Every year, as the air turns cold and memories of Thanksgiving turkey fade away, children begin the age-old tradition of penning a letter to Santa Claus. During the Richmond Christmas season of 1900, the large dry goods firm of Julius Meyers & Sons—whose slogan was “Everything for Everyone!”–held a contest for the best letter to Santa. The grand prize? A real live donkey!

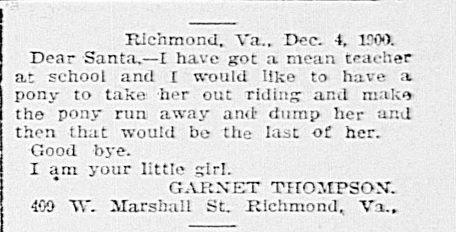

What kid wouldn’t write their most saccharine, ingratiating prose to the Big Man to win an actual donkey? Well, that’s precisely what the winner, six-and-a half-year old John Sullivan, did to win the contest. However, this post is not interested in young Master Sullivan’s obsequious note. No, another contestant caught our eye, Miss Garnett Thompson of 409 W. Marshall St., Jackson Ward, not far from Meyers & Sons’ huge building at Broad and Foushee Streets.

Garnett made no qualms about why she wanted to win the donkey from Meyers & Sons. She had “a mean teacher at school,” and she wanted to send her out on the aforementioned grand prize and have it “dump her and then that would be the last of her.” We’re pretty sure that put Miss Thompson on the naughty list, but we admire her moxie.

Garnett Douglas Thompson (1886-1975) was about 14 when she wrote that letter (teen angst?), and I decided to use some of the Library’s resources to put together a cursory biographical sketch to learn more about this plucky teen with the no-nonsense personality.1 She seems to have maintained the pluck and independence exhibited in her Santa letter for her entire life. Using the Library’s Ancestry subscription, I found the 1900 U.S. Census (also available on FamilySearch), which shows her living with her father, a merchant; mother, a homemaker; and two sisters, one older and one younger, at 409 W. Marshall St. The family was well-to-do enough to employ Etta Dandridge as a “domestic.”

Curious about which school Garnett might have attended, I looked up her address on the FIMo (Fire Insurance Maps Online) subscription database. After locating the home, which still stands, I searched adjacent map pages looking for a nearby school. Based on proximity, it is likely that Garnett attended Leigh Street School at the corner of Leigh and First Streets, which also still stands. The school building, now senior apartments, was partially condemned in 1909, with the third floor shut off. The white students were transferred to Richmond High School at 805 E. Marshall St., and the refurbished Leigh Street building was renamed Armstrong High School and designated as a segregated school for Black students. Around this time, Jackson Ward transitioned to a bustling African American neighborhood and business hub. When Armstrong High moved to a new address, the building became Booker T. Washington School.

Documents from the Virginia Department of Vital Statistics, available on Ancestry for Virginians, reveal that by 1907 Garnett had married Harry S. Snyder, a tinner. Just a few years earlier, at the age of 16, Harry was arrested for shooting his brother-in-law, Lorenzo Siebert Cease. Cease was alleged to have drunkenly accosted his wife, Harry’s sister, and trashed the family home in Highland Park. In retaliation, Harry was purported to have shot him through the window. Harry remained silent in the face of the charges, which were eventually dropped for lack of evidence.

The newly married couple, who according to newspapers had filed for a marriage license in Baltimore, lived with her parents and extended family at 409 Marshall St., according to the 1910 Census. According to city directories on Ancestry, Garnett was living in Norfolk when Harry shipped overseas with the 116th Infantry during World War I. Garnett is listed in the Veterans Affairs BIRLS (Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem) Death File. I initially assumed this was related to Harry’s war service. However, I should have known better given our formidable subject. Based on notations in the file for Garnett’s funeral in 1975, included in the L. T. Christian Funeral Home collection, she served as a Yeoman (F), also known as a Yeomanette, in the Naval Reserves during WWI. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., maintains some records relative to women in the Naval Reserves. I could not access those records at this time, but future research could yield additional details about Garnett’s service during the Great War.

Harry and Garnett divorced in 1920. The divorce record indicates three years of desertion as the cause for the split, putting the separation at 1917. Perhaps Garnett envisioned a troop transport ship like that prize donkey, a method to rid herself of another problematic person. The 1920 Census, available from Ancestry or FamilySearch, shows that Garnett worked as a clerk at the Norfolk naval base, a common transition for discharged Yeomanettes, and roomed at a boarding house in Norfolk’s Madison Ward with another female naval clerk.

Further searches of the Library’s Virginia Chronicle newspaper database brought to light numerous social announcements in the newspapers during Garnett’s early adulthood, noting travels from Richmond to a waterside cottage at Virginia Beach, Willoughby Spit, New York City, Miami Beach, and other locales. Once single again, Miss Thompson (she resumed use of that surname) often traveled with her sister, Clara, who was also unmarried. The pair ventured overseas in summer 1930 on the American Shipper and stayed at London’s Imperial Hotel. On the ship’s passenger list, they noted Garnett’s current occupation…teacher.

Eventually, the two sisters lived together at 1109 W. Grace St., and then later at the Gresham Court Apartments on W. Franklin St. A year after Clara died in 1958, Garnett made her own funeral arrangements with L. T. Christian Funeral Home. Since she had no surviving immediate family, she specified a fairly austere ceremony with a closed casket and interment beside Clara at Riverview Cemetery. She lived alone for another 16 years before passing away in 1975 at the age of 89.

That young lady who penned a very honest letter to Santa in 1900 seemed to live her life with the same self-possession and confidence expressed in that note. So, if you’re chatting with family by phone or Zoom over the holidays, and you learn of a spunky great-great-aunt or great-grandfather, try using some of the Library’s resources to learn more. If you’re not sure how or where to begin, our staff is ready to assist with resources and research strategy.

Hopefully Santa will bring us all a donkey, so we can put 2020 on it and send it off to “dump her and then that would be the last of her.”

Happy Holidays!

Footnotes

1For a list of available subscription databases, go to https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/using_collections.asp#_research, then select Databases & eBooks.