This is a post in our new series highlighting the people and programs of the public libraries of Virginia. To view more posts about our Commonwealth’s great libraries visit our Public Libraries category. New content will appear on the second Monday of the month.

This is a post in our new series highlighting the people and programs of the public libraries of Virginia. To view more posts about our Commonwealth’s great libraries visit our Public Libraries category. New content will appear on the second Monday of the month.

In 2012, the Library of Virginia began a partnership with the public libraries of the Commonwealth to digitize historical material in their possession, and by 2015 the Virginia Yearbook Digitization Project had come into being. Learn more about the beginnings of the project here and see some wonderful cover art examples here.

According to the Encyclopedia Virginia: “Virginia’s public schools had been segregated racially since their inception in 1870…Through local organization and the ballot, black Virginians were able to pressure state and local authorities to provide support for their schools. Following the disfranchisement of black voters in the Virginia Constitution of 1902, however, funding for black schools fell far short of what white schools received, and the discrepancies in salaries for teachers and administrators were stark.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court deemed school segregation unconstitutional in the decision of Brown v. Board of Education, but the practice did not end in Virginia. Instead, white politicians kicked off a period of so-called Massive Resistance, during which some Virginia counties went so far as to close public education completely rather than desegregate their schools. While these events may seem long past in the eyes of younger generations, their legacies are with us every day.

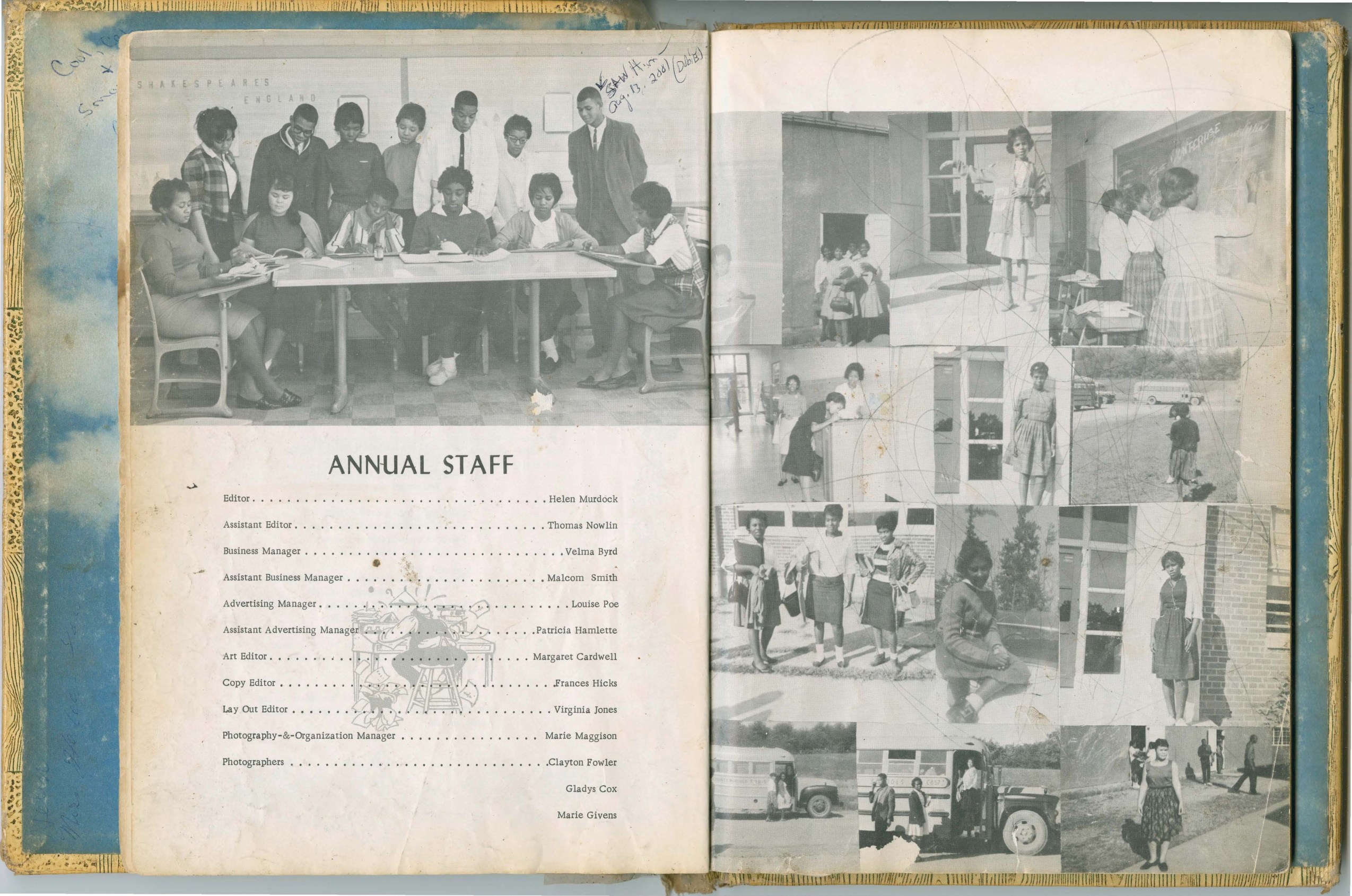

One such legacy, which might seem trivial at first glance, is the lack of African American school yearbooks in our Yearbook Digitization Project. Although this is not a life or death situation, it is emblematic of a larger failing on the part of the (mostly white) government entities at the state and local levels that decided what history was worthy of preserving. Virginia had roughly 100 years of segregated schooling, but the vast majority of our yearbook collections from those years contain only the faces of white schoolchildren.

There are many reasons for this, but they mostly stem from a common root of discrimination. Since African American schools were vastly underfunded compared to their white counterparts, some did not have the resources to publish yearbooks to begin with, or at least to publish ones that have stood the test of time. Our digital yearbook collection has been compiled in partnership with public libraries all over the Commonwealth who have preserved the yearbooks of the communities they serve. However, during that period in question, Virginia public libraries were also segregated and so did not collect the yearbooks created by African American schools.

Those yearbooks that do still exist are largely in private hands. We have been honored to have organizations such as the Luther H. Foster Alumni Association, working with the Nottoway County Public Library System, allow us to digitize their yearbook holdings. Members lent their yearbooks to the local library, where they were packaged and shipped at the Library of Virginia’s expense to a professional digitization lab. They were then uploaded onto the Internet Archive, where they can be seen by anyone with an internet connection and searched for specific names, making them more accessible not only for those people whose memories are preserved in the pages but for the larger public.

Although school segregation was immoral, many students still experienced joyful times and cherish their memories. High school will always be a formative experience in an American teenager’s life.

Luther H. Foster Alumni Etta Booker Neal, a member of the Alumni Association recently wrote:

As I have said many times, I am thankful to have attended Luther H. Foster. Being from Prince Edward County when schools closed in 1957 [because of Massive Resistance], I was taught in churches for a year to keep learning math, to read and write. I lost one year out of school, then in 1959 I moved to Burkeville with my big sister and between her and my brother who transported me weekly for 5 years from Rice to Burkeville in order to finish high school, Luther H. Foster, from the eighth grade to my senior year.

I am not only thankful for myself but there were others from Prince Edward County who had relatives to live with in order to attend school. However when P[rince] E[dward] schools reopened in 1964 [after Massive Resistance ended] I just had one year left to graduate and decided to finish at Foster.

So yes I appreciate my family who helped me as well as afforded the opportunity to attend Foster.

The Library of Virginia and public libraries across the Commonwealth cannot turn back time to undo the injustices committed by school segregation, but this partnership allows us to take a small step forward to address some of the wrongs of the past.

Sadly, recent circumstances have forced us to hit the pause button on scanning new yearbooks for a time. However, if you possess yearbooks missing from our collection, specifically those from African American public high schools, and you would be willing to loan them for scanning through your local public library, please contact Jessi Bennett, the coordinator of the Virginia Yearbook Digitization Project, at jessica.bennett@lva.virginia.gov.

The current online holdings of African American public high school yearbooks include:

- Campbell County High School, The Wildcat, 1962-1964

- Central Augusta High School, Cavalier, 1962, 1964

- Essex County High School, The Tiger, 1955-1956, 1960-1961, 1963, 1965-1966

- George Washington Carver High School, Trojan, 1963 and 1966

- George Washington Carver Regional High School, The Hawk, 1949-1967

- Jefferson High School, The Jeffersonian, 1954-1955

- Luther H. Foster High School, The Bulldog, 1958-1965, 1970

- Luther Jackson High School, The Tiger, 1955-1965

- Luther P. Jackson High School, The Cougars, 1957

- Northampton County High School, The Lighthouse, 1950-1970

- Peabody High School, The Peabodian, 1963-1965

- Richmond County High School, The Viking, 1969-1970; The Golden Crest, 1965; Excelsior, 1959, Memories, 1957

- Thomas Hunter School, The Seahawks, 1969

- Watson High School, The Watsonian, 1953, 1958, 1963

You can access the entire Virginia Yearbook Digital Collection online here.

–Jessi Bennett, Digital Collections Specialist