From 1795 to 1952, the United States’ naturalization process required a declaration of intention followed by a petition for naturalization. On 9 May 1918, Congress passed Public Law 144, An Act To amend the naturalization laws and to repeal certain sections of the Revised Statutes of the United States and other laws relating to naturalization, and for other purposes. Under the new law,

“any alien serving in the military or naval service of the United States during the time this country is engaged in the present war may file his petition for naturalization without making the preliminary declaration of intention and without proof of the required five years’ residence within the United States.”

The petitions used for these military naturalizations were the same form used for federal naturalizations beginning in 1906, and contains information on the petitioner’s birth, residence, occupation, military unit, immigration, spouse, and children, as well as the date of naturalization. Masculine pronouns were printed on the form, perhaps because there were very few naturalization records for women prior to 1922 since women automatically gained citizenship through their husbands.

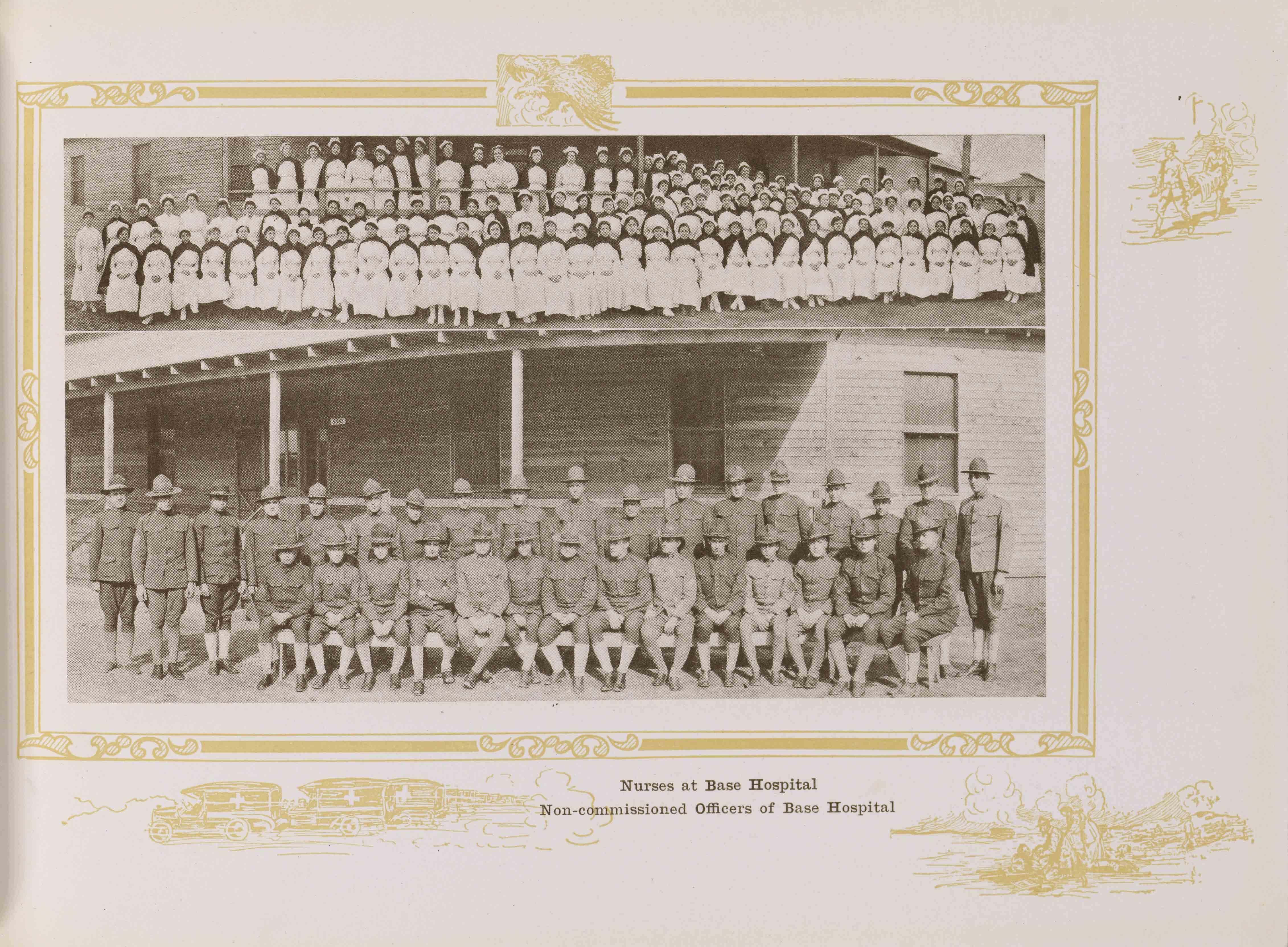

The expedited naturalizations took place on U.S. military bases around the world, including Camp (now Fort) Lee in Prince George County, which naturalized at least 6,834 soldiers and 21 nurses between 19 May 1918 and the armistice of 11 November 1918. Three courts handled the Camp Lee naturalizations: Prince George County Circuit Court, the Petersburg Corporation Court, and the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The Prince George and Petersburg naturalization records and microfilmed copies of the U.S. District Court records are housed at the Library of Virginia.

The naturalization of soldiers was described in a previous blog post. The 21 members of the United States Army Nurse Corps who were stationed at Camp Lee who chose to become U.S. citizens—all of whom were naturalized by Judge Jesse F. West of Prince George County on 20 September or 25 October 1918—had a somewhat different experience than their male counterparts.

In 1916, U.S. Army nurses had to be between the ages of 25 and 35. Those who were not U.S. citizens had to submit a declaration of intention prior to their appointment and complete the naturalization process as soon as possible. However, in the following year the requirement was changed to allow those who were between the ages of 21 and 45 who were citizens of allied countries to become nurses. Consequently, none of the nurses who served at Camp Lee had to become citizens in order to serve.

Nevertheless, most of the women who sought citizenship were naturalized soon after joining the military, with an average interval of just over 85 days—although Mary Irvine of Canada waited just 23 days, and Margaret Teresa McGreal of Ireland waited 268 days. The naturalization process could begin on the day of induction. For those who were naturalized on 20 September, Lt. Col. W. R. Dear of the Medical Corps and Capt. H. N. Dean of the Sanitary Corps signed affidavits stating that “the said petitioner is a person of good moral character, attached to the principles of the Constitution of the United States, and that the petitioner is in every way qualified, in his opinion, to be admitted a citizen of the United States.” For those who were naturalized on 25 October, the affidavits were signed on 10 October by chaplains Aubrey A. Stanley and Robert F. Tallmadge.

The Camp Lee naturalization ceremonies were increasingly grand public spectacles. The first ceremony on 19 May 1918 was held at the Petersburg courthouse for 150 soldiers and included an address and music by a regimental band. The largest ceremony, for 2,000 soldiers, was held on 16 August in Petersburg’s Central Park. The ceremony included music, the anthems of all Allied nations, demonstrations by militia units, and multiple addresses, including one in Italian.

The 20 September ceremony to naturalize more than a thousand military personnel was held at Camp Lee’s Liberty Theater. Fifteen women were naturalized, including Chief Nurse Catharine Helen Allison of Canada. They believed at the time that they were the first women to be naturalized under the May law, but women at Fort Riley in Kansas were in fact naturalized as early as 30 August. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that “Clad in their Red Cross nurse’s uniform of white with blue capes lined with red, the attractive cap, with a tiny red cross, the women offered an inspiring spectacle. Some in their early twenties, others more advanced in age, but all giving their services for the cause that the land of their adoption has espoused, spoke well for the part that woman is taking in the present struggle.”

Another naturalization ceremony followed on 25 October, the last ceremony for Camp Lee that was held before the armistice. In contrast to the previous ceremony, only 236 people were naturalized, including 6 women. The newspapers did not cover this event in detail.

Unlike the soldiers who were, on average, just over 26 when they became citizens, the nurses’ ages at the time of naturalization ranged from 23 (Margaret Henrietta McManus of Scotland) to 47 (Johanna Flynn of Ireland), with an average age of just under 30.

Nineteen of the nurses were British (8 from Canada, 7 from Ireland, and 2 each from England and Scotland). The other 2 were from Sweden. This was a major difference from the soldiers, just over half of whom were from Italy.

The nurses’ ages of arrival in the U.S. ranged from 5 (Clara DesJardins of Canada) to 29 (Mary Ethel Siple of Canada). The average age of just under 18 is comparable to that of the soldiers. The nurses’ arrival years ranged from 1885 (Johanna Flynn of Ireland) to 1915 (Mary Ethel Siple of Canada), with an average arrival year of 1908, which was approximately one year earlier than the soldiers tended to arrive.

Unlike the soldiers, the nurses resided in a variety of states. The soldiers were members of the 80th Division from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia; and the 37th Division from West Virginia and Ohio. Seventeen of the 21 nurses listed addresses in the United States: six from Massachusetts; three from New York; two each from Connecticut and Illinois, and one each from Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The remaining four were from Canada, with two each from Nova Scotia and Ontario.

The naturalization records of the 21 nurses who chose to become United States citizens during their assignment to Camp Lee have some distinct differences from the soldiers who were naturalized at the same camp in terms of age of naturalization and places of origin and residence. Women were also among the last to be naturalized, waiting 4 or 5 months after the passage of the military naturalization law. These records show that despite the masculine language and lack of reference to the U.S. Army Medical Department, female nurses sought citizenship in return for their military service just as their male counterparts did.

To learn more about the immigrant experience in Virginia, check out the Library’s exhibit New Virginians: 1619-2019 & Beyond, through 7 December 2019. To learn more about World War I nurses in Virginia check out the blog post “Our Share In The War Is No Small One”: Virginia Women And World War I.

Cara Griggs, Reference Archivist