For Local Records staff at the Library of Virginia, one of the few positive effects of the current COVID-19 pandemic has been the ability to take on a variety of teleworking projects. Through these efforts, our small staff has managed to accomplish a great deal. At of the end of July 2020, seven archivists began to focus a great percentage of their time on completing both an in-house and teleworking chancery project.

Around this time, I completed my first teleworking project—adding surnames and names of enslaved people to chancery causes and compiling suits of interest. I was able to do this work remotely by utilizing previously processed and scanned chancery collections found on the Library of Virginia’s Chancery Records Index. These teleworking projects allow a more in-depth analysis of each cause. They also offer current staff a unique opportunity to study earlier projects and update them according to our current processing standards—using all the tools in our toolbox so to speak. In the process, I reviewed 392 causes (1831-1868). I added an additional 4,800 surnames and names of enslaved individuals, and compiled eight additional causes of interest.

Hanover County, along with 21 additional Virginia counties, experienced a catastrophic loss of many of its loose records and volumes. Despite the destruction of many county court records during the Civil War, the chancery records generated by the Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery and the Circuit Court remain intact. For this reason, these records are an unparalleled historical and genealogical resource. Some of the more interesting updated causes cover a variety of topics: free African Americans, extensive information on slavery and the enslaved, the construction and location of important businesses such as mills, military bounty land warrants, the construction of a public road, a prominent Virginia family, and a personal recollection of the effects of the Civil War.

In this particular county, numerous chancery causes contain detailed and specific information on enslaved individuals. Local men who sold people into slavery are identified along with times and locations where enslaved people were sold. Enslaved men and women are listed as property and sources of their labor are readily noted—including occupations and conditions. Through these documents, individual stories become apparent.

For example, in the case 1834-003 Exr of Mahala (free) v. Admr of John Bowe, etc., Mahala is revealed to be a “free woman of color” living in Hanover County, formerly enslaved by Colonel Thomas Tinsley. In 1824, John Bowe legally emancipated her along with another unnamed girl he had gained the legal right to enslave from a Mrs. Bowler. He planned to educate both women. Mahala, however, soon died. Hanover County officials probated her will in 1831. In it, we learn that Mahala had children who had not been freed with her, and that she had purchased the legal right to them from Colonel Thomas Tinsley.

The case 1838-005 Mary V. Cross, gdn v. Lucy T. Cross, etc., (pages 124-125) tells the story of an enslaved man named Ned, a highly skilled blacksmith and wheelwright who had died recently. Defendant Lucy Cross alleges that John J. Howell hired Ned from her, and let Ned keep the profits of his labor. In exchange, Ned reimbursed Howell for the cost of hiring him, and paid an additional fee. With some of the profits he accrued, Ned made an agreement with Samuel Sublett that provided for the eventual freedom of Ned’s wife, Rachel. As an enslaved man, Ned could not “own” Rachel himself, and so Sublett agreed to purchase the legal right to Rachel and to free her upon Ned’s death.

Cross argues that since Ned (now deceased) could not own property, his profits (and his blacksmithing and wheelwright tools) actually belong to her, and states that she wishes to give them to Rachel and to Ned’s son. She sought to retrieve them from Howell, who retained the shop materials and had advertised them for sale.

In the case 1842-016 Alexander W. Talley, etc. v. Exrs of William Y. Dejarnette, William Y. Dejarnette willed that within one year of his death, the enslaved woman Maria and her children were to be emancipated and transported to Ohio. Dejarnette directed his executors to purchase 100 acres of land adjacent to the county in which Quakers from the Cedar Creek settlement had removed. He expressly hoped that the family would be placed under the care of the Quakers.

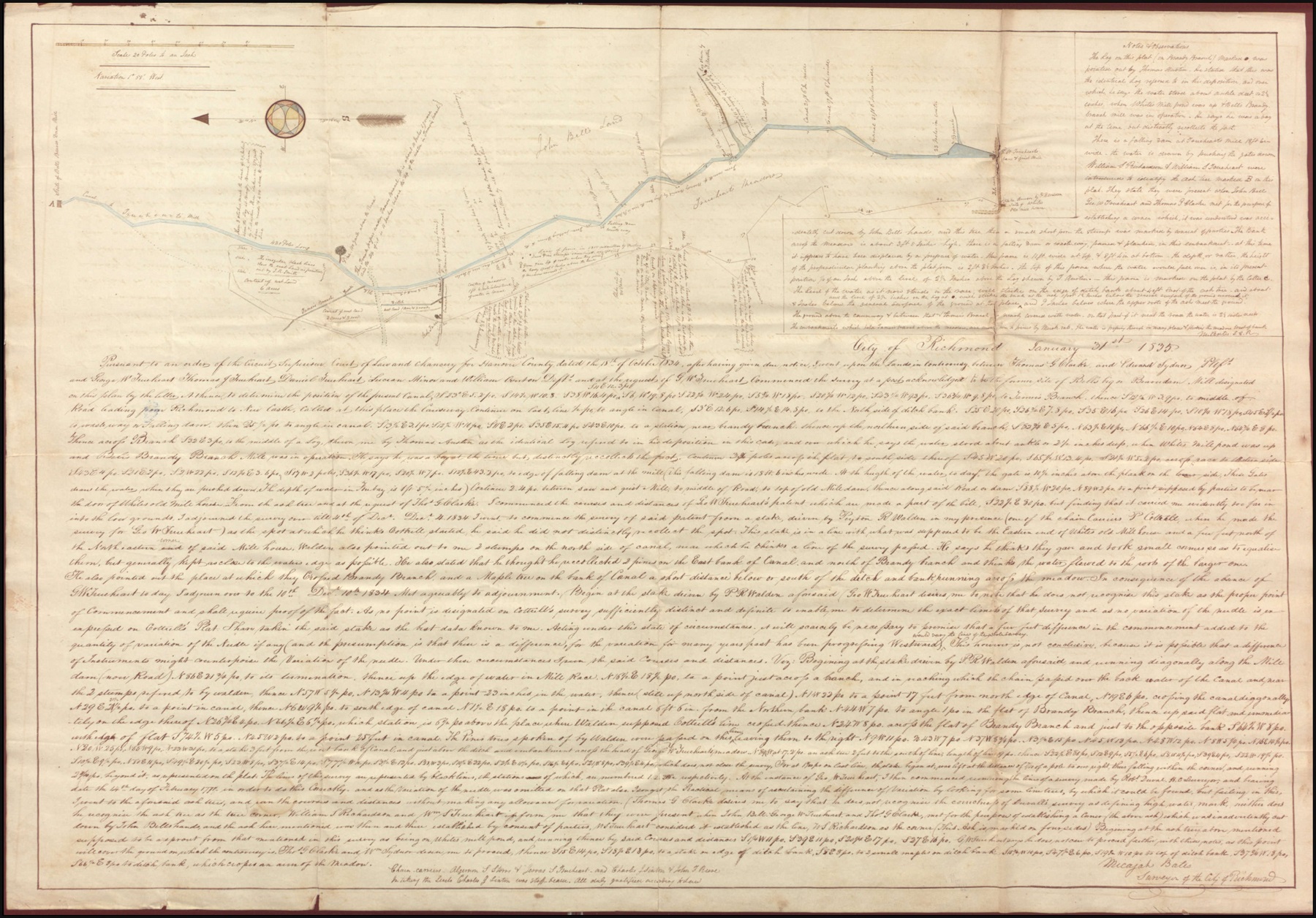

The case 1835-001 Thomas G. Clarke and Edward Sydnor v. George W. Trueheart, etc. explores the history of county mills. This cause involved a property called Whites Mill, formerly held by John Bell, and once held by William White and Dr. John Adams of Richmond. The defendant, George Trueheart, bought the mill, taking down the dam and moving the site of the mill to a different side of the pond. He conducted water to the mill by a canal and turned ground formerly covered by the pond into a meadow. Trueheart then obtained two land office treasury warrants—one for 50 acres of land and the other for 100 acres of land. He then constructed a new dam. This caused valuable meadowland to be lost under water and therefore the plaintiffs requested removal of the dam. An oversized plat included with the clause provides a detailed rendering of the property.

In 1866-004 Robert Ellett v. James W. Taylor, various mills and their proximity to each other are noted. The cause itself deals with the reestablishment of a grist mill. The plaintiff was a carpenter by trade. Mills mentioned include King’s Mill, Ellet’s (flour), Perrin’s, Edmund Winston’s, Crenshaw’s, Gilman’s (flour), Dr. Wooldridge’s, Thomas Stanley’s, Ryall’s, Wickham’s, Rocketts’ (flour), Morris’, Terrell’s, Carter’s, Taylor’s, Harris’ (flour), Mallory’s (flour.) John James operated a steam mill at Ashland. Haxhall or Haxall Mills operated in the City of Richmond.

There is a large collection of military bounty land warrants found in numerous collections of chancery causes throughout the Commonwealth. Cause 1839-003 Hester Ann Jones by, etc. v. Elisha Jones, infant, etc. is a new addition to the collection. In this cause, the federal government granted Bounty Land Warrant No. 6908 to the heirs of Ella Jones, an heir of Absalom Jones. Certain officers and soldiers of the Virginia Line, Navy, and Continental Army during the Revolutionary War received bounty land warrants. This particular warrant conferred 3,373 acres of land. For more information on this subject, check out the blog post “A Collection within a Collection: Bounty Land Warrants Found in Chancery Causes.”

The construction of a public road indicates the continued modernization of the county. In 1855-006 Albert S. Jones v. Lucy A. Ball, the cause involved the proposed construction of a new public road from Richmond to Hanover County. The new road would cross the tracks of the Virginia Central Railroad. The plaintiff, Albert Jones, claimed that he did not have the privilege of using the new road due to the defendant’s obstruction of an old road known as Meadow Bridge Road. In exchange for a change in the new Meadow Bridge Road, the county paid Jones to construct a short road on his own property, bringing him closer to Mechanicsville Turnpike and his own mill. Jones allowed the change in the new road because he believed that the old road would remain open. Lucy Ball, however, considered the old road a nuisance to her property and erected a fence across it. Jones’s servants proceeded to drive his cattle through a panel in the fence. The county officials made a case that the old road was part of a public county road and that Ball could not erect a fence.

The prominent Carter family of Virginia appears in 1861-029 William Fanning Wickham, gdn v. Robert Carter Wickham, etc. Lucy Carter, the daughter of Robert Hill Carter of Shirley Plantation, married Edmund Fanning Wickham. They owned a plantation of over 2,000 acres called South Wales. After both she and her husband died, their son Robert Carter Wickham, the cause’s principle defendant, also passed away. Commissioners then sold the plantation to Edmund Winston. The cause is of interest because the plaintiff owned 15 enslaved individuals that worked on the South Wales plantation, alongside many hires. Many of these individuals had surnames registered. The cause contains information on the occupations and selling of the various enslaved men and women.

The final cause, 1868-001 Thomas Parker Carver, infant, etc. v. Admx of Dr. Robert M. Carver, highlights the personal effects of the Civil War. In stark terms, Dr. Robert M. Carver is identified as an abuser and an adulterer. The cycle of abuse continued with his eldest son, the plaintiff, who abused his mother, the defendant. In a lengthy letter, the defendant discusses the Civil War and its effects on her family. Carver served in the Civil War and may have suffered from post-traumatic stress. The defendant, Fanny P. Carver, also had a younger son who was part of the City Reserves before his death.

Carver became a feme sole, which gave her greater legal and financial autonomy. The cause includes substantial information about the people she enslaved. It also notes that her brother had a contract with the federal government to procure shingles. A plat included with the cause may depict the Bellevue plantation.

The images of other surviving records from Hanover County appear on Virginia Memory as part of the Lost Records Localities Digital Collection. The finding aid for Hanover County chancery causes includes additional causes of interest. The initial processing and scanning of the Hanover County chancery causes, 1831-1913, were made possible through the innovative Circuit Court Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts.