on “the greatest staged spectacle” at Coney Island in May 1905. The show covered a 14-acre arena and required more than a mile of scenery, showing the South African landscape. Tinsmiths soldered a huge zinc trough for the show’s finale: the surrender of Boer leader, General Cronje, and his troops. The show added a detachment of veterans of the Irish Brigade who had fought with the Boers.

Brady’s Brighton Beach Development Company was responsible for the beginnings of Coney Island. The Boer War Spectacle was a part of that along with 150 other minor amusement features. Eventually, public interest in the spectacle began to wane. On 5 September 1905, according to a report in the New-York Tribune, a court-appointed sheriff “[seized] the costly spectacle.” With nowhere else to go, a group of 200 Boers took up residence nearby until the end of September. On 13 October 1905, the last man standing took his leave of the property and the show was officially disbanded.

The scanning of the Norfolk County chancery causes, 1718-1913, is now complete and the images are freely available online. The project was made possible by funding from the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA) which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts. The $104,000 project is the 69th digital chancery collection to be added to the Chancery Records Index.

Chronicling America and Virginia Chronicle were invaluable resources for researching this blog topic.

–Callie Freed, Local Records Archivist