This fall, a local records archivist at the Library of Virginia collaborated with a U.S. History teacher at Matoaca High School in Chesterfield County to present a hands-on workshop to his students using local records as primary sources. The school librarian coordinated the logistics of using the library space during this two-day adventure, with all five of the teacher’s classes participating, totaling 120 students, for 90-minute sessions each.

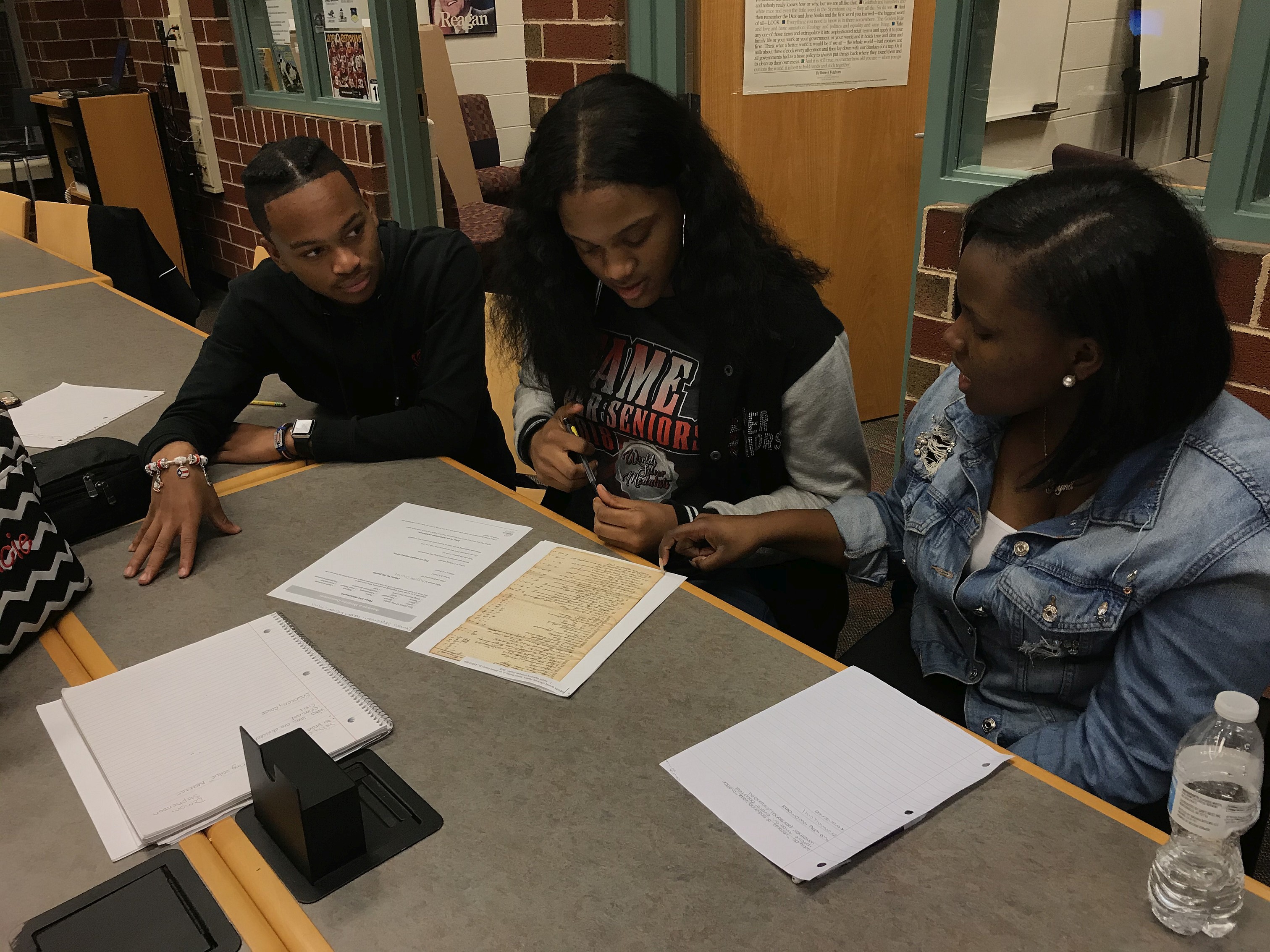

Class discussion of a page from a 1790s-era county minute book

The students were introduced to electronic resources at LVA that they could access from home, such as Virginia Chronicle, LVA’s historical archive of Virginia newspapers, and Making History: Transcribe, LVA’s crowdsourcing website for transcribing a variety of digitized historical documents. They also received a brief introduction to Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, which is an ongoing project digitizing pre-1865 documents from a variety of record collections at LVA relating to the African American experience in Virginia.

After this overview, and an introduction to courts and court records, students broke into pairs or small groups to analyze facsimiles of primary source documents from courthouses around the commonwealth, using document analysis sheets from the National Archives as a guide. Documents included plats, petitions, coroner’s inquisitions, estate inventories, genealogy charts, marriage licenses, and pages from minute books or order books.

After about 20 minutes of analyzing their assigned documents in small groups, they came back together as a class and the archivist projected the image of each document so each group that worked with a particular document could explain what it was, why it was created, how it was used, and what small “mystery” or research question it might have presented them. That way, everyone had the opportunity to see and discuss each of the different documents. After collecting the document analysis sheets and the facsimiles, a new set of documents was distributed and students analyzed them as well, this time solely through discussion.

- High school students across the academic spectrum have difficulty reading cursive handwriting, regardless of its neatness. This generation was not taught penmanship, so it may as well be a foreign language.

- Spatial reasoning with letters/words/phonetics is a challenge. Because students did not learn penmanship, and according to the teacher, many students also did not learn phonetics when learning to read, trying to “decipher” either a handwritten or typed document is challenging for them. For example, people in their 40s or 50s may have learned that if a letter in a word is unrecognizable or out of context, they might look to another word that has a similar letter shape in it, sound out the word, and then understand the mystery letter in the mystery word. However, a current high school student may have difficulty doing this.

- How students approach problem solving has much to do with their confidence in themselves and with finding the problem relevant to them. With teenagers, it very much is “all about Me,” so the challenge for the teacher (and in this case, the archivist) was finding ways to associate the historic documents with something relevant in their lives.

Overall, the opportunity for an archivist to interact with students in their own school and to introduce them to the concept of what an archives is and to have them work with primary source materials from local court records was a great way to celebrate archives!

-Tracy Harter, Sr. Local Records Consulting Archivist

One Comment