“DANGER! WOMAN’S SUFFRAGE THE VANGUARD OF SOCIALISM” blared a broadside published around 1913 by the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage. It warned women that “If you hold your marriage, your family life, your home, your religion, as sacred, dear and inviolate” then they should fight against extending the franchise.

How could women oppose equal voting rights? The Library of Virginia is commemorating the anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment with an exhibition, We Demand: Women’s Suffrage in Virginia, that highlights the fight to achieve the franchise. But as we honor the extraordinary efforts of suffragists, let’s pause to consider those women who fought—perhaps incomprehensibly—against it.

Formed in 1912 to counter the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, by December 1913 the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (sometimes styled Virginia Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage) reported about 1,900 members throughout the state and opened a headquarters in Richmond. The organization articulated its views largely through correspondence and the innovative strategy of distributing free literature through bookstores. On one occasion, in May 1913, it sent Maria Blair, a Richmond educator and civic leader, out to Tazewell County to speak against suffrage.

Anti-suffragists, or antis, claimed that the majority of women did not want the responsibility of voting, which they deemed a privilege rather than a right. While both groups emphasized the importance of women in the domestic sphere, they viewed the effects of voting in opposite ways. While suffragists such as Lila Meade Valentine insisted that the franchise was essential for properly raising children, the VAOWS maintained that women were too elevated in society to delve into the dirty business of politics, arguing that “Women cannot have the franchise without going into politics and the political woman will be a menace to society, to the home and to the state.” Along these same lines of separate gender roles, a VAOWS pamphlet, Why Women Should Oppose Equal Suffrage, asserted that:

The Framers of the Constitution gave the ballot to men because they had the strength to enforce the laws they made.

Woman has no right to vote on questions which concern offices which she cannot fill. She has no right to vote to send men to war when she cannot stand beside them to take the risk of wounds or death.

God did not create woman to be a soldier, a sailor, a civil engineer, a juryman, a magistrate or a policeman. He founded her relations in nature’s law when he made her mother of men.

The antis stressed these traditional gender roles in novel ways. In a pamphlet titled Household Hints, the New York-based National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) supplied tips to “housewives” on handling daily tasks, such as “clean dirty wall paper with fresh bread” and “grass stains may be removed from linen with alcohol.” But the pamphlet also dispensed such advice as “control of the temper makes a happier home than control of elections” and “common sense and common salt applications stop hemorrhage quicker than ballots.” The pamphlet implored voting against woman suffrage:

BECAUSE 90% of the women either do not want it, or do not care.

BECAUSE it means competition of women with men instead of co-operation.

BECAUSE 80% of the women eligible to vote are married and can only double or annul their husbands’ votes…

BECAUSE in some States more voting women than voting men will place the Government under petticoat rule.

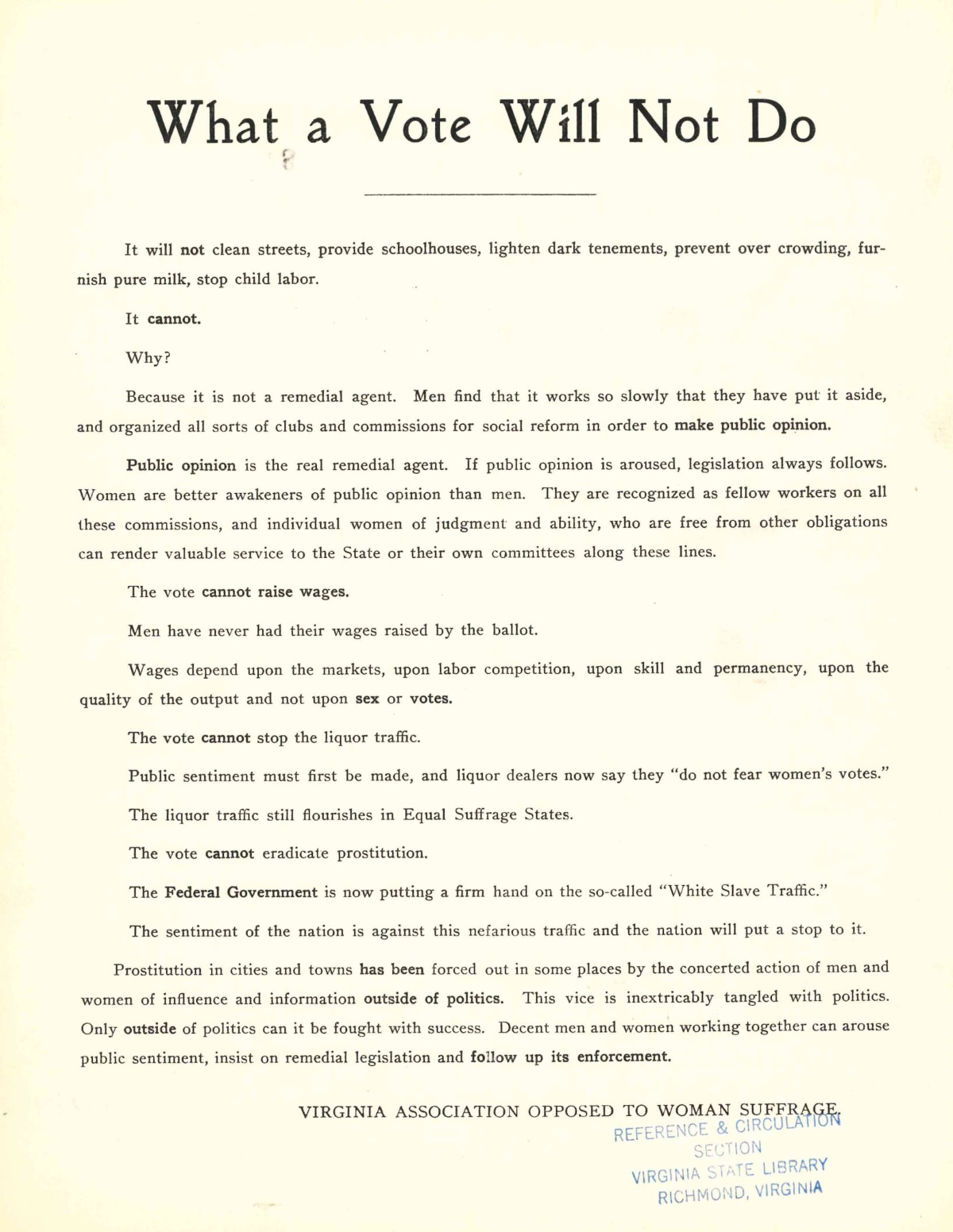

Anti-suffragists even claimed that women could not undertake their domestic duties as well as exercise the franchise. The New York state association argued, “Our women do not seem to have any superabundance of strength and nerves anyway, and what will they become if the woman suffrage reign should come in? … The homes, the babies, the charities, the schools need woman, and let our legislators consider carefully whether woman can attend to all these duties and a hundred others, as well as do their part in the political world.” In an apparent appeal to those seeking relief from society’s ills, the VAOWS argued that granting women the right to vote would not stop child labor, curb the liquor traffic, keep the streets clean, or build schools.

Anti-suffrage literature often contained racial, ethnic, and class prejudices. The VAOWS warned that equal suffrage was fraught “with especial danger to our dear Southland. If the ignorant vote is to be doubled, the vicious vote increased, and a highly undesirable and probably purchasable vote added to that allowed under present electorate, the good women of Virginia cannot lend all their strength to help the men in their struggle with existing conditions, but must use it in a similar struggle with the vote of their own sex.” Making an even stronger statement, VAOWS literature warned that twenty-nine Virginia counties would go under “negro rule” if women were given the vote.

Who were these women fighting against equal suffrage? Like their counterparts, antis were predominantly urban elites, but they were less likely to be involved in Progressive era causes, such as public health and civic improvements. That did not mean, however, that they refused to accept women in the public sphere. Jane Meade Rutherfoord, the first president of the VAOWS, had also been a founder and president of the Woman’s Club of Richmond (like suffragist Mary-Cooke Branch Munford), the city’s preeminent literary society that included many suffragists among its ranks. She supported expanding employment opportunities for women, but only if the women were the “bread-winners” in their household.

Many VAOWS leaders, like Rutherfoord and her successor as president, Mary Mason Anderson Williams, were active in heritage and preservation organizations. Williams argued that a federal amendment would deprive states of the right to govern their own affairs and insisted that allowing African American women the franchise could destroy social order. Well-known novelist Molly Elliot Seawell published The Ladies’ Battle (1911), which outlined the perceived ills that befell women in equal suffrage states, such as higher rates of illiteracy, poverty, divorce, and violence. Views of this sort spurred one suffragist to quip in the Richmond Evening Journal from July 1916, “I think that all one needs to be converted to the cause is to hear an anti-suffragist argue.”

After enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920, Williams wrote an appeal in the Richmond Times-Dispatch for white anti-suffragists to register and vote. “In view of the fact that colored women are registering in large numbers,” she warned, “the women of Virginia who have consistently opposed woman suffrage, and who still oppose it . . . feel it their duty to register and to be prepared to exercise their influence for the best interests of all our people, both white and colored, and to oppose any radical or dangerous changes which may be proposed by agitators.”

Of sixteen leaders in the VAOWS who could be identified, only five registered to vote in the autumn of 1920. One of those was Catherine Coles Valentine, a member of the executive board and wife of famed Richmond sculptor Edward V. Valentine. And while vice president Margaret Wilmer did not register to vote, her twenty-two-year-old daughter Elise did! Despite her pleadings, Mary Mason Anderson Williams herself did not see fit to register until January 1921.

-John Deal, Editor

We Demand: Women’s Suffrage in Virginia is the Library of Virginia’s exhibition commemorating the centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, and is scheduled to be on view at the Library through December 5, 2020. (NOTE: the Library is temporarily closed to the public to help contain the spread of COVID-19. Please check the main website for updates on the closure status.)

The Library’s accompanying book, The Campaign for Woman Suffrage, is available for purchase from The Virginia Shop.

A traveling exhibition will be on view at local libraries and historical societies around the state. See the schedule here. (NOTE: This schedule is also subject to change due to the COVID-19 response. Please check with the contact listed on the traveling exhibition page for further information.)

This exhibition is a project of the Task Force to Commemorate the Centennial Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote.

5 Comments