During the antebellum period in Virginia, enslaved men and women who gained their freedom did have the potential to enter into their own business and entrepreneurial pursuits. Many free Black people were able to take skills and trades developed during years of forced labor and turn them into some form of self-sustaining industry. It was an extremely difficult process, and only a small percentage (who were themselves barely 11% of the African American population by the time of the Civil War) operated and maintained some form of business or enterprise.

Establishing a business or a reputation as a tradesman was no easy feat. The process was exceedingly convoluted, with nothing guaranteed for freemen. By law freemen were not allowed to remain in the state unless they successfully petitioned the General Assembly for permission to remain in the state following their emancipation. Without this permission, freed Black men and women risked being expelled to other states, losing connection with their still enslaved families. In the case of tradesmen, they also risked losing established clientele, and the loss of revenue would prevent them from earning enough to eventually purchase the freedom of family members.

Many of these petitions follow similar lines. A large collection of the citizenry for a town or county would praise the character of the petitioner and attest to their usefulness and skill in their craft. Looking at some of these petitions highlights the extent to which communities would go to provide reasonable depictions of petitioners. One remark on the petition of Peter Strange, a blacksmith, commented that, “I have considered him a faithful, humble, well behaved man, without any fault known to me… I have no doubt with should he be permitted to remain in the Commonwealth, the policy if the law in that behalf so far from being infringed will rather be enforced by shewing that a man in his condition by exemplary demeanor may gain the knowable distinction of being permitted to remain, and thus holding out the strongest inducement to good conduct.” Such language was common in favorable petitions, reflecting how formerly enslaved people made a mark in their communities from a business perspective. It also demonstrates that freed Black men and women were looked at more favorably if they were able to provide a service to the community that directly benefited the white population. In the petition of one Robin Brown, another blacksmith, one commenter noted that, “The steady and proper pursuit of his trade, will render him useful to the community.”

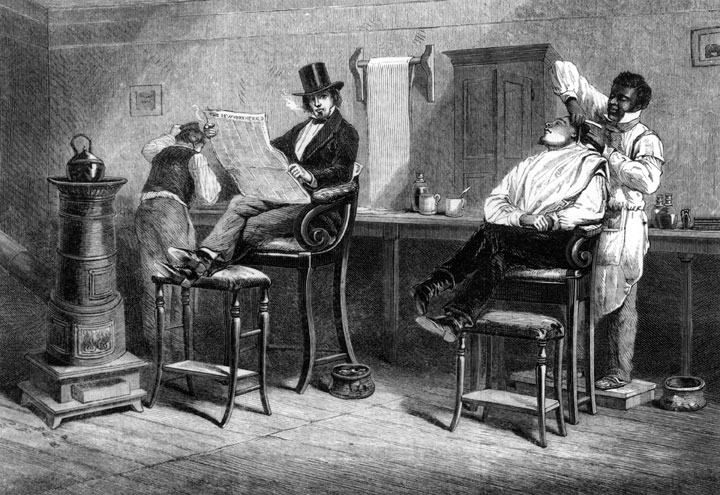

Some of the entrepreneurial enterprises freedmen frequently pursued, such as running barbershops, brought them into contact with primarily white patron bases. As such, these clients were more willing to write favorably on the petitions of freedmen who wanted to remain in each county or town. The petition of Frederick Williams of Lynchburg, a barber, had over eighty signatures praising his character and value to the community. Another petition for Daniel Warner, a barber in Fauquier, attested, “From the general good character of the said petitioner the undersigned take pleasure in aiding him in the prosecution of his object and although they consider that applications of this character ought to be granted with great caution yet in this instance they feel assured that no possible injury would result to the public, should his petition be granted.” Freed blacks who could create a relationship with the white population of an area were more favored, as seen in this type of petition, and creating such relations helped navigate the fragile atmosphere of their new freedom.

Free Black women also petitioned to remain in Virginia to maintain their own business or trade pursuits. A petition for Fortune Thomas, a baker in Halifax, remarked, “The humble petition of Fortune Thomas a free Woman of color of the County of Halifax most respectfully therewith, that about 20 years ago she settled at Halifax Court House as a baker… And that has been constantly assured by the ladies that they can in no manner dispense with her services and assistance & that no party or wedding will begiven, without great inconvenience should her shop and cake bakery be broken up and discontinued.” Another appeal, for Harriet Cook of Leesburg remarked, “It would be a serious inconvenience to a number of the citizens of Leesburg to be deprived of her services as a washerwoman and in other capacities in which, in consequence of her gentility, trust-worthiness, and skill she is exceedingly useful.”

Successful Black entrepreneurs were always at risk of upsetting a community’s white population, and even small grievances could spell disaster. Apart from social threats or threats to property, the legal system codified these risks. Since freed Black individuals were not legally allowed to remain in the state, even strenuous petitions to make an exception for a person based on their usefulness to the community could fail. In these instances, individuals were forced to leave the state or face massive fines along with other repercussions. Even if they were allowed to remain, their families were not necessarily given the same privilege; in case of Wilson Morris, his approval to remain in the state was granted, but his wife and children were made to leave.

The years leading into the Civil War provided some former enslaved people with the opportunity to pursue their own businesses and entrepreneurial endeavors. While the circumstances surrounding these were complicated and there was a volatile legal process by which freedmen and women could even attempt these pursuits, some did find their way to successful livelihoods during this period. Using the skills they had been forced to learn under slavery, some were able to eke out a respectable life for themselves, and in some cases their families.

-Robert Hines, Stacks Technician

Further Reading

- “The Roots of Enterprise: Black-Owned Businesses in Virginia, 1830-1880.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 100, no. 4 (1992): 515-42. by Loren Schweninger

- Boss: The Black Experience in Business, PBS Documentary

-

The History of Black Business in America : Capitalism, race, entrepreneurship

by Juliet E. K. Walker