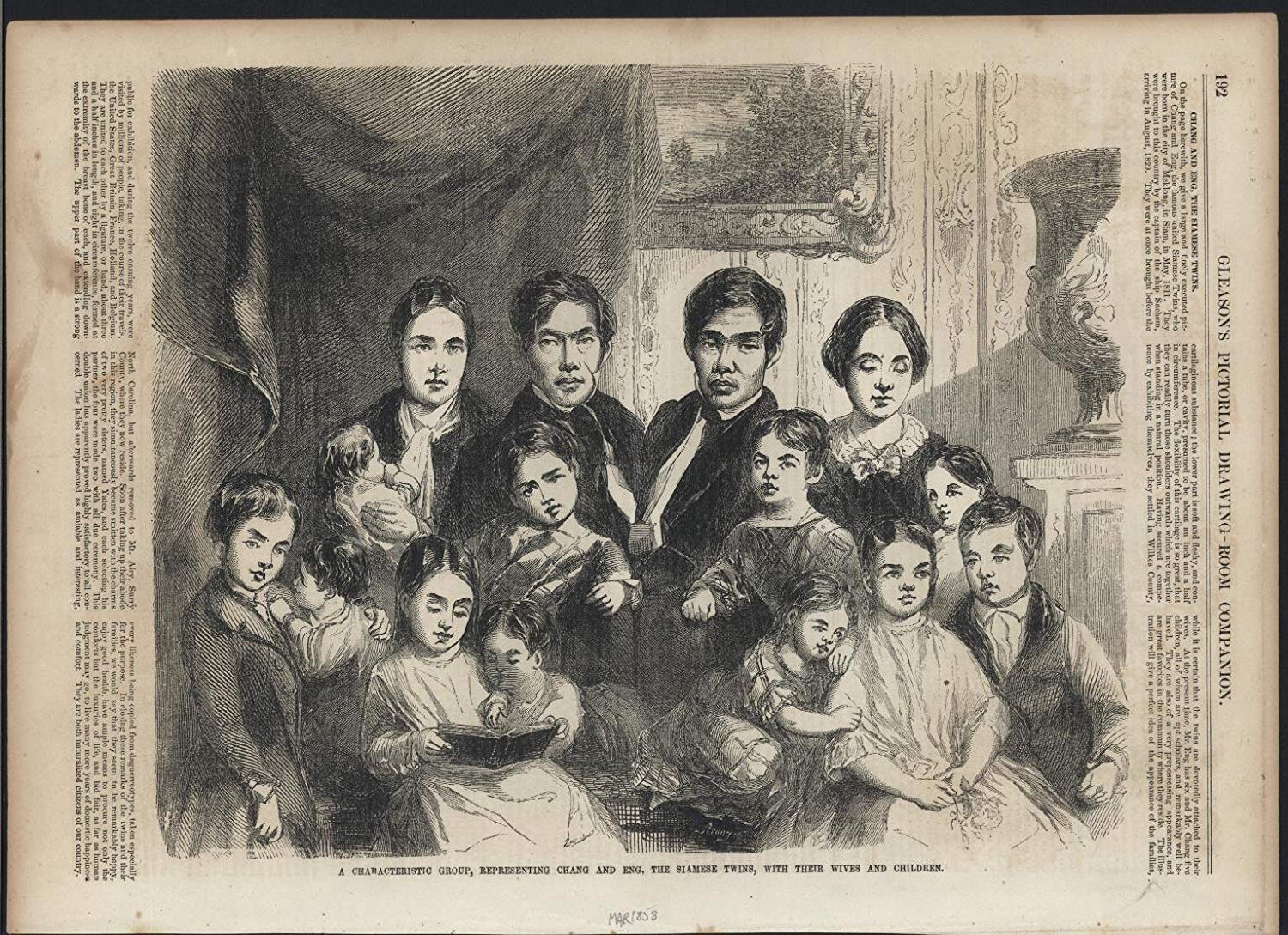

One of the more unusual stories found within the Library of Virginia’s collections involves the celebrated conjoined twin brothers Chang and Eng. Better known as the “Siamese twins,” they arrived in the United States from their native country of Siam (now Thailand) in August 1829. Joined together at the sternum from birth, they toured both the United States and Europe capitalizing on their physical abnormality. By exhibiting themselves at a local hotel, they enticed the public to pay twenty-five cents admission to watch the brothers demonstrate their dexterity in normal life skills. The Norfolk Herald reported in 1832, “They are lively and playful, speak our language with great ease…they are remarkably agile, can walk or run with great swiftness, and can swim as well as most single persons…in washing, dressing, or in any other occupation, they require no assistance.” Throughout their travels, the brothers were welcomed and successfully promoted as a curiosity to great numbers of astonished visitors. But during their brief stay in Virginia, they soon found themselves in violation of the Commonwealth’s tax laws.

Starting on 3 March 1832, great excitement was generated in Fredericksburg when The Virginia Herald announced the brothers’ arrival and subsequent exhibition in the Farmers Hotel. Located in the heart of downtown, on the corner of Caroline and Hanover Streets, this was considered the town’s leading hotel. Chang and Eng were ready to perform for the crowds of visitors willing to pay admission to see “the extraordinary manner in which they are joined together as one body.” Unexpectedly, however, either they or their manager Charles Harris, was approached concerning their failure to pay the state mandated $30 show license. For more than a decade, this licensing fee was required of “every exhibitor of a show” and unfortunately for the twins it was payable within every individual locality. It was one of many revenue producing ideas assimilated as “An Act imposing taxes for the support of government” which was renewed annually by the General Assembly. By March 1832 there were 113 counties, cities, and boroughs in the Commonwealth. The payment of such a prohibitive tax greatly limited the number and size of the communities the brothers could visit and interfered with their ability to earn a living. So they decided to ask the legislature for an exemption.

The First Amendment guaranteed the right of free speech and the right to petition the government to solve a problem or complaint. During the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War, petitions to the General Assembly were often the most direct way to highlight local issues to the legislators. The Library’s collection of nearly 25,000 petitions reveals how Virginians communicated their concerns on a wide range of topics, including: taxation, roads and canals, county divisions, divorce, emancipation of slaves, religious freedom, and military claims. Although not Virginia citizens, the brothers believed they should also be able to petition the legislature to reduce the financial burden this tax placed upon their livelihood.

On 12 March 1832, the “Memorial of Chang & Eng known as the Siamese Twin Brothers” was delivered to the House of Delegates and referred to the Committee of Finance for consideration. The petition began by explaining their arrival in the United States and favorable reception while touring Virginia and other states. During their travels they were generally not expected to pay either state or local taxes. Given the large amount of the required payment they considered it to be a “Prohibitory Tax” intended as a deterrent in “suppressing the exhibitions of Jugglers, Sleight-of-hand men and others who might corrupt the public morals of the Community.” This type of open air event tended to be rowdy. Surely, the brothers contended, the spirit of the law did not apply to their more refined style of entertainment. No public corruption would be experienced by those who visited the twins in a hotel. Finally, they emphasized that the “enforcement of this tax will prevent them from Visiting any Part of the State except a few large Cities and Towns.” The twins made their appeal and waited eagerly for the committee recommendation.

Regrettably, no record survives outlining the closed door discussions of the committee, although the logic of Chang and Eng’s appeal seems to have made sense to its members, who wrote “Reasonable” on the petition’s endorsement page. However, any change to the law required a floor vote by the House of Delegates, and the majority of delegates disagreed

This news was reported by the Richmond Enquirer on 17 March 1832: “A report of the Committee of Finance was received, upon the memorial of Chang and Eng, ‘known as the Siamese Twin Brothers,’ praying that they may be exempt from the tax to which exhibitors of shows are subjected. The committee reported favorably; but after some little discussion, the House rejected the resolution.” Disappointed, the brothers apparently accepted this decision, paid the tax, and revised their tour schedule, only appearing in Norfolk later that same month. Ultimately, life on the road became tiresome. The twins adopted the surname of Bunker and settled in Surry County, near Mount Airy, North Carolina, where many of their descendants live today. Both brothers died on the same day in January 1874.

-Tom Crew, Senior Reference Archivist