On 13 September 1886, an ill W. W. Colley returned to Richmond, Virginia, from Liberia, trying once again to outrun scandal. However, the month-long boat trip across the Atlantic was too slow. When he arrived in Richmond, the Foreign Missionary Baptist Convention asked him to forfeit the post at the Bendoo Mission in Liberia he had held for the past three years. They had heard troubling rumors that he had murdered a man. Years earlier, while working for the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) as a missionary in the Yoruba area of Africa, Colley had been accused of sexual impropriety with a housekeeper, a charge he denied and felt was racially motivated. It had been just one more reason to leave the SBC and found his own Black-led mission board to Africa, but now that very board was also recalling him.

In January 1877, just about a decade after the end of the Civil War, James B. Simmons, corresponding secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS), headquartered in New York, sat down to write to Charles Corey, head of the ABHMS-funded Richmond Institute: “My Dear Bro. Corey I am delighted to see the letter of your old pupil W. W. Colley in today’s Herald… Tell him to bear the standard bravely! He is the first of Richmond Institute graduates who goes to Africa and the first from any of the seven schools!”1

Simmons was responsible for expressing the views of the ABHMS to the heads of schools that the organization started across the South shortly after the Civil War. The predominantly white Northern Baptist groups, along with their counterparts in other denominations, saw it as their mission to educate, evangelize, and prepare for Christian ministry those formerly enslaved Black men (and to a lesser extent women) in the South. However, their resources were stretched thin, often pitting them against one another for funds. In March Simmons wrote again, “Were I you, I would emphasize & emphasize & emphasize, the matter of giving intelligence about Africa, – & praying for Africa, and working for Africa! The school that does the most for that cause will be most loved & helped by our people, and at the same time will be not a whit less useful in raising up able & useful laborers for the home field.”2

Richmond Theological Institute, the precursor of Virginia Union University, was founded in 1865 and became alma mater to a great number of Virginia’s “first generation of freedom,” especially pastors. These new pastors saw it as their duty to go out and spread the message of their faith even further. Black Virginian missionaries to Africa were not new—in 1821, Reverend Lott Carey, who was born enslaved in Charles City County in 1780 and had purchased a right to his own life in 1813, and famously traveled to Liberia as a missionary. It was in his hallowed footsteps that many hoped to follow, including a student named William Washington Colley.

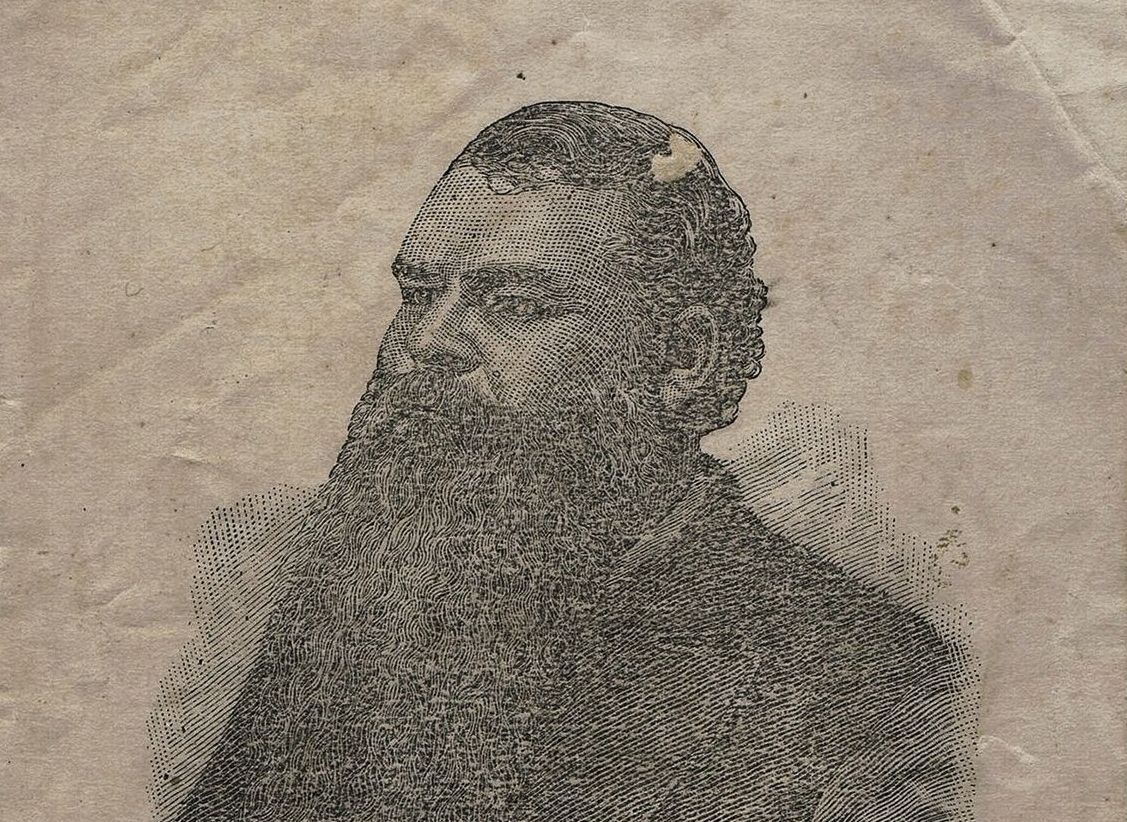

William Washington Colley (better known in the historical record as W. W. Colley) is thought to have been born enslaved in Virginia around 1847 (some sources say as late as 1854). Little is known about his young life; rumors after his death claimed that his father was white and his mother Native American. However, he lived and was seen as a Black man, and is first seen in the historical record shortly after the end of the Civil War. He entered Richmond Theological Institute as a student in 1870, graduating in 1873. He credited the school with the creation of his “deep and powerful impressions which gave me the strongest missionary inclinations.” Whatever monetary machinations might have gone into the focus on missions at the school, Colley was sincere in his belief that he was called to evangelize.

He lost no time in pursuing those feelings. In 1875 Colley traveled to Africa as a missionary under the auspices of the Southern Baptist Convention. The Baptist denomination had first split in 1845, causing the creation of the Southern Baptist Convention when Northern Baptists refused to allow Southern enslavers to hold key positions. The Southern Baptist Convention still had some reservations at this point about employing Black missionaries, but general belief at the time held that Black men were better able to withstand the climate and sicknesses of the so-called “Dark Continent.”

Colley served for five years with white missionary William J. David in an area of modern-day Nigeria populated by the Yoruba people. Many missionaries (and settlers/colonizers in nearby Liberia) brought their American societal structures with them (unconsciously or not) and viewed themselves as superior to the native Africans. It must have been very difficult for Colley, a Black American, to be stuck in this created hierarchical structure between David, a white American who believed himself superior to Colley, and the Yoruba people, to whom both David and Colley felt superior.

Both David and Colley viewed those who were not Christian as “heathens” and strove to “civilize” them. David wrote to the Southern Baptist Convention that their mission near Abeokuta was a place “where scores of men and women are learning the way of life,” presumably the Western Christian way.3 However, David had a second layer of prejudice that he also could direct against Colley at times as he viewed him, as well as the Africans around them, as “sons and daughters of Ham,” a biblical reference that implied darker-skinned people were the cursed descendants of one of Noah’s sons.4 While David wrote to the SBC, urging them to send him white missionaries to work with, he also noted in his diary that he “had to use a club” on the workers constructing the mission’s buildings as they were not working fast enough. A few days later he had Colley supervise the workers instead and noted that he too resorted to flogging the men.5

The Southern Baptist Convention received more complaints about Colley than about David, perhaps they feared more virulent retribution for lodging complaints against David directly. “Is it right for a minister of God to be beating or horsewhipping any of his converts?” members of the community asked in a letter to the Richmond-headquartered Mission Board.6 The parishioners of the mission also complained when Colley fired Lewis Murray, a local Baptist minister who had been hired to work at the mission’s school. Those writing the Foreign Mission Board did not feel that Murray had done anything to warrant firing. They felt it was retaliation for an earlier conduct complaint that Murray had sent to the Board regarding the two single women living in Colley’s house. Mrs. Parmer and her adult daughter Sallie both worked for the mission and slept in bedrooms on opposite sides of Colley’s.

It is unclear if Colley knew these complaints came directly from members of the community but he staunchly denied any acts of impropriety, telling Richmond Institute head Charles Corey later that the rumors had been started out of “prejudice to me, as I did not do everything to suit Dr. T[upper, corresponding secretary of the SBC Foreign Mission Board] and friend D[avid].”7 He also complained that when David returned to the United States due to illness, his already-meager monetary support stopped coming altogether.

Ill, and with a floundering relationship with his employer, co-worker, and those he was supposed to be serving, Colley returned to the United States in 1879. The Southern Baptist Convention had found that their “work there [was] not prospering in his [Colley’s] hands” and they directed him “to return to this country with no view of his going back to Africa.”8 He told Solomon Cosby, a classmate who arrived a year earlier under the Foreign Mission Board of the Colored Baptists State Convention of Virginia, that the Southern Baptist Convention Board would not treat him “as a man nor a Christian.”

Having resigned from the SBC, but not resigned to leaving Africa behind completely, Colley sought a new way to mobilize Black missionaries. Perhaps he took note that Foreign Mission Board of the Colored Baptists State Convention of Virginia had not been able to set up a mission by themselves, forcing his former classmate Cosby to use SBC resources and facilities. Colley spent the next few months traveling around the South gathering support for a regional missionary convention. His Richmond Theological Institute community included pastors all over the South, and in 1880 the Baptist Foreign Mission Convention was founded in Richmond, presided over by many prominent professors and pastors in the area. The organization subsumed several smaller state organizations, making Solomon Cosby, still in Yoruba, its first missionary.

Of course cooperation was one thing, financial means were another. W. W. Colley was named the first corresponding secretary and traveling agent of the new organization, charged with traveling across several states to raise funds to send others to Africa. He saw Africa as the primary focus for Black missionaries, telling audiences that “this is their labor field.”10 While many newspaper reports proclaimed the interest in his talks, which were open to white and Black audiences alike, it seems it was probably the topic that was the draw, not the speaker. While advertisements to his talks promised tales of “snail soup and monkey stews,” singing in “the African language,” and “the Thunder god and thunder bolt covered with human blood offered by the sins of the wild people,” Colley was known “not [to be] endowed with any special gifts or eloquence” relying instead of his “power of appeal and knowledge of the field” to solicit donations.11

That prodigious knowledge may not have been enough. The Convention was paying Colley $1,000 to raise funds, but his first report showed that he only raised $506.78 while incurring $225.06 in expenses.12 The same thing occurred the second year, with Colley unable to raise enough money to justify his own salary. The following year the position was given to someone else.

But there was a different position ready for Colley. As he had been canvassing for funds to pay missionary Solomon Cosby’s salary, Cosby, “stricken with fever, and at times seemingly forgotten,” had died.13 The newly formed convention needed missionaries.

On 8 December 1883, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that on 1 December “Rev W. W. Colley and Rev J. H. Pressley [sic], and their wives” had embarked on the Monrovia “intending to labor among the Vey tribe within and beyond Liberia.” The paper failed to mention the two single young men accompanying them, John J. Coles (sometimes written Cole) and Hence McKenny (sometimes written McKinney), who were to study at Liberia College first and then join them in the mission field. It also failed to mention the names of their wives, an all too common fate. Georgie Carter Colley was born on 25 October 1858 and grew up in Portsmouth, Virginia. She taught school in Norfolk and Nansemond counties, marrying W. W. Colley on 1 November 1883, just a month before they left for Liberia. Lest the marriage seem hasty, one profile written at the time assured readers that “the subject of this sketch [Georgie Colley] had been duly consulted on the question of becoming a wife and a missionary.”14 One wonders if Colley hoped a wife would squelch any rumors of impropriety this time around. We do not know much about Georgie and William’s relationship, though they had several children, two while in Africa. Likewise we do not know what Georgie did day to day, though keeping house and helping in the school was probably enough to fill her time. It was noted that “she enjoyed her work among the heathens and they were devoted to her.”15

Although the name of J. H. Presley’s wife, Harriette Estelle Harris Presley, was also missing from the clip, in time it would overshadow his own. Joseph and Harriette, called Hattie, met at Richmond Theological Institute where they were both students. Hattie was one of a very small number of women that were allowed to attend the school before the completion of the women’s college, Hartshorn Memorial. They were said to have been “fond friends, and this friendship bloomed into love for each other.”16 While many accounts of her life praised her beauty and Christian character, Hattie must have also been ambitious to pursue a degree at a predominantly male school in the late 1800s. They were married in June 1883, arriving in Liberia, like the Colleys, as newlyweds.

Liberia, with its history of American immigration, seemed a logical choice for American missionaries to base their operations. Some moved there permanently, while others, like the Foreign Baptist Convention, came temporarily. The issue of Liberian colonization, in many ways, dovetailed nicely with goals of American missionaries who were looking to “better” the lives of the native peoples of the region. As one Annual Report of the Colonization Society stated, “The only man available for the great work of opening Africa to commerce and civilization is the Negro of America. He can lie here, for it is the habit of his race, and being fully civilized and Christian too, he is the Agent, and the only Agent that the world contains adapted to this purpose [emphasis in original].”17

The journey from Virginia to Liberia took a month, so by the time the couples (along with Coles and McKenney) arrived they were already exhausted. The new convention had decided to settle in among the Vey peoples near Cape Mount. In 1884 they established the Bendoo (Bendu) Mission on the banks of Lake Peisne (Piso), which consisted of a simple wooden house for the missionaries “and a few huts for their native servants…situated on the most attractive spot along the lake.”18

It was a personal victory in a year full of trials. In August 1884, Charles Corey received letters from his former students Colley and Coles. Colley wrote that they all had been taken with “climatic fever and have continued to suffer” most especially Joseph Presley who had become “deranged”. Colley noted that Presley “does not and has not known me for nearly two months. He knows me by a new name and as his ‘best friend’.”19

Coles, who had found Liberia College lacking for his purposes and had joined Colley to help while Presley was sick, wrote two days after Colley on 6 August 1884, adding that sometimes Presley did not even know Hattie, his wife. Both men mentioned that Georgie Colley gave birth to a daughter in early August, but that Hattie and Joseph Presley had lost a baby girl in June. Before month’s end Hattie Presley had died as well.

Hattie became the Foreign Baptist Convention’s first “martyr,” and they praised her seven months of service on the mission field and lamented what might have been. Joseph’s health never fully recovered; once he was well enough to travel he returned to Virginia. Lingering effects of his illness continued to plague him all his life and he was forced to beg the Convention for some sort of pension since he was unable to do much work. His health deteriorated to the point that towards the end of his life his second wife had to place a notice in the Richmond Planet warning people that “he is not capable of entering into or forming contracts.”20

The Colleys worked on with Coles and McKenney. In 1885, Coles set up a secondary mission post called Jundoo Mission on the opposite side of Lake Peisne (Piso) and McKenney opened Marfa Station. There was hope of setting up an industrial school at the Bendoo mission but once again lack of funds intervened. Coles returned to the United States hoping to raise more support for the mission, taking with him a small boy. He returned to Liberia in early 1887 alongside two Mississippi couples and his new wife, Lucy Ann Henry Coles, although no mention is made of the child.

Lucy Coles took immediately to the work and the couple stayed at the mission until 1894, when monetary issues finally came to a head and the mission buildings had to be sold for scrap to pay debts. John J. Coles would die shortly after returning to the United States but Lucy spent many years working for the Foreign Baptist Mission Convention and giving talks about Africa.

Colley (and presumably his wife Georgie and two children) were not there when Coles returned. Once again Colley had his work upended by scandal. In 1886, according to Colley’s account, a mentally ill man entered the mission house. When the man did not leave as requested, Colley shot his gun as a warning, purposefully not aiming at the man. However, in missing the man he hit a small boy nearby. A Liberian court found Colley innocent of murder and/or manslaughter, and he was already planning to leave Liberia because of his health. However, rumors reached Richmond before he did, damaging both his and the mission board’s reputation. The Foreign Baptist Mission Convention asked that he not return to the mission after regaining his health. The mission did continue under the Coles for a bit, and later iterations rebuilt in the same area; but as one member of the convention said later, “Holding up to public gaze Rev. W. W. Colley’s mistake was the beginning of our decline of our mission work in the eighties.”21

Colley did not let this stop him from continuing to fundraise for and support African missions. It was his life’s work and he signed his letters, “Yours for Africa.” He continued his speaking engagements across the southeast and into the mid-Atlantic. He became editor of the Baptist Companion in Portsmouth, Virginia. However, trials seemed to follow him; the printing office burned in 1887 and in 1894 his house in Richmond burned. He estimated the loss, including “some valuable African collections,” at about $5,200. He only had insurance for about half that amount.22

The family, which by now included six children, moved around the area. The 1900 census found them in Rockingham County, Virginia, and they later moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. When he died in his early 60s in 1909, his youngest child was about eleven. Georgie Carter lived another 30 years, spending her last few in New York with one of her daughters. Despite being recalled home twice from his chosen foreign mission field, Colley continued to do the work he felt called to do and the profession on his death certificate read “missionary work.”

Footnotes

1 James Simmons to Charles Corey, January 26, 1877, Richmond Theological Institute Correspondence, Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

2 James Simmons to Charles Corey, March 12, 1877, Richmond Theological Institute Correspondence, Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

3 Tupper, H., 1880. Foreign Missions of the Southern Baptist Convention. Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, p. 432.

4 Ibid., p. 434.

5 Lindsay, L., 2016. Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth-Century Odyssey from America to Africa. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

6 Lindsay, L., Atlantic Bonds.

7 W. W. Colley to Charles Corey, July 13, 1881, Richmond Theological Institute Correspondence, Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

8 Garrett, C. and William T Moore, 1962. Speaking to the Mountain. Atlanta, Home Mission Board of the Southern Convention.

9 Solomon Cosby to Charles Corey, January 02, 1880, Richmond Theological Institute Correspondence, Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

10 Garrett and Moore, Speaking to the Mountain.

11 The Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), 12 August 1895; Franklin Repository (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), 10 August 1895; Jordan, L., 1930. Negro Baptist History, U. S. A. 1750-1930. Nashville: The Sunday School Publishing Board, N. B. C.

12 Jordan, L., 1901. Up the Ladder in Foreign Missions. Nashville: National Baptist Publishing Board.

13 National Baptist Convention of the United States of America. Foreign Mission Board, 19–. In Our Stead. Philadelphia, National Baptist Convention of the United States of America.

14 Scruggs, L., 1893. Women of Distinction: Remarkable in Works and Invincible in Character. Raleigh: L. A. Scruggs, Publisher.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Methodist Episcopal Church. Missionary Society, 1886. The Gospel in All Lands. New York.

18 Büttikofer, J., 2013. Travel Sketches from Liberia: Johann Büttikofer’s 19th Century Rainforest Explorations in West Africa. Netherlands: Brill.

19 W. W. Colley to Charles Corey, August 04, 1884, Richmond Theological Institute Correspondence, Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

20 Richmond Planet, 19 August 1911.

21 Richmond Planet, 9 April 1898.

22 Richmond Planet, 23 June 1894.