On 17 April 1868, exactly seven years after a Virginia convention had voted to secede from the United States, another Virginia convention voted to approve a new constitution. For the first time in Virginia’s history, African American men participated in framing the state’s governing principles and laws.

The Library of Virginia’s Dictionary of Virginia Biography has recently completed a project to document the lives of these African American members of the convention, and their biographies are published online with our digital partner, Encyclopedia Virginia. These biographies (and many others) can be accessed through the Dictionary of Virginia Biography Search page or through Encyclopedia Virginia.

In 1867 Congress had required states of the former Confederacy (except Tennessee) to write new constitutions before their senators and representatives could take their seats in Congress.

On 22 October 1867, African American men voted for the first time in Virginia. In the election conducted by U.S. Army officers, voters answered two questions: whether to hold a convention to write a new constitution, and, if the convention referendum passed, who would represent them. Army officers recorded votes of white and black men separately, and some or all localities required voters to place their ballots in separate ballot boxes. Many white Virginians refused to participate in the election or were ineligible because they were former Confederates who had not taken an oath of allegiance to the United States. In racially polarized voting, the referendum passed and African American voters elected reformers to a majority of seats to the convention.

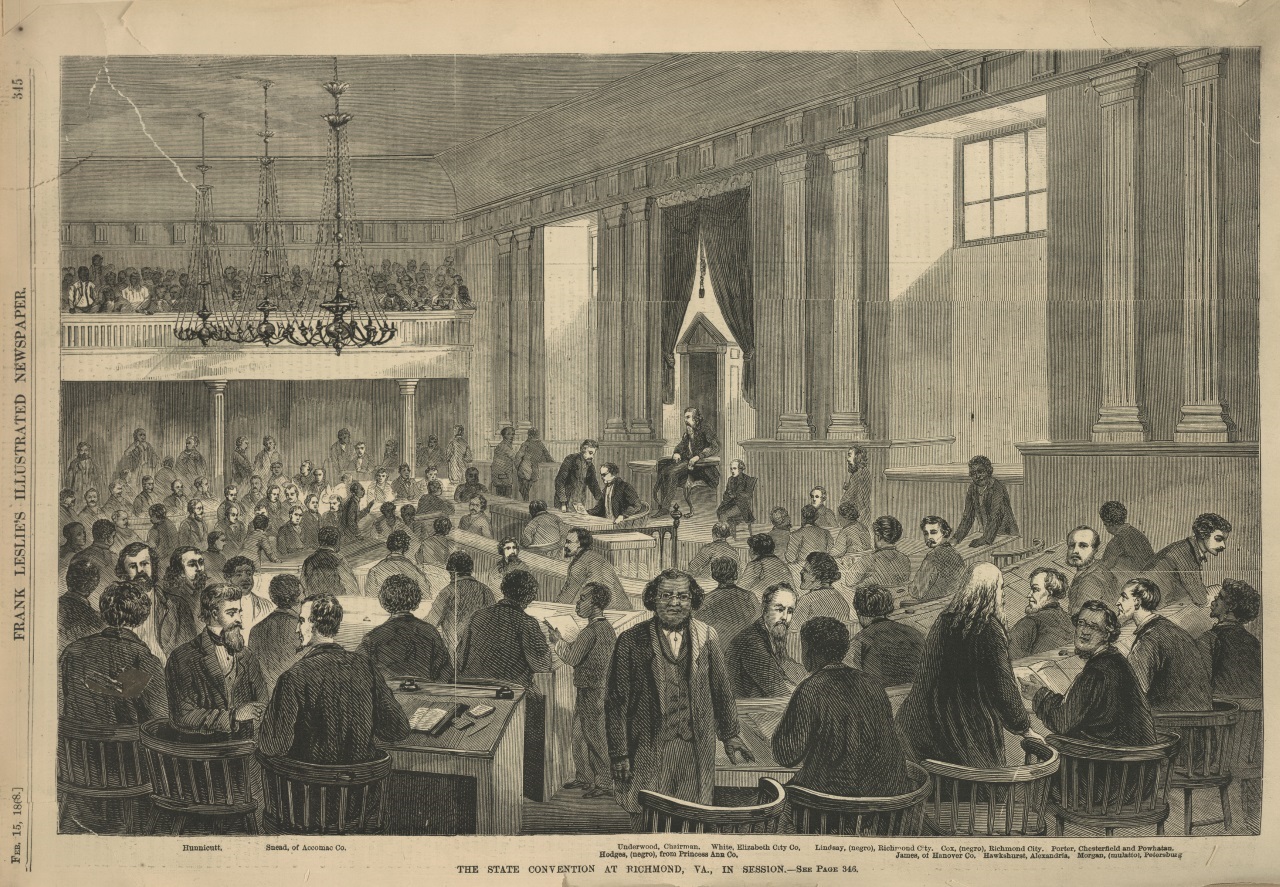

When the convention opened on 3 December 1867, at the State Capitol in Richmond, 24 of the 105 delegates were African Americans. They were the first black officeholders in Virginia’s history. Some had been free before the Civil War, while others had become free as a consequence of the war. Some could read and write, while others were illiterate. One member, James Thomas Sammons Taylor, served with the United States Colored Troops during the war. At the time of the convention, their wide-ranging occupations included skilled craftsmen, farmers, ministers, and teachers, as well as a dentist, grocer, newspaper editor, and musician.

The delegates were the objects of much abuse from hostile white politicians and newspaper editors who condemned the convention and its members. The Richmond Daily Enquirer and Examiner of 13 December 1867 referred to the delegates as “vile rabble.” Even officials such as Brigadier General John M. Schofield, the military commander in Virginia, described the African American members in disparaging terms. At best, he described John Watson, of Mecklenburg County, as “illiterate but intelligent and something of an orator. Honest.” Most of the time, however, his descriptions were more dismissive, such as his description of John Brown of Southampton County, as being a “slave until emancipated by the war. Illiterate. Esteemed honest, but is ignorant, and has no force of character.” However, these men were able advocates for the rights of freed people. Thomas Bayne, who had escaped from slavery in Norfolk and become a dentist, was a forceful proponent for African American suffrage

and for public education. James William D. Bland, who was born free in Prince Edward County after his father purchased his mother out of slavery, called for amending the preamble to the constitution by replacing “men” with “mankind, irrespective of race or color.

The constitution produced by the so-called Underwood Convention, named after its president, Radical Republican federal judge John C. Underwood, is also sometimes known as the Underwood Constitution. The constitution had significant differences from the state’s previous constitutions. It reformed local government on the more democratic model of the New England township, with most local officials elected by voters. It also required the General Assembly to create a statewide system of free public schools for all children for the first time. Although Thomas Bayne tried to persuade the other delegates to require that the public schools be racially integrated, his proposal failed.

The constitution’s bill of rights contained new articles stating that Virginia was part of the United States and that all attempts to dissolve the Union should be resisted; that the constitution and laws of the United States were the supreme law of the land; outlawing slavery with the words similar to those in the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; and declaring that “all citizens of the State are hereby declared to possess equal civil and political rights and public privileges.” The constitution also incorporated an 1866 act that allowed all Virginians born to at least one enslaved parent to inherit property from their fathers, in effect legitimizing births of persons whose parents could not legally marry before the Civil War. Voters ratified the constitution on 6 July 1869, but rejected clauses that disfranchised some former Confederates and barred them from public office.

Two members of the convention were part of free African American families who fought for racial equality before and after the Civil War. Willis A. Hodges of Princess Anne County (later the city of Virginia Beach) was among the most outspoken African Americans at the convention. Founder of an antislavery newspaper in New York, he befriended fellow abolitionist John Brown. Newspaper reports often referred to him as Specs or Old Specs because of his eyeglasses. An illustration in the nationally circulated Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper featured Hodges prominently. One of his brothers and a nephew later served in the House of Delegates, while another brother held local office and was an outspoken advocate for civil rights. Daniel M. Norton, who represented York and James City Counties, had escaped slavery and studied medicine in New York. He later served several stints in the state senate while his older brothers both served in the House of Delegates.

The convention was only the start of a political career for eleven members who went on to serve in the House of Delegates or the Senate of Virginia. Frank Moss, from Buckingham County, was the only African American to serve in all three bodies. A free man prior to the Civil War, Moss described himself as a “working man” and favored land ownership as a means for freedpeople to prosper. An antagonistic white man soon dubbed him “Francis Forty-Acre-And-A-Mule Moss.” Facing hostility and a spurious arrest for “using in public speeches, language calculated to produce breach of the Peace, and also cause alienation and discord between White and Colored Citizens,” Moss still won election to the Senate of Virginia in 1869 and to the House of Delegates in 1873.

The Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868 began a period of significant involvement of African Americans in the lawmaking process in Virginia, highlighted by their influential role in the creation of the Readjuster Party a decade later. Although they would suffer reversals of voting and civil rights by the turn of the century at the hands of the conservative Democratic Party, African Americans who participated in Virginia’s constitutional convention only two years after emancipation left a profound legacy for generations to come.

–John Deal and Mari Julienne, editors, Dictionary of Virginia Biography

One Comment