Seventy-five years ago today, Allied forces landed on the Normandy beaches of France, launching the invasion that would push the Nazis out of France and eventually end the Second World War in Europe. This year’s commemoration may be the last to include a significant number of veterans, most of whom are now in their mid-90s. With that somber reality in mind, the Virginia World War I and World War II Profiles of Honor Mobile Tour set out to gather stories of Virginia’s men and women who helped win the Second World War. They include several who, on that historic day in June, “embarked upon the Great Crusade [to] bring about the destruction of the German war machine.”

William T. O'Neill (1920-2019)

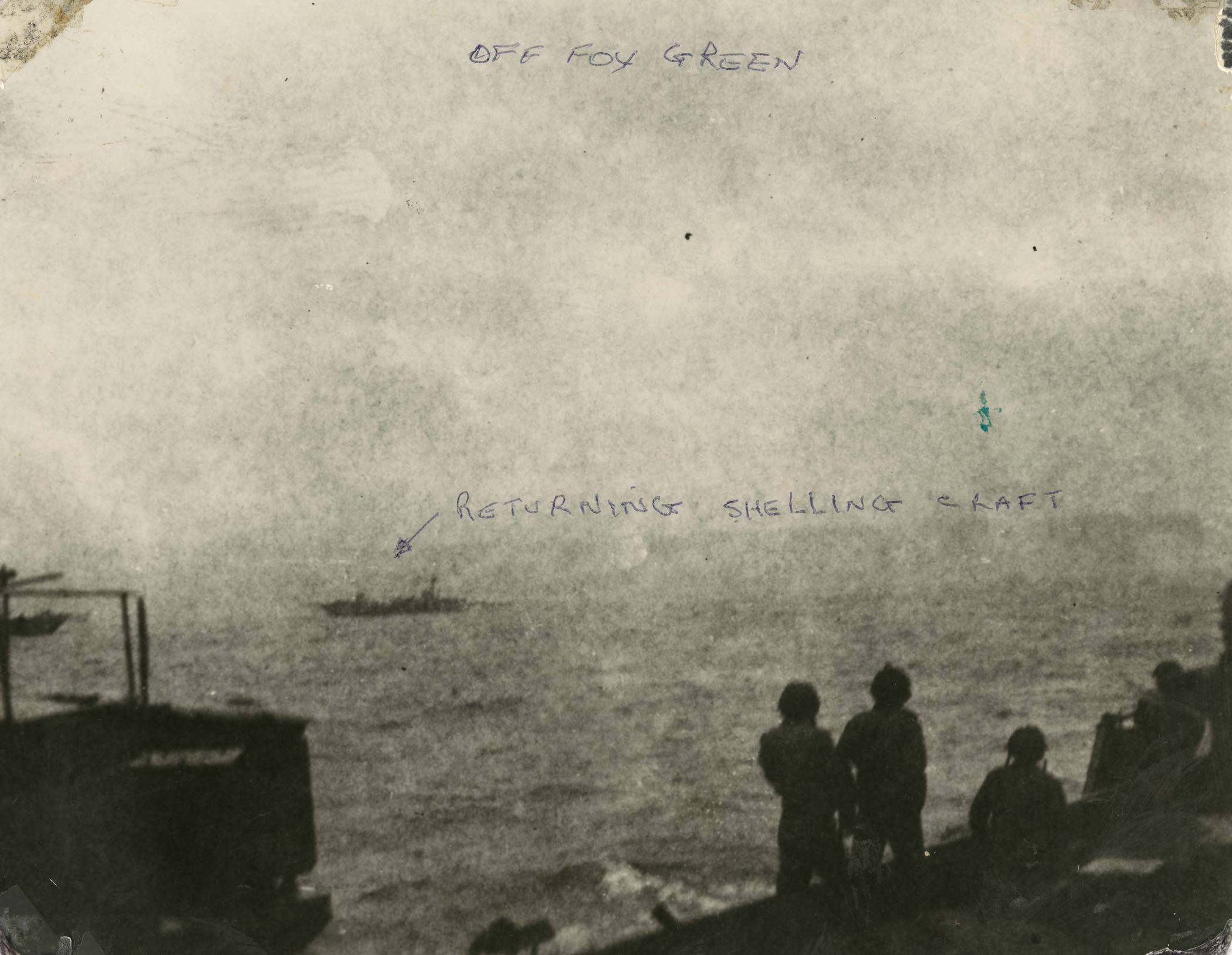

William T. O’Neill, for example, served on the U.S. LCT (6) 544, one of more than 4,000 landing crafts that were part of the massive invasion fleet. The craft was designed to transport tanks and other cargo; on D-Day, the 544’s specific mission was to deliver a Headquarters 1st Infantry scout team and a squad of the 5th Battalion Special Combat Engineers to a beach called Fox Green. They continued to land personnel throughout the day, as well as bringing the wounded off the beaches. O’Neill also witnessed, and photographed, the sinking of the USS Susan B. Anthony.

Major Thomas Dry Howie (1908-1944)

Major Thomas Dry Howie, who taught at Staunton Military Academy prior to the war, served as the operations officer the 3rd Battalion, 116th Regiment—known as the Stonewall Brigade—on D-Day; he was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions. He took command of his battalion on 13 July. On 16 July, he led his men in a night attack against German forces outside St. Lo to relieve an almost totally cut off 2nd Battalion. Howie instructed his men to use only bayonets and grenades, and they succeeded in relieving 2nd Battalion. He died on 17 July during a German mortar attack before he could lead his men into the city. His men took his body into the city on the hood of a jeep, so that he could be the first into the city, and placed it on the ruins of a cathedral, draped in an American flag. The story and photographs of the flag-covered body moved American readers. His name was not reported due to wartime restrictions, and war correspondents dubbed him “the Major of St. Lo.” Howie would later become one of the inspiration for Tom Hanks’s Captain Miller character in Saving Private Ryan.

During the weeks between D-Day and his death, Howie wrote frequently to his wife, Elizabeth Payne Howie, whom he called Bonnie. He sent them via V mail, or Victory mail, a method of communicating with soldiers stationed abroad which involved copying the letters to microfilm and then printing them back to paper upon arrival, a system which reduced the costs of transporting letters overseas. In his final letter home, dated 10 July 1944, Howie told Bonnie that although specific regiments couldn’t be mentioned in the news, “all the stuff you read in the papers about the heavy fighting & the 29th, particularly initially is about us. I’ll explain why some lovely, leisurely day.”

Other items from the Profiles of Honor collection include the citation for the Bronze Star Medal earned by Harold J. Davis for his actions on D-Day; photographs taken by Elwood Franklin Harrison, Sr., at Omaha Beach in 1945 showing wrecked ships and aircraft that remained from D-Day; and a newspaper clipping regarding the awarding of the Bronze Star to O. T. Grimes. There is also a photograph, letter, and citation from the Daughtry brothers. The three brothers, Joseph, John, and Richard Daughtry, all served in World War II. Joseph and John were both present on D-Day, and John died near St. Lo a few weeks later in a friendly fire incident.

The Virginia Military Dead Database lists 171 names as having died on 6/6/1944 at Normandy, France. A previous blog post explored the story of the “Bedford Boys,” who came from the same small town in Virginia and lost 19 of the 30 soldiers participating in the invasion. This was proportionally the most severe loss suffered by an American community on D-Day, and led Congress to eventually establish the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford.

Further items from Profiles of Honor can be found in the Library of Virginia’s online collections.

-Claire Radcliffe, State records archivist