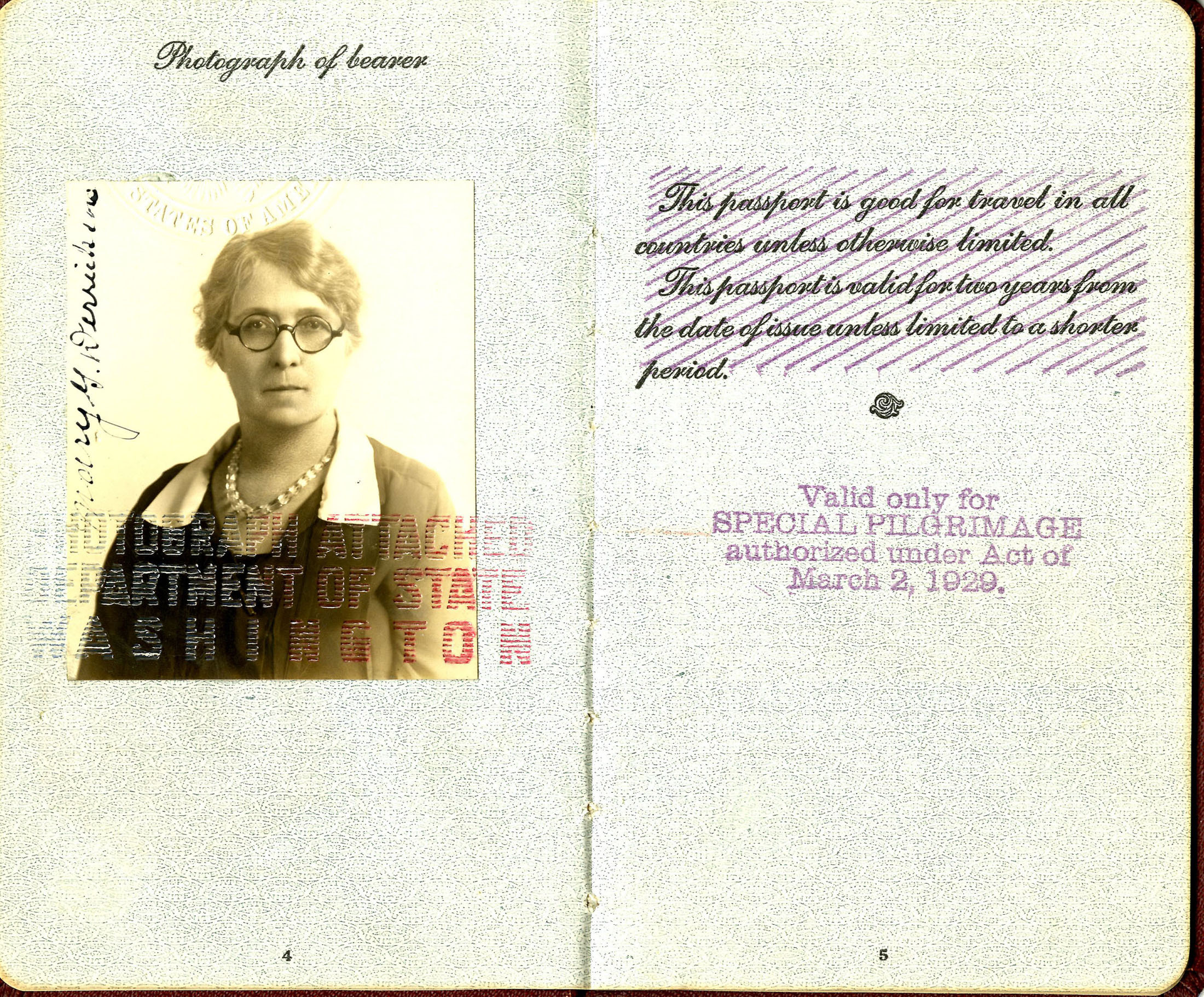

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in slightly altered form in the Summer 2001 issue of “Virginia Cavalcade.” The images are taken from two private papers collections acquired after the article’s original publication. Mary Derrickson and Carrie Elizabeth Alborn Perry both traveled to France in 1930 to visit the graves of their sons.

On 23 February 1920, Annie Lam of Covington, Virginia, wrote to the U.S. adjutant general about her son, Sergeant Bedford C. Lam, who had been a member of the Virginia National Guard.

“Nearly one year ago you sent me a card to fill out as to what deposition I wanted made of the body, of my son who died in Camp Hospital No. 10 Aug 1st 1918… I sometimes feel like I would rather not have his body moved and am writing to ask if you think the Government will in any way aid the mothers to go to the graves of their sons if they consent to leave them ‘over there.’” Lam ultimately chose to leave Bedford’s remains in Saint-Mihiel American Cemetery, near Thiaucourt, France. On 9 July 1930, she sailed to Europe to visit her son’s grave on a pilgrimage of Gold Star Mothers and Widows, as she had foreshadowed in her letter ten years earlier.

Over a three-year period beginning in the spring of 1930, thousands of American women whose sons or husbands died in Europe during World War I made the same pilgrimage. The federal government paid their travel expenses, the result of legislation that Congress enacted on 2 March 1929. The act directed the War Department to issue invitations to all mothers and widows of U.S. military members who had died in service between 5 April 1917 and 1 July 1921 and who were interred in European cemeteries. The national Gold Star Mothers’ Association, which lobbied for the legislation, considered the maternal relationship to be the primary one, with the marital bond coming in second and the paternal tie a distant third. The government eventually extended the courtesy to the survivors of those who died or were buried at sea, in both known and unknown locations.

Each eligible mother or widow received one all-expense-paid trip between May 1930 and October 1933. Of the 11,440 women entitled to take the trip, 6,730 wanted to visit the cemeteries, at an estimated cost of $840 per person.

For many women, the invitation to visit the graves of loved ones followed years of correspondence with the Graves Registration Service and its parent agency, the Office of the Quartermaster General. Helen Wylie Conrad of Winchester, the widow of Captain Robert Young Conrad, kept up a frequent exchange of letters with the two agencies from 1918 to 1933. Her husband had been killed on 8 October 1918 while leading his unit during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Many women faced an agonizing decision: whether to have their loved one’s body returned to the United States or left in foreign soil. “I want to bring my husband home to me as soon as it is permitted[.] [H]ow is that arranged?” Helen Conrad wrote to a Major Pierce on 5 November 1918. She was three months away from delivering the Conrads’ only child. “I also wish to attend to the whole thing myself and no one in the world, has my permission to do anything about it—can I be reassured on this point? That nothing, nothing will be done without my permission in writing?” She eventually changed her mind and left her husband’s body in a cemetery on private land, La Cimetiere de Glorieux in Verdun, France.

Initially, soldiers were buried where they died. In Robert Conrad’s case, his grave marker and body both bore identification, and a bottle at the head of the grave contained his home address, rank, organization, and death date. Second Lieutenant David B. Harris, a Richmonder who served with the 20th Aero Squadron, apparently was shot down behind German lines in the last days of September 1918. In a German military cemetery at Pierrepont, grave-digger Nicholas Wiebener buried him with the U.S. Army’s assurance that Harris’s parents “would recompense him for the upkeep of his grave, such as flowers, ferns, etc.,” according to Harris’s file with the Graves Registration Service.

As the years passed, France, in particular, wanted to consolidate the graves of soldiers, as so much of the country had become both battlefield and graveyard. In 1926, the owners reclaimed La Cimetiere de Glorieux and all bodies, including Robert Conrad’s, had to be moved. Helen Conrad was willing to buy the plot but was apparently unsuccessful. Therefore, in November she sent her husband’s friend and comrade, Major Robert Barton, Jr., to supervise the transfer of Conrad’s remains to the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. On 15 May 1919, David Harris’s remains were disinterred and reburied at Saint-Mihiel American Cemetery. Eleven years later, on 9 July 1930, his mother, Mary Taylor Harris, left New York on the SS President Harding with Party K of Gold Star Mothers and Widows, bound for Saint-Mihiel.

The quartermaster corps made enormous preparations for the visits. First, the office queried the known next-of-kin of each soldier for the name of the mother or surviving spouse. When the post office was unable to deliver the letters, the army referred those cases to the Veterans’ Bureau, which contacted the persons drawing the deceased soldiers’ benefits. In addition, local chapters of veterans’ associations and other patriotic organizations disseminated information about the pilgrimages.

Once the quartermaster corps identified an eligible woman, it asked her to respond to the 1929 survey asking if she might like to make the pilgrimage. Grace Hamilton Hicks, the director of St. John the Baptist Mission at Ivy Depot, Virginia, was the widow of Dr. John Ravenswood Hicks, a surgeon attached to the 302nd Tank Corps. He died of pneumonia on 3 January 1919 at Langres, Haute-Marne. She had been so busy with mission work that she had twice neglected to reply. On 1 October 1929, she finally told the quartermaster general, “I am very appreciative of this opportunity to visit the grave of my husband … at Thiancourt, and hope I shall be able to do so.”

Some women chose to forego the trip. Winchester’s Helen Conrad wanted the government to reimburse her for an independent trip with her eleven-year-old daughter, who had been born after Robert Conrad’s death. Senator Millard H. Tydings, of Maryland, even intervened on her behalf (Mrs. Conrad was originally from Baltimore). The quartermaster corps declined Conrad’s request, telling Tydings it was impossible to make such individual arrangements, as all women had to travel in groups, but that Conrad could probably pay the steamship line for her daughter’s travel. She apparently rejected the suggestion and never did make the official trip.

Once a woman responded in the affirmative, the quartermaster general’s office assigned her to a party. Women from the same state usually traveled together. Hicks initially was assigned to the same 9 July 1930 party along with Lam, Harris, and other Virginia women, but she asked to have her travel postponed. The office assigned her to a group leaving 27 August.

The quartermaster general also arranged with the steamship companies for round-trip transportation from New York to Europe, prepared schedules, and secured passports and travel documents. The government supplied each woman with a return ticket from New York to her home, including a lower-berth sleeping car on the train if her trip required overnight travel, a per diem allowance of $5 for the travel days she was alone, and an identification badge. After her 1930 trip, Grace Hicks dutifully returned the unused portion of her per diem, $3.58. An army officer sent back her money order with a kind note.

While the mission of the pilgrimage was sober, no one wanted the trip to be morbid. Accordingly, the government arranged tours for the women in New York, Paris, and London. In New York, Gray Line Motor Tours ferried them to prominent sites, including a visit to Coney Island on the return leg of the trip. Colonel A. E. Williams, of the quartermaster corps, reported after one pilgrimage in 1930 that the activities had a “splendid effect on their morale.”

The quartermaster general was greatly concerned with medical treatment for the pilgrims. The women’s ages averaged between sixty-one and sixty-five, considered elderly for females of the time. The older women may have worried about their physical ability to withstand the rigors of the trip. Accordingly, in 1930, Colonel Richard T. Ellis, one of the officers in charge in Paris, requested that key medical personnel remain with the program over the winter to help during the 1931 pilgrimages. “The tendency of pilgrims to conceal their condition (due to fear of not being allowed to visit the grave of their relatives) has in a great measure been overcome by a most sympathetic and understanding medical and nursing personnel,” he wrote. “The psychological reaction of the pilgrims resulting from the constant presence of a trained nurse, who frequently acts as a companion, is most favorable and cannot be overestimated.”

The quartermaster general encouraged mothers to participate even if they were in less than perfect condition. Sarah J. Inman, of Danville, declined the offer to visit her son’s grave at Oise-Aisne Cemetery on the grounds of poor health. Her son, Corporal Samuel J. Inman, Jr., had been killed by high explosives at nearby Soissons on 18 July 1918. In 1932, Captain A. D. Hughes, of the quartermaster corps, wrote to Mrs. Inman: “During the past two years many mothers who were in poor health and of advanced age made the pilgrimage and appeared to have benefited by the sea air and the excellent care they received… Should you make a pilgrimage you are assured that…everything possible for your comfort and welfare will be provided.” Despite Hughes’ encouragement, Inman did not make the journey.

If a woman became ill on the trip, the attending nurse or doctor filled out a medical card for her. Common complaints, duly recorded on medical cards in best government fashion, included indigestion, exhaustion, constipation, nervousness, and “mal de mer” (seasickness). When Etta L. Ferguson, of Roanoke, complained of indigestion, stomachache, exhaustion, and pain while breathing, a doctor wrote, “Mother seems lonely & homesick complaining of no appetite.” The physician prescribed “Sel de Hunt,” “Hepatic Salts,” and two doses of brandy. Soon Ferguson was “much brighter and happier.”

Ferguson was the first Gold Star mother from Roanoke to apply for a trip to the cemeteries. Her son, William Bertil Ferguson, had served as an apprentice seaman on the USS Lake Moor. He was one of forty-six crewmembers lost at sea when a German submarine torpedoed the ship three miles off Corsewall Point, Scotland, on 11 April 1918. Etta Ferguson sailed on 27 May 1931 aboard the SS President Roosevelt.

While each party’s pilgrimage varied somewhat, the trip of Ferguson and Party D was typical. After nine days at sea, they arrived at Cherbourg on 4 June 1931. Upon disembarking, the party left for Paris, where their liaison met them and settled them into their hotel. Their French hosts treated the American women with the utmost respect and deference. They spent four days in Paris, with plenty of time allotted each day for shopping, resting, and dining. On the first full day, they attended a ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, to lay a wreath at France’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, followed by a reception at the Restaurant Laurent attended by French war mothers, government officials, and prominent civilians.

On 9 June, the pilgrims left Paris for Verdun. The party visited several World War I battle sites and cemeteries, including Montsec, Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, Brieulles-sur-Meuse, the west bank of the Meuse River, Consenvoye, Fort Douaumont, the Trench of the Bayonets (where French soldiers reportedly had been buried with their bayonet blades protruding above the soil), and the Ossuary Loop.

When the women finally reached the cemeteries, they found no pomp or fuss, just simple courtesy and respect. A cemetery staff member showed them individually to the graves, supplied wreaths or flowers, and took photographs. At the cemeteries of Saint-Mihiel, Oise-Aisne, and Meuse-Argonne, the quartermaster corps built pleasant facilities in which the women could rest and refresh themselves. General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, served as the chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission in his retirement and bore a great deal of responsibility for the creation, design, and quality of the American cemeteries in Europe. The haphazard marking of Civil War battlefields greatly influenced the coordinated work of Pershing and the commission. The general played a major role in the selection of the headstone designs: crosses for Christians and Stars of David for Jews. Pershing also insisted that all cemeteries have chapels for visiting relatives.

Robert Barton Jr., who oversaw the 1926 reburial of his friend Robert Conrad in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, was impressed with its appearance. He wished “it were possible for the relatives of every American who lies on French soil to visit the American Cemeteries, to see their beauty and to observe the consideration shown them by the Americans in charge and the French people.” The women of the pilgrimages made the most of such a meaningful opportunity.

On 12 June, after their time at the cemeteries, the women of Party D began their return trip. They left Verdun and headed back to Paris via Sainte-Menehould, Suippes, Reims, and Château-Thierry. In Paris, they visited the Louvre. On 14 June, the group left for London, where they toured the Tower of London, St. Paul’s Cathedral, the nearby town of Richmond, and Hampton Court. On 16 June, Etta Ferguson visited Brookwood Cemetery, the location of the memorial for navy men—like her son—lost at sea. They spent the last full day in London sightseeing, visiting Westminster Abbey, and shopping. On 17 June, Party D sailed for the United States.

While the United States treated all of the women with respect, it did not treat all of them equally. Like the rest of American society at the time, the pilgrimages were segregated by race, with the African American mothers and widows staying in different hotels and on smaller, less luxurious ships. In the summer of 1930, the Nation magazine wrote a scathing indictment of the War Department: “There is no record, so far as we know, that any officer in the late war refused a Negro soldier the inestimable privilege of dying for his country because of his color. ‘No, Mr. Johnson, you will not go over the top today; today is the day for the Randolphs of Virginia to make the supreme sacrifice.’ If remarks such as these were ever uttered while the United States fought the Germans, we do not recall having seen them in print.” The magazine called the treatment of the black women an “incredibly stupid and ungracious gesture…Their black sons died as white men die.”

Party E, the third group of African American mothers to sail, included Emma J. Johnson Parker, of Franklin. Her son, Prince Algernon Johnson, was a student at Howard University when he enlisted. He served as a cabin steward aboard the USS Lake Moor (along with William Ferguson) when it went down on 11 April 1918, just two months after his marriage. Unlike Etta Ferguson’s son, who was lost at sea, Johnson was rescued and taken to Scotland, where he died from exposure the same day. His mother was one of three women chosen to represent the party throughout the trip, as was the custom for all the groups. The selected mothers received Gold Star medallions acknowledging the loss of their sons and commemorating their trip.

As with previous groups of black women, their accommodations were separate and unequal. In New York, they stayed at the black-only YWCA on West 137th Street. The white women had stayed at hotels such as the Hotel Pennsylvania and Hotel Astor. “There were no echoes of the criticism hurled at the government last year when the first two contingents were ordered to take boats on which no white women sailed,” reported the Norfolk Journal and Guide on 6 June 1931. “On Friday there were no white faces, but no voices thundered denunciation of the segregated plan.”

Like the women in Etta Ferguson’s party, the widows and mothers of Party E enjoyed suitable entertainment and activities during their trip. Colonel F. H. Pope, a quartermaster corps officer who led Party E, reported their visits to the major tourist sites in New York City such as “the Theatrical District, the East Side, the Ghetto and Bowery, the Financial District, Wall Street, the Exchange and Curb Markets, and …at the Battery to visit the Aquarium and view the Statue of Liberty.” The women expressed “sincere appreciation…for this form of entertainment and it was especially enjoyable to many who had never seen cities of like magnitude.” The New York Bible Society gave the women copies of the New Testament, and nearly all of the pilgrims attended a demonstration of swimming and diving at the YWCA. They “were very much pleased with the exposition,” reported Pope.

The ceremonies accompanying their 29 May 1931 departure for Europe were memorable. The city of New York presented U.S. flags to each mother and widow as she entered the Gray Line Motor Tours bus to go to the eighty-passenger SS American Farmer, departing from Hoboken, New Jersey. A motorcycle police escort accompanied them to the pier, where the 18th Infantry Band played “appropriate music” for two hours. A pilgrim who had traveled with Party L in 1930 presented poppies to each woman, courtesy of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. At 3:00 p.m., the United States Lines held a farewell ceremony led by its president, Paul W. Chapman.

Colonel Pope, a city alderman, the captain of the American Farmer, and Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, the highest-ranking black officer in the U.S. Army, attended the ceremony. Emma Parker, of Virginia; Annie F. Bailor, of New Jersey; and Amanda Mitchell, of Washington, D. C., represented the pilgrims.

At least one other Virginia, Mary C. Harpole, of Phoebus, was in the group. “It is believed that the absence of any adverse of criticism or unfavorable propaganda is in a great measure due to the activities of Colonel Davis previous to his arrival in New York,” reported Pope. “This party gave absolutely no trouble and all appeared to be in a happy mood.” Davis accompanied the women on their journey across the sea.

Party E’s arrival in Paris was no less celebrated. The widows and mothers received “a rousing welcome when they arrived at the Invalides station” from Cherbourg, reported the New York Times. Colonel Richard T. Ellis, the officer in charge, met the women, who were treated to a performance of “Onward Christian Soldiers” by the noted black bandleader, Noble Sissle. The following day, the mothers, widows, and representatives of the African American colony in Paris heard an address by none other than Pershing himself, who “praised the Negro soldier with feeling and said that he was the equal of any fighting man in the world, if properly trained and properly led,” reported the New York Times. Despite the segregation, Emma Parker received the same care, attention, and respect during her pilgrimage as did the white Virginians.

After her journey to France, Mary Harris, who had sailed with Party K in 1930, submitted her final piece of correspondence to the quartermaster corps. The army had supplied a small card for the purpose, pre-printed with the words: “I beg to inform you that I have returned to my home safely and in good health. Sincerely, _______.” Harris crossed out “and in good health” and substituted the phrase “but ill from exhaustion.” However, she wrote, “Thank you for the privilege of going to my beloved son’s grave.” Grace Hicks added a personal note at the end of her note: “and with a thousand thanks.”

How many Virginians actually visited the European graves of their loved ones through the government-sponsored pilgrimages is unclear. Approximately 6,693 women from all over the country took the opportunity. The War Department initially determined that 226 women from Virginia were eligible to travel to Europe, of whom sixty-six indicated they would like to go in 1930 or a later date. Some women, like Helen Conrad and Sarah Inman, said they wished to go but ultimately did not travel under the government program. Others, like Emma Parker, were excluded from the original War Department report as their sons and husbands had died at sea. Many women never could have afforded such a trip otherwise. The unprecedented and incredibly generous offer was a shining moment for the U. S. Congress, the U. S. Army Quartermaster Corps, the grateful citizens of the country—and, above all, for the widows and mothers, who had given their husbands and sons to World War I.

-Mary Sine Clark, Acquisitions & Access Management Director

One Comment